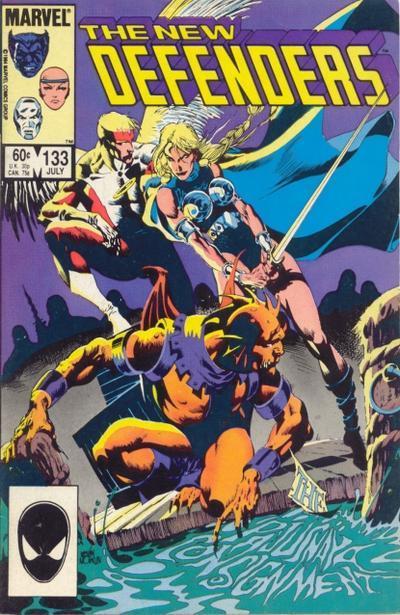

Frye appears in "The Pajusnaya Consignment" (above, July 1984) in Marvel's New Defenders series

In addition to Amis’s The Rachel Papers Frye has made his way into a number of poems, plays, novels, and discursive texts. An earlier post catalogued his appearance in contemporary poems. As for the other genres, one of the central characters of David Lodge’s Changing Places (1974) refers humorously to the perpetual motion of an elevator, “a profoundly poetic machine,” as symbolizing Frye’s theory of modes in Anatomy of Criticism (London: Seeker & Warburg, 1975; Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978), 212–13. Professor Kingfisher in Lodge’s Small World (1985), a sequel to Changing Places, is a fictionalized version of Frye. In Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water Dr. Joseph Hovaugh is modeled on Frye. Here are further examples:

• The following bit of dialogue occurs in Frederic Raphael’s play, Oxbridge Blues, from Oxbridge Blues and Other Plays for Television (London: BBC, 1984). Victor is a serious writer. Wendy is his wife:

Victor: I didn’t think you felt like discussing it.

Wendy: I don’t even know what “it” is. What is it? I know you’re ridiculously jealous of Pip and you can’t even bring yourself to accept his generosity without looking as though you’d much sooner be reading the collected works of — of — of — oh — Northrop Frye.

Victor: I would. Much. The Anatomy of Criticism, though flawed, was a seminal work in some ways. Why did you happen to choose that name?

Wendy: I wanted someone with a silly name.

Victor: I don’t find Northrop particular silly.

Wendy: Well I do. I find it very silly indeed. Not as silly as you’re being, but still very silly.

• From Gail Godwin’s The Odd Woman (New York: Knopf, 1974), 257–8:

Was Gabriel’s project quixotic? For almost two years, she had vacillated between thinking him a nearsighted fool and a farsighted genius. How could she tell? Surely there must be a way to measure it, but how? After the fact, it became a bit simpler. For instance, in the field of literature, of literary criticism, she knew Northrop Frye was a genius—even though some respectable scholars like Sonia Mark’s husband detested Northrop Frye. Frye’s ideas made sense; they rested on valuable hypotheses; they lit up the entire realm of literature for you. After you had read Frye, you thought of your favorite books as parts of a large family. You not only saw them as you had before, but you saw behind them and in front of them. It was like meeting someone, forming an opinion about this person, then being privileged to meet the person’s parents and grandparents, as well; and then being privileged to meet the person’s children, and grandchildren! Of course, someone like Max Covington would say, The person himself, alone, should be judged. What do parents have to do with it? What do his children have to do with it? They only confuse and diffuse you from the proper study of the object, which is: the object itself.

She had tried to lift her assurance about Frye—as one might gingerly try to lift an anchovy from its tin and place it, undamaged, on a plate—and transfer it toward her wavering confidence in Gabriel. Surely, during the forties and fifties when Frye was painstakingly filling his wife’s shoe boxes with notecards for Anatomy of Criticism, Mrs. Frye had had an occasional qualm. Or had she? After all, Frye had done Fearful Symmetry first. She had that to build on. She knew that her first closetful of shoeboxes had come to something. Whereas, with Gabriel, there was only the queer, eccentric little monograph, published half a lifetime ago!

• From Hazard Adams’s The Horses of Instruction (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968), 5–6.

For a day at the [MLA] convention, Jack Emory had wandered aimlessly through exhibits, mainly to glance furtively and with secret pride at the display of which his own book was a part. A study of the poets of the nineties, it represented the salvageable matter from what he now saw was a verbose, huge, disorganized doctoral dissertation. Out of idle curiosity on the first evening he had attended a meeting or two. He had heard the distinguished medieval scholar Kemp Malone speaking on “Chaucer’s Double Consonants and the Final e,” sticking it out mainly because he had studied under a man who was always mentioning Kemp Malone. The lady professor from Vassar who followed with a fifteen-minute talk about some aspect of Chaucer sent him, however, in flight to another room. There Northrop Frye, definitely an in figure, was discoursing on Finnegans Wake. Following this, his head full of quests and cycles, of mythic patterns and archetypes, and it being 11:30, he went to bed, only to dream a conversation with William Blake on the subject of Charles II.

• From Malcolm Bradbury’s Stepping Westward (London: Seeker & Warburg, 1965; Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966), 5:

In any disinterested evaluative scale of American colleges, Benedict Arnold hardly ranks tops; to [Ralph Zugsmith] Coolidge [president of Benedict Arnold College] it was more scholarly than Harvard, better built than Yale, more socially attractive than Princeton, and with better parking facilities than all of them. The student body, as it teemed about campus—very much body, the girls in their shorts, the boys in theirs—he saw from his window as young America, the best of all possible young Americans. No possible evidence of ignorance or of vice could disillusion him. Responsibility to them and to the world weighed on his head, like an over-large hat. He was totally serious; he groaned in the night; he cared and worried. He ran advertisements in the quality monthlies: “For the future! A B.A. from B.A.” He shivered when Harvard got Reisman or Toronto Frye, shivered because he saw a prospective Benedict Arnold man drawn off into false paths.

• From Robertson Davies’s “The Pit Whence Ye Are Digged” in High Spirits (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983), describing the talk at the High Table among the Senior Fellows of the “College”:

The noise of conversation was high. Two notable divines, The Reverend John Evans and The Reverend Northrop Frye, were hard at it; Dr. Evans defending the doctrine of salvation through works—the works one could grind out of others—while Dr. Frye was urging salvation through the refiner’s fire of an exacting criticism of Holy Writ.

• From “Dining Out,” a section of Maureen Howard’s autobiography Facts of Life” (Boston: Little, Brown, 1978). 78.

I remember a lunch served up in the back bedroom of a second-story faculty flat in Ohio to Northrop Frye, the literary critic, our visiting dignitary at Kenyon College. . . .I sat at the head of the table, a veritable Madame de Sévigné of central Ohio, exhausted by my labors. I cannot remember one word the great man said, yet getting up from the table I knew that I would dine out on having had him for lunch. I will not bore you with the menu which I do remember down to the last braised turnip in the grande marmite. I was charming too, always that, and knew what to ask, had “read up on,” if not read his book on Blake. Myopic and proper, bending into his soup, he talked as though we wanted really to say something. I got the impression of a generous man, so committed to his work that he could not fathom my triviality.

• From Edmund Hill, O.P., in Blackfriars 64 (February 1983): 92:

On the 17th Sunday of the year, Cycle 2, I preached, more or less extempore, on the connection between the first and third readings, respectively the story of Elisha multiplying some loves and of Jesus feeding the 5,000. To try to help the congregation bring the right frame of mind to reading the Bible I pointed out the typological connection; how behind both stories was the story of the manna in the desert, and how feeding with food is a regular biblical metaphor (or metonym—words I did not use in the sermon) for teaching the word of God. After Mass a great friend of mine said, “I disagreed with your sermon. It does matter whether things actually happened or not.” I protested that I had not said it didn’t. And then she said that during the sermon her husband had whispered to her “Northrop Frye.”

• From “The Pajusnaya Consignment,” which appeared in the July 1984 issue of The New Defenders (Marvel Comics), the villain-hissing plot is interrupted by this little entr’acte:

Frame 1

[Walking across a college campus and followed by several students is the blue-faced Hank McCoy. Coming toward them is a man, slightly stooped, carrying a briefcase. Val, the archetype of the dumb blonde, has just made a remark about Treasure Island.]

Narrator: And on that literary note we turn to the missing member of The New Defenders, Hank McCoy, a.k.a. The Beast––as he holds forth to a gaggle of undergraduates following another of his fast-becoming-infamous college lectures across the nation.

McCoy: [to the students] ––so then I thought, “Why not an Edward G. Robinson mask?”

Frame 2

McCoy: Er––excuse me for interrupting myself, but––who’s that man? He looks familiar! Prof. Frye? Professor Frye??

Student: Him? That’s Prof. Frye––dry Frye, we always call him, heh, heh––

McCoy: [doing a superman handspring and sailing through the air toward Professor Frye] ’Scuse me, folks! ––Pardon me, Professor! Pardon my boldness, but I had to speak to you!

Frame 3

Prof. Frye: Good heavens! Please––!

McCoy: Professor, I just had to tell you that your book on Blake was one of the most brilliant pieces of criticism I’ve ever read. It really enabled me to see the visionary epic form as quite distinct from the Romantic! It opened up worlds to me!

Frame 4

McCoy: I particularly appreciated the insight into the apocalyptic imagination that the events of his era generated.

Prof. Frye: Why––I believe you do understand the thrust of my inquiry, young–er, man!

Frame 5

McCoy: [walking away from students and holding on to Prof. Frye’s arm] Have you, I wonder, read Bloom’s book on Blake and revolution?

Prof. Frye: Of course! But a political approach seems almost tangential. . .

Student: [now from a distance] Gee. . .!

Another student: Who’da thunk it––maybe there’s more to Frye than we thought––?

Frye makes an appearance in still another episode of the New Defenders, “Hearts and Minds” (No. 137 [November 1984]: 17). Here, one of the gallant defenders, Iceman (A.K.A. Bobby), asks the inimitable McCoy, “Hank, what was that gibberish you said to the Wizard back there?” Whereupon, McCoy replies: “The Wizard’s a Gnostic, Bobby––I recognized his spiel from a book Professor Frye loaned me––seemed to have hit him where he lived!”* [The asterisk refers the reader to The Gnostic Religion by Hans Jonas (Boston: Beacon Press, 1963).

The author of these two episodes of The New Defenders is Peter B. Gillis. The first episode occasioned this letter to Marvel Comics from Linda Koenig of Garwood, NJ:

Dear Peter,

Peter, Peter, burning bright

In the Bullpen late at night

Introduces Northrop Frye

Into Defenders’ historye!

Seriously. . . you delighted the heart of an eternal English major and an incorrigible Blake freak.

To which the editors replied: “It’s nice to know that [Peter’s] little tribute to one of the great critical minds of the 20th century didn’t go unnoticed. It has made his day. We always knew Marvel had the most erudite readership around, and this proves it. And just wait till the Beast meets Susan Sontag.”

• From Frank Gannon, “Mmm, Manor Simulacrum: Barbecue, a Postmodern Grilling,” Harper’s (May 1989): 55–7.

The truth of the matter is you’ve got to be very careful reading about barbecue if, for example, you’ve shared a lot of baby‑back ribs and Brunswick stew with, to name one guy, Northrop Frye. That guy will wear you out. Many times I felt like calling Frye on some of his ontological assumptions, but it’s hard to get real motivated with a plate of pulled pork in front of you and a cold one in your hand. I remember a lot of great eating, lots of napkins, and plenty of cold ones with Northrop Frye.

• From Jeanette Winterson, Boating for Beginners (London: Minerva, 1990), 62, 73. Through her heroine Gloria, who tries to define herself after a male model, Winterson is satirizing Frye. At one point Gloria gets excited when she sees Frye floating by from the ark (“I read your book and it changed my life,” she yells to the receding figure).

Until her epiphany with Northrop Frye she’d been an emotional amoeba. Now . . . subject and object, herself and what she did, were very much split.

• From A Memoir of David Jones (Oxford University Press, 1981) by William Blissett, who records the following reminiscence, in which he and David Jones were discussing Conrad:

David recalled a passage . . . from one of Conrad’s prefaces. I interested him greatly by recalling an encounter that occurred one summer when I was teaching in Queen’s University in Kingston. Having rented a house, I found myself gardening under the law while an elderly gentleman next door was gardening with love. We fell into talk, and one day he asked, “Have you ever heard of a writer named Joseph Conrad?” I nodded. “He was my next‑door neighbour, in Kent. We would go for long walks from time to time and see ships making the turn between the Channel and the Thames. ‘Post,’ he would say, ‘Post, I have seen much of the world’––and he was a well‑travelled gentleman, in the merchant navy––‘I have seen much of the world but no sight to compare with that.’”

I enjoyed telling this because Mr Post’s deliberate pace and South‑of‑England speech (without the intrusive ‘eo’ sound that causes flickers of annoyance in the rest of the English speaking world) reminded me very much of David’s own style of talk. Mr Post went on to ask me if I had heard of a university professor by the name of Northrop Frye. (Yes, I wrote my thesis under the direction of a great captain of academic industry, A.S.P. Woodhouse, and a coming young man, Northrop Frye.) “Professor Frye gave a talk on the wireless, on Conrad, and mentioned a man named Ford, whose real name was Hueffer.” (Mr. Post said ‘Hoffer.’) “I wrote to him and said that we all thought, perhaps wrongly, that Hueffer was a German agent, but he wrote back to say that such was not the case, that Ford, as he called him, was a loyal Englishman though of German origin, and that anyway Conrad would never have associated himself with a German agent, and I had to agree with that.”

• Two short stories by high school students in which Frye figures as a character:

Betts, Rebecca A. “Jessie McGill.” Times & Transcript [Moncton, NB] 25 April 2009. http://timestranscript.canadaeast.com/whatever/article/645528

Wong, Jasmine. “Flight of Fancy.” Times & Transcript [Moncton, NB]. 25 April 2009. http://timestranscript.canadaeast.com/whatever/article/645527

Bob, A quibble about Frye and David Lodge (whom I have been working on recently). Lodge’s _Small World_ is self-consciously “An Academic Romance,” and Lodge used Frye’s writings on romance to help him think about the genre. But I don’t think that his Professor Kingfisher has much in common with Frye. Kingfisher, “a man whose life is a concise history of modern criticism,” is born in Vienna, and has links to Prague structuralism before coming to the USA to become a leading figure in New Criticism. All of that makes him resemble Rene Wellek, who of course wrote a history of criticism. (In other ways, the character does not correspond to Wellek.) I remember that Lodge once commented in an interview that his deconstructionist friends, who in their theorizing denied any connexion between literature and any non-linguistic reality, were the ones who were most adamant in their questions about who various characters in _Small World_ “really” were! From an archetypal point of view, the name Kingfisher signals that the character originates in Jessie Weston’s _From Ritual to Romance_ via T. S. Eliot, so the idea for the character was perhaps inspired by Frye’s theorizing of romance.

To add another title, I had the impression that in “The Rebel Angels” Robertson Davies parodies Frye’s theory of symbols from the “Anatomy,” although Frye is not mentioned by name.

I stand corrected. I should have pointed to Cherly Summerbee’s reading of Frye.

Thanks for the addition of The Rebel Angels. Not a book I’ve read, but I’ll look it up.

“The desiring self is Northrop Frye.”

Re Cheryl’s reading of Frye, that is something I had forgotten. Thanks, Bob, for reminding me of this exchange:

“You’re never telling me that those are your own ideas about romance and the sentimental novel and the desiring self?”

“The desiring self is Northrop Frye,” she admitted.

“_You_ have read Northrop _Frye_?” his voice rose in pitch like a jet engine.

“Well, not read, exactly. Somebody told me about it.” (Penguin edn. of _Small World_, p. 259).

Here’s another reference from a short story:

“Rose had, weighing on her mind, an essay on Milton’s “Il Penseroso” due for Northrop Frye and would not dare to ask such an eminent scholar for an extension for a personal reason. Troubled, she had left the Pratt library, walked in hazy winter sunlight down the snow dusty path beside the reddish stone of Victoria College and crossed the street to Ned’s coffee shop in the basement of Wymilwood.”

From Arn Bailey. Time Was The Window: A Family’s Stories, 1800-2000 (Markham, ON: Stewart Publishing, 2005). Bailey was a student of Frye, who once told his class that he had been extremely moved by “Il Penseroso” when he read it as a young person and that that experience had been influential in shaping his career in literary studies.