Some years ago one of Frye’s former students, Don Harron, sent me a copy of My Frye, His Blake, saying that it had been rejected by a university press because it was not academic enough. Harron’s summary of Frye’s Fearful Symmetry, however, was intended not for an academic audience but for the common reader. Harron calls his 279‑page summary a down‑sizing of Frye’s complicated and sometime difficult exposition of Blake’s prophecies. My Frye, His Blake is an abridgement of Fearful Symmetry. It is not so much an effort to simplify Frye as to make him more accessible to the nonspecialist by presenting, in Pound’s phrase, the “gists and piths” of Frye’s book––a concentrated form of its argument, combining his own summaries with Frye’s words. I’m hopeful that it might yet find a publisher.

Here’s Harron’s preface:

BEFORE BEGINNING

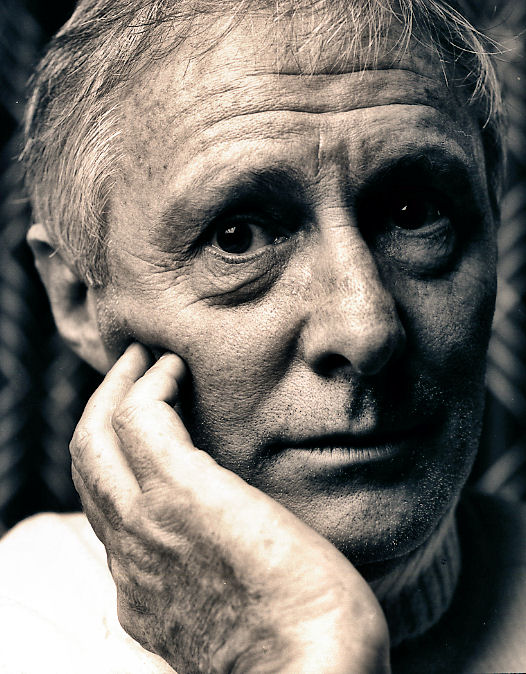

To deal first with that somewhat presumptuous and proprietary title: I am one of Northrop Frye’s former students, but can lay no special claim to him. Like James Hilton’s fictional “Mr. Chips,” he and his wife Helen remained childless throughout their lives, but bred thousands of devoted, surrogate progeny like myself, who considered them both as role models during that green island in our lives we call college days.

I was heartened by the announcement that all of Frye’s literary output is to be re-issued in a thirty‑volume collection. At the same time I worried that his legacy might be confined to academic circles, and miss the larger public he freely sought during his lifetime. This attempt of mine to summarize the first of his many books may be construed by some as a kind of Blake for Dummies, but that is not my intention.

The origin of My Frye, His Blake stems from the first essay I ever wrote for the great man back in 1946. I forget the subject of my paper, but I will never forget the mark he gave me. It was a C‑minus. He added the words: “This is mostly B.S. , but you do have a gift for making complex ideas simple.” The latter half of that cryptic statement is the reason for this book.

I was a freshman at Victoria College, University of Toronto, in 1942, but since I was enrolled in a course known as Sock and Fill (Social and Philosophical studies), I didn’t have any lectures with Northrop Frye that first year. It was months before I got to hear him in a public lecture on “Satire: Theory and Practice.” I sat beside two nuns from St. Michael’s College who rocked back and forth with delight as Frye quoted Pope and Swift and Dr. Johnson and added more than a few ripostes of his own. They nearly rolled in the aisle when he quoted Dante reaching the dead center of evil and passing through the arse of the Devil to the shores of Purgatory.

When I returned to Vic in 1945 after two years’ undistinguished service in the RCAF, it was general campus knowledge that the book Northrop Frye had been thinking about and writing for more than ten years was on the English poet and engraver William Blake (1757–1827). Fearful Symmetry is considered by many to be the most complex of Frye’s writings. It was his second book, the Anatomy of Criticism written ten years later, that gave him his international reputation as a literary critic. When I took courses with him in Spenser and Milton during my undergraduate years 1945–48, he was in the throes of preparing the Anatomy, and a good deal of that book came out in his lectures to us.

Unfortunately I never had the opportunity of taking a Blake course with Frye, but when I finished reading Fearful Symmetry, I felt that it was the most important book I had ever come across. I can still remember the sensation of the hair rising on the back of my neck as I ploughed eagerly through its pages. I hope my truncated efforts can convey some of that excitement. It is ironic that his wittily intelligent wife Helen Kemp Frye once confessed that she could never get through Fearful Symmetry. I dedicate this “down-sized” attempt to her memory.

Before I read this great book the only thing I knew about the writings of William Blake were a couple of lines from two familiar poems “Little Lamb who made thee?” and “Tyger, tyger, burning bright.” It seems I shared this knowledge with the rest of the general public. Unknown to me, and most of the rest of the world, were reams and reams of verse with the fierce savage vigor of Biblical prophecy, plus his marginal comments on the writings of other thinkers and painters, mostly of a seething ferocity.

Fearful Symmetry was published in 1947 by Princeton University Press. There was no attempt to deal in detail with William Blake’s painting or engraving, but it was a single-minded effort to bring to light some of the least read poetry in the world. It was not a Ph.D. thesis, or a “Publish or Perish” project to get to the next rung on the academic ladder: it was a personal crusade to vindicate one of the great neglected voices of English literature.

Until Frye’s treatment of Blake, most literary critics had written off this eighteenth-century poet as one of the minor pre-Romantics, the creator of a slim volume of lyrics anticipating but certainly not equaling Shelley and Byron and Keats. They had completely ignored two thirds of Blake’s output, consigning it to undeserved oblivion, and dismissing their author as a cultural hermit, a mystical snail who retreated from the harsh world of reality into the refuge of his own mind. Mystical in this sense implied “misty,” wallowing in self-contemplation and obscurantism.

To Frye, William Blake was not a mystic but a visionary––a very different species. Most mystics achieve a direct apprehension of God very few times in their lives, and only after great efforts at contemplation and relentless self-discipline, by starving themselves or sitting high on a remote rock. Not so Blake, who wrote:

I am in God’s presence night & day.

And he never turns his face away.

Many of Blake’s contemporaries thought he was completely mad. William Wordsworth was one who thought so, although he had a suspicion that if Blake had bitten Sir Walter Scott or Robert Southey it might have improved their poetry. Later, in the nineteenth century, when Romantic poets were treated like rock stars, it was felt that madness was part of artistic genius, a morbid secretion of society that could be cured homeopathically. Blake, on the other hand, considered that it was society that was mad, and not the artist. Frye came to feel that this misunderstood man demonstrated the sanity of genius, contrasted with the madness of the commonplace mind.

Everything that follows in this book is taken from Fearful Symmetry, plus a couple of updates from Frye’s remarks expressed in later years. What you read will be either Frye’s own words or a precis of them.

Bob, thanks so much for that – fascinating. So now we have a direct link from Frye to American Psycho. 🙂

Revealing an entirely new side to Canada’s comic genius. Bravo.

jb