A footnote to Clayton Chrusch’s “The Hermeneutics of Charity,” drawn from some paragraphs on love I wrote about elsewhere.

The genuine Christianity that has survived its appalling historical record was founded on charity, and charity is invariably linked to an imaginative conception of language, whether consciously or unconsciously. Paul makes it clear that the language of charity is spiritual language, and that spiritual language is metaphorical, founded on the metaphorical paradox that we live in Christ and that Christ lives in us (The Double Vision, 17).

The various principles that are the foundation of Frye’s concept of identity (metaphor, kerygma, possession, the fourth awareness, higher consciousness) should lead us, he says, to “myths to live by.” But what are these existential myths that come from “the other side” of the imaginative? What are the “coherent lifestyles” that Frye’s hopes “will emerge from the infinite possibilities of myth”? (Words with Power, 143). Although he often appears hesitant to give a direct answer to these questions, preferring to assume the role of Moses on Mount Pisgah, the answer does surface in the conclusions of his last three books where the gospel of love becomes the focus of his discussion.

Frye’s speculations on love begin early. In Notebook 3 (1946–48) he probes the meaning of love in different contexts: his own erotic and fantasy life, his attitude toward the Church, his reflections on yoga and on time. Here are two representative reflections:

Joachim of Floris has a hint of an order of things in which the monastery takes over the church & the world. That is the expanded secular monastery I want: I want the grace of Castiglione as well as the grace of Luther, a graceful as well as a gracious God, and I want all men & women to enter the Abbey of Theleme where instead of poverty, chastity and obedience they will find richness, love and fay ce que vouldras; for what the Bodhisattva wills to do is good. (Northrop Frye’s Notebooks and Lectures on the Bible and Other Religious Texts, 17)

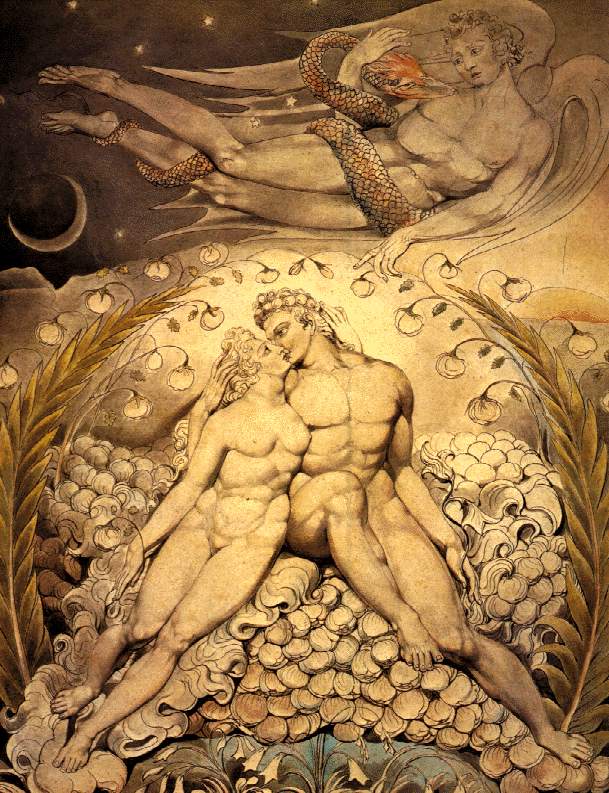

Each dimension of time breeds fear: the past, despair & hopelessness & the sense of an irrevocable too late: the present, panic & sense of a clock steadily ticking; the future, an unknown mystery gradually assuming the lineaments of the consequences of our own acts. Hope is the virtue of the past, the eternal sense that maybe next time we’ll do better. The projection of this into the future is faith, the substance of things hoped for. Love belongs to the present, & is the only force able to cast out fear. If a thing loves it is infinite, Blake said, & the act of love is itself a vision of a timeless world. (ibid., 59)

Frye’s speculations on love reappear some thirty-five years later in the conclusion of The Great Code, where he probes the meaning of the Word of God in the context of Biblical language. This language, Frye says, is enduring, inclusive, welcoming, and beyond argument, and it can move us toward freedom and beyond the anxiety structures created by the human and divine antithesis (231–2). The Great Code, however, provides little concrete guidance about the function of love in the myths we are to live by, though the notebooks for The Great Code contain numerous entries on “the rule of charity.” But during the eight years following The Great Code Frye devoted a good deal of energy to working out the implication of the language of love. In Notebook 46 (mid- to late 1980s) he writes, “Love is the only virtue there is, but like everything else connected with creativity and imagination, there is something decentralized about it. We love those closest to us, Jesus’ ‘neighbors,’ people we’re specifically connected with in charity. For those at a distance we feel rather tolerance or good will, the feeling announced at the Incarnation” (Late Notebooks, 2:696). This “only virtue” idea gets developed in Words with Power where love, Paul’s agape or caritas is said to be “the only genuine form of human society, the spiritual kingdom of Jesus” (89).