httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=17jymDn0W6U

Putting it all in perspective. . .

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=17jymDn0W6U

Putting it all in perspective. . .

Blake's Nebuchadnezzar

Northrop Frye letter to Roy Daniells, 20 December 1973:

It seems to me that there are two mental processes which are quite distinct, both called belief. One is the existence of evidence which seems conclusive, as when I believe that the earth goes round the sun and not vice versa. The other is a belief derived not from evidence, but from imaginative vision. A belief of this kind is an axiom of one’s conduct: what a man believes in this sense is only what his actions show that he believes. Such beliefs represent a voluntary choice from an infinite number of imaginative possibilities. The gospels present their story as a myth, an imaginative vision. They are remarkably careless about collecting or appealing to evidence in the form of testimony or reason. The account of the resurrection is designed to elicit the response “I can believe in a conquest over death achieved by human, backed by divine, power,” or something like that. I don’t think they are trying to elicit the response “I find that these things happened exactly as described, because I believe that the writers are trustworthy historians.” They are not trustworthy historians: they tell four different stories. But they are all agreed that resurrection is an important subject to decide on for belief, one way or the other. From this point of view, it is not necessarily a misleading myth to say “in Adam all die,” which simply means that everybody dies.

I agree about the habitual dishonesty of theologians, but of course they are just as confused as everyone else about the distinction between the two kinds of belief. As long as they could they tried to insist that belief in Christ was the same kind of belief as belief in the global shape of the earth. Forced out of that position, they find themselves with no standards for any other kind of belief. Very few theologians know or care much about literature or about the mental processes it calls for. So they cannot understand that the gospel writers wrote in mythical rather than historical language because they felt that what they had to say was too important to be trusted to factual language.

Northrop Frye letter to Roy Daniells, 19 March 1975

What fills me with horror and terror, to use your words, is the mystery of the corrupted human will. That is never more corrupt than when it gets to work in the religious area, in obedience to Swift’s principle that we use religion to hate each other and not for love. The desire to persecute is never founded on “believe in God,” but always on “believe in what I mean by God”––all persecution and inquisition have been products of man’s deifying of his own understanding. That and the lust for political power. In the Apocalypse of Peter, one of the earliest NT pseudepigrapha, Peter is shown hell, given a strong hint that the sufferings there may not be everlasting after all, and then cautioned not to say this to anyone when he gets back, because people won’t behave properly unless they’re threatened with this kind of bogie. That’s the way social institutions operate, and they operate in the same way even in Marxist countries where there’s no religious basis as such. They all try to paralyze man with fear.

Christianity makes a good deal of sense to me because its myth does. It identifies man and God in a way that doesn’t cripple our critical faculties, and the kind of man it sees as divine is a man who cared enough about what was happening to other men to go through a pretty grim death. I know that the Christian myth has been treated as fact but the people who did that were repeating the crucifixion when they made martyrs of people like Bruno and Servetus.

St George Killing the Dragon, Bernat Martorell, 15th century

Lecture 12. January 6, 1948

THE HERO AND THE PROPHET

A distinction exists between two types of human beings: the hero and the prophet, and the relationship between them is of primacy importance. In the hero, humanity has projected a symbol of physical man fighting the forces of the power of darkness.

The Bible contains all literary forms. It is the super-epic and it deals with the act of the hero. One of the key ideas is the struggle, with nature or with other men who symbolize the forces of nature. The development is the great archetype of the hero’s struggle with darkness, such as the dragon, and the victory of light over darkness at every sunrise. The solar symbolism here is exhaustive.

The Bible centres on a single heroic act: the struggle with darkness and the resultant victory. In medieval sculpture Jesus is pictured as dragon killer.

The hero, or king, is not fully conscious of what he is doing. The hero is illusive, inscrutable, and therefore commands loyalty. Christ as the suffering hero has that illusive quality. There is a feeling of the distant hero who proceeds to inevitable fate and triumph in the “heroic” Christ who says “touch me not.” The hero is too preoccupied with his action to know what he is doing, like Achilles brooding in his tent. The heroes are figures moving in a ritual, not in the myth, and they move with a silent and unconscious quality.

The other type is the prophet who, in a sense, is the opposite. He has the disinterested view of humanity, and yet is articulate. He is not known for physical perfectibility and is likely to be stunted or deformed. He is the observer, the watcher, which the king is not. The man who is both hero and prophet is such a schizophrenic that he can’t do anything.

The hero and the prophet are different. The hero is the actor, the prophet is the articulate person who explains the myth. The poet, then, is the prophet.

The hero is the centre of activity; the prophet is the circumference of activity—the whole range of experience is in his mind. The hero is always “somebody else,” while the prophet is identical with ourselves because we have to go into his mind and make contact. All through humanity, in practise the hero and the prophet are separate. But ideally they are the same. The hero’s inscrutability is because he knows what is going on. The prophet must be able to practice what he preaches.

The priest is the intermediary, neither prophet nor hero. He stands at the point at which the ritual and myth converge. The hero still triumphs but he will be killed. The prophet will become articulate but never causes. The poet who enters the social causal sequence contaminates himself. It is the priest who understands the myth and who performs the ritual. The thing done and the reason for it are understood by the priest. Continue reading

No sooner had I put up the previous post announcing the latest additions to the Denham Library than I discovered a mysterious gift stuffed into my stocking hung by the chimney with care — okay, it was actually an email with an attachment from Bob, but still no less amazing. In it was a 162 page previously unpublished Frye manuscript, “Notes on Romance,” which I have breathlessly just added to the library (once again, see that new link in the upper right hand corner of our Menu column). After the holidays I will have to speak to our tech adviser at McMaster’s Mills Library, the wonderful Amanda Etches-Johnson, about putting such a lengthy text into a more manageable format, such as PDF, but I could not resist sharing it with you all on the longest night of the year.

God bless us, every one!

We have added to the Denham Library transcriptions of class notes provided to Bob over the years by former students of Frye. (See the Robert D. Denham Library link in the top right of our Menu column.) While transcribing Frye’s diaries Bob corresponded with more than a hundred students who are mentioned in them. His immediate purpose was to gather information for annotating passages in the diaries. But he also asked correspondents to comment on Frye as a person and a teacher, as well as the scene at Victoria College during the 1940s and 50s. The correspondents responded generously, and eighty-nine of their reminiscences have been brought together in a manuscript Bob is working on, Remembering Northrop Frye: Recollections by His Students and Others in the 1940s and 1950s. Several of the correspondents also offered to send their class notes, which Bob continues to transcribe and which we will post in the library as they become available. These are treasures, including class notes from Frye’s famous Religious Knowledge course, 1947-48, which we will also continue to post on the blog one lecture at a time.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S-5ar30_tgg

“Jingle Bells” from India

Andrew Sullivan’s blog, The Daily Dish, is running an ongoing series of “Depressing Christmas Songs” — which, interestingly enough, has strong Canadian representation, thanks to Joni Mitchell, Stan Rogers, and Sarah McLachlan.

In keeping with Russell Perkin’s newly published article in the Journal (see the live link at the upper right corner of our Menu column), here are some truly out-of-the-way Christmas songs that are appropriate to the winter solstice, which is today.

Below are the four complete Christmas editorials Russell Perkin refers to in his article, “Northrop Frye on Christmas,” newly posted in our Journal (see the live link in the upper right hand corner of our Widgets menu).

MERRY CHRISTMAS (I)

December 1946

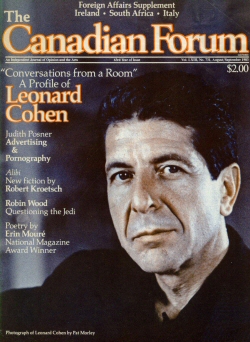

Canadian Forum, 26 (December 1946): 195. Reprinted in RW, 378–9, and in Northrop Frye on Religion.

Christmas is far, far older than Christianity, as even the pre-Christian Yule and Saturnalia were late developments of it, and it was never completely assimilated to the Christian faith. Our very complaints about the hypocritical commercializing of the Christmas spirit prove that, for they show how vigorously Christmas can flourish without the smallest admixture of anything that could reasonably be called Christian. Christmas is the tribute man pays to the winter solstice, and perhaps to something in himself of which the winter solstice reminds him. We turn on all our lights, and stuff ourselves, and exchange presents, because our ancestors in the forest, watching the sun grow fainter until it was a cold weak light unable to bring any more life from the earth, chose the shortest day of the year to defy an almost triumphant darkness and declare their loyalty to an almost beaten sun. We have learned that we do not need to worry about the sun, and that there is no monster big enough to swallow it. We have yet to learn that no atomic bomb will ever destroy the human race, that no Dark Age will (as it never has done) totally overspread the earth, that no matter how often man is knocked down, he will always pick himself up, punch drunk and sick and morbidly aware of his open guard, spit out some more teeth, and start slugging again. At that point there is a division between those for whom Christmas is a religious festival, and for whom the new light coming into the world must be divine as well as human if the struggle is ever to be won, and those for whom the festival is human and natural and points to an ultimate human triumph. With this difference in outlook the Canadian Forum has nothing to do, but to all of its readers who recognize the primary meaning of Christmas, and who realize that generosity and hospitality and the sharing of goods make a better world than misery and persecution and the cutting of throats, it wishes a Merry Christmas.

MERRY CHRISTMAS?

December 1947

Canadian Forum, 27 (December 1947): 195. Reprinted in RW, 380–1, and in Northrop Frye on Religion.

A passage in the Christmas Carol describes how Scrooge saw the air filled with fettered spirits, whose punishment it was to see the misery of others and to be unable to help. One hardly needs to be a ghost to be in their position, and as we light the fires for our Christmas they throw into the cold and darkness outside the wavering shadows of ourselves, unable to break the deadlock of the U.N., unable to stop the slaughter in China or India or the terror in Palestine, unable to release the victims of tyrannies still undestroyed, unable to deflect the hysterical panic urging us to war again, unable to do anything for the vast numbers who will starve and freeze this winter, and above all unable to break the spell of malignant fear that holds the world in its grip. Yet Dickens’ ghosts were punished for having denied Christmas, and we can offset our helplessness by affirming Christmas, by returning once more to the symbol of what human life should be, a society raised by kindliness into a community of continuous joy.

Because the winter solstice festival is not confined to Christianity, it represents something that Christians and non-Christians can affirm in common. Christmas reminds us, whether we put the symbol into religious terms or secular ones, that there is now in the world a power of life which is both the perfect form of human effort and all we know of God, and which it is our privilege to work with as it spreads from race to race, from nation to nation, from class to class, until there is no one shut out from the great invisible communion of the Christmas feast. Then the wish of a Merry Christmas, which we now extend to all our readers, will become, like the wish of a fairy tale, a worker of miracles.

Here is a recent comment from Glenna Sloan:

Frye and Bloom? It would never occur to me to consider them together. My interest in Frye’s work is pragmatic and begins with the Anatomy and other writings. The interest centers on his views on education which are immensely important to me and have been the basis of graduate courses in education that I have developed and taught at Queens College, CUNY for decades. At the Frye symposium in Ottawa in 2007 we heard papers about Frye and Bakhtin, Frye in relation to other scholars. Provacative, perhaps. But Frye is in a class by himself. Let’s have more comment on what he had to say.

Earlier posts on this blog have recommended or suggested just the opposite of what Glenna is saying here: that we have to bring Frye into dialogue with current criticism and theory if he is to be made relevant again. But the term relevance simply means trendy, the idea that Frye’s thought can only be vindicated by its relevance to contemporary concerns. So I tend to be very much of Glenna’s school of thought. It is in fact easy to make Frye relevant to contemporary concerns, since his theory of literature and culture already includes them as modes of criticism and theory that have–to use a trendy term–”always already” been there. Much of contemporary criticism and theory are just recurrences of the same old fallacies. That is why the polemical introduction to Anatomy of Criticism has never dated: the only thing that has changed are the proper names. Literary and cultural criticism keeps looking outside itself for inspiration, and we end up with a host of historians, sociologists, and psychologists manqués masquerading as literary critics and scholars.

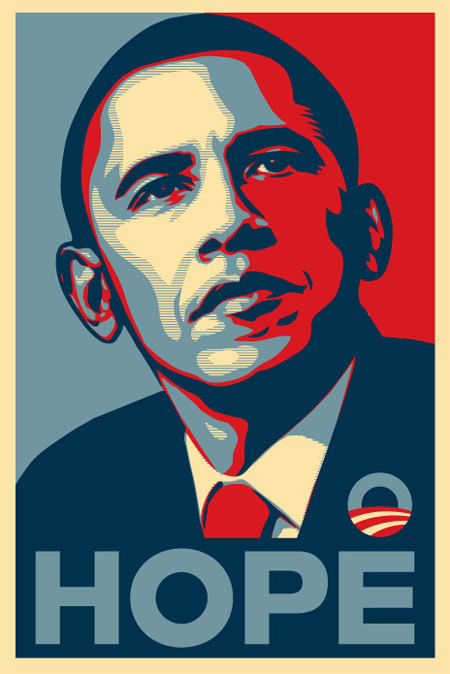

In a similar way, Frye always astonishes me by the way in which he has so much to say about current events today. Here, for example, is Frye on Obama:

One diachronic illusion is the democratic election ritual: the pretence that the new leader will begin afresh. Actually, every leader inherits a situation; almost everything he can do is prescribed for him. The head of a great power, like the President of the U.S., has a considerable potential power of destruction, but relatively little chance for creativity or innovation. Again, many things are technologically feasible which will not be done without a sufficiently powerful economic or political compulsion to do them: hence the sense of science-fiction unreality in so many gazes into the future. (para. 359, Notebook 12; CW 9: 219)

Russell Perkin has posted an article in our brand spankin’ new journal: “Northrop Frye on the Meaning of Christmas”. To see it, simply hit the live link in the Journal widget at the top right of our menu column.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a0XjRivGfiw

Continuing with Frye’s “The Great Charlie” (original post here).

Frye’s reading of Modern Times is compelling enough to cite it in its entirety:

Since Mark Twain, no anarchist of the full nineteenth-century size has emerged since Charlie Chaplin… For all its plethora of revolutionary symbols, Modern Times is not a socialist picture but an anarchist one: an allegory of the impartial destructiveness of humour. Put into the perfectly synchronizing machinery of a factory, a jail, a restaurant, this forlorn and willing Charlie wrecks all three, not by trying to but by trying not to. He very nearly accepts the highbrow’s compromise with society by singing a song no one understands and dares not admit ignorance of, but even this does not work. He gets, however, an insight into love, courage, and sacrifice with the foremen who bully him and the cops who beat him up no more understand the nature of than a bedbug understands the nature of a bed. We are left with a feeling that the man who is really part of his social group is only half a man, and we are taken back to the primitive belief, far older than Isaiah or Plato but accepted by both, that the lunatic is especially favored by God. (Northrop Frye on Modern Culture, 100-1)

The first part of the movie appears above. The rest of it after the jump.