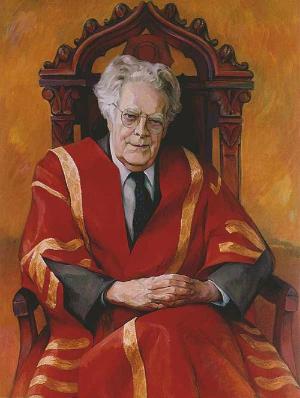

When he was still a student Frye set out to write a novel called Quiet Consummation. In 1935, he wrote to Roy Daniells:

I come up blushing shyly to confess that I am taking advantage of my unaccustomed freedom to start working a bit on a novel. Its provisional title is Quiet Consummation. It’s not much of a novel, but I want to get it out of my system. No plot or theme or thesis or anything, just yet. It’s laid out in sonata form. Amusing, I think, if it comes off at all. I am beginning to realize that while I may and probably will turn out some fairly decent things on Blake and Shakespeare and Augustine and the rest critically, the larger problem they refer back to, the relation of religion and art in symbolism, will require fictional and dramatic treatment.

In Notebook 5, which apparently dates from about this time, Frye sketched on the flyleaf, “Quiet Consummation / A Novel in Sonata Form / Eratus Howard / Part One, Exposition”; on the second leaf is an “Analysis” of the novel, outlined as the exposition, development, and recapitulation. [Frye was apparently adopting the name of his brother––Eratus Howard Frye––as a pseudonym]. He was never able to realize this fantasy. Notebook 5 contains nothing else about Quiet Consummation, and there is not so much as a whisper about it elsewhere his early notebooks. But Frye did return to it fifty years later when he was looking for a form that would combine the creative and the critical––something aphoristic, anagogic, erudite, imaginative, even fictional that would be a quiet consummation of his life’s work.

One proposal for the final book in Frye’s ogdoad, which he called Twilight, was a book of aphorisms. The desire to complete such a book emerges from a dozen or so entries in Frye’s Late Notebooks. “I wonder,” he writes, “if I could be permitted to write my Twilight book, not as evidence of my own alleged wisdom but as a ‘next time’ (Henry James) book, putting my spiritual case more forcefully yet, and addressed to still more readers” (Late Notebooks, 1:417) The reference here is to James’s The Next Time, the story of a writer whose work is admired by a small coterie but who is frustrated by his failure to reach a large audience. Frye proposes several models for his anagogic book, and he says, “I wouldn’t want to plan such a book as a dumping ground for things I can’t work in elsewhere or as a set of echoes of what I’ve said elsewhere.” “Such a book would feature,” he adds “completely uninhibited writing” and “completely uninhibited metaphor-building,” and some of the entries might even be fictional. [For Frye’s additional speculations on the anagogic book, see Late Notebooks, 1: 172–3, 238, 372.]

Toward the end of Notebook 50, when Frye realizes that he may not live much longer, he suggests still another variation on the final book. He scribbles somewhat cryptically, “Opus Perhaps Posthumous: Working Title: Quintessence of Dust. Four Essays.” And then, a dozen entries later, he adds, “Quintessence and dust; Quarks or pinpoints; Quest and Cycle: Quiet Consummation” (Late Notebooks, 415, 417). “Four Essays,” the subtitle of Anatomy of Criticism, hints at the conventions of the anatomy as a genre. “Quintessence of Dust” is a phrase from Hamlet’s dialogue with Rosenkranz and Guildenstern (act. 2, sc. 2), and of course “Quiet Consummation” (the phrase comes from Guiderius and Arviragus’s song in Cymbeline, 4.2. 280) returns us to Frye’s 1935 fantasy.

Here are a couple of the models Frye proposes for Twilight:

This may be a crazy notion, or it may be one of my central intuitions coming to a head. I’ve always wanted to write something in the conventionally “creative” modes towards the end of my life. I’ve even thought of a long poem, though I certainly know that I’d have to go through quite a metamorphosis before I could bring that off—even so, I was thinking only of the kind of versified speculation that Buckminster Fuller brought out a while ago. Fiction of course I’ve thought of more frequently, but learning the mechanics of any kind of fiction is a disheartening and unpredictable procedure at my age. So I’ve thought most frequently of a book of brief essays or meditations, perhaps a century of meditations like Traherne’s, though naturally of a very different kind. I’ve often said too (to myself) that a book like Anatole France’s Jardin d’Epicure [a bricolage of essays, dialogues, epigrams, and other short prose fragments] would be ideal in format and general conception for me, except that I’d want my book to display a less commonplace mind than his was. (Northrop Frye’s Fiction and Miscellaneous Writings, 155–6)

The interesting thing about Frye’s last-book fantasies is their correspondence to the notebooks themselves. Frye himself makes the connection between the “aphoristic book” and his “notebook obsession” (Late Notebooks, 172–3), and the notebooks are a Promethean exercise in uninhibited writing and metaphor-building. His notebooks are, of course, not Twilight, not the anagogic book of aphorisms that he dreamed about—“‘my own’ book of pensées,” as he called it (Late Notebooks, 1:372). But it is possible that the core of Twilight ould have come from a selection of his notebook entries. Frye says that Twilight is “ideally . . . a book to be put away in a drawer and have published after my death” and that he always thought of the final book in his ogdoad fantasy as “something perhaps not reached” (Late Notebooks, 1:238, 173). Perhaps his notebooks do in fact serve as the quiet consummation of his life’s work.