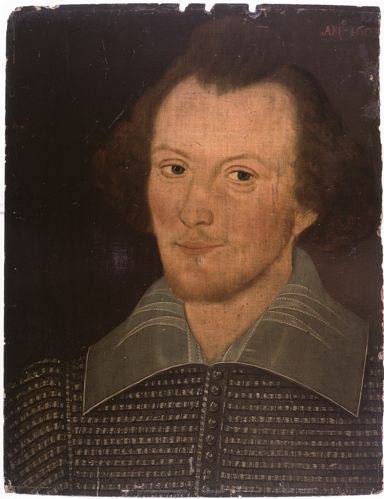

The “Sanders portrait,” the “Canadian” Shakespeare unveiled in 2001, purportedly painted from life in 1603.

Russell’s post on Greene and Shakespeare raises a number of questions about the relation between literature and ideology — a subject that has always been at the centre of literary criticism and shows no sign of going away.

Frye, in a display of irreverence as cheeky as Greene’s, famously observed (referring both to the relatively thin biography and the posthumously published Droeshout portrait) that we have very little hard data about Shakespeare: a few signatures, a handful of addresses, “and the portrait of a man who is clearly an idiot.” As Russell points out, Frye is always able to make a distinction between the “man” (who may possess idiotic personal qualities and even more idiotic ideological views) and the “writer.” For current critical theory and practice, this must seem an indefensible position. How is it possible for anyone to produce work independent of their all-encompassing social conditioning and the prejudices it spawns?

For Frye, the answer begins with the fact that literature possesses both “autonomy” and an “authority” unique to it. Literary archetypes — whose universality can be discerned by the widest possible inductive survey of literature throughout history and across cultures — are expressive of imaginative constants and primary existential concerns. Moreover, the context is fundamentally different. Language in its everyday social function is “work”: expressing beliefs, necessities, truths, and so on. Literary structures, on the other hand, are, in their imaginatively recreational function, “play”: they “exist for their own sake” and provide no requirement of belief or claim to truth. Ideology, in short, compels; literature invites. And upon that distinction everything follows, including the fact that the writer (like, say, T.S. Eliot, about whom Frye directly addresses this very issue) may be consciously pushing a personal ideological agenda from which the literature itself displays a stubbornly independent purpose. This is why literature is potentially “visionary”: it provides us with a clarified sense of what we want and who we would like to be without providing any compulsory program of action or belief. Literature as recreation merely provides the opportunity for re-creation; it does not and cannot compel it. What we choose to do in response to the existentially concerned but still aesthetic experience of literature is always entirely up to us, including (as we know all too well) doing absolutely nothing at all.

Frye more or less takes up these issues in the opening pages of the Introduction to On Shakespeare. In fact, here is the complete second paragraph of that Introduction:

We have to keep the historical Shakespeare always present in our minds to prevent us from trying to kidnap him into our own cultural orbit, which is different from but quite as narrow as that of Shakespeare’s first audiences. For instance, we get obsessed by the notion of using words to manipulate people and events, of the importance of saying things. If we were Shakespeare, we may feel, we wouldn’t write an anti-Semitic play like The Merchant of Venice, or a sexist play like The Taming of the Shrew, or a knockabout farce like The Merry Wives of Windsor, or a brutal melodrama like Titus Andronicus. That is, we’d have used the drama for higher and nobler purposes. One of the first points to get clear about Shakespeare is that he didn’t use the drama for anything: he entered into its conditions as they were then, and accepted them totally. That fact has everything to do with his rank as a poet now. (On Shakespeare, 1-2)

So what does Shakespeare’s “rank as a poet” really amount to? It may be summed up by the fact that he does not ever subordinate the autonomy and authority of his art to any external consideration: “all the world’s a stage” is not just a clever conceit in Shakespeare, it is a radical metaphor of his imaginative worldview. As Frye puts it, “In every play Shakespeare wrote, the hero or central character is the theatre itself” (OS 4). He may reflect the beliefs, biases, anxieties and prejudices of his time in a way his audience might recognize and even approve of, but he doesn’t promote them. The Merchant of Venice is nowhere close to reducible to the anti-Semitism it conjures; The Taming of the Shrew overturns the complacent sexism it renders; The Merry Wives of Windsor unexpectedly offers up a more egalitarian and tolerant vision of society once the knockabout farce has played itself out; and Titus Andronicus proves to be a powerful meditation upon the grisly absurdity of the human capacity for cruelty. Why? Because Shakespeare allows his plays to play without ever feeling the necessity of putting them to work in the name of some ideology, however noble or well-intentioned it may otherwise claim to be.

Michael, I went back to the Introduction to _Northrop Frye on Shakespeare_ and found some ambiguities I’d like to explore further. On the one hand, as you eloquently assert, Frye emphasizes that Shakespeare’s plays transcend the time and place of their origin. On the other hand, Frye says that “We have to keep the historical Shakespeare always in our minds” in order to avoid thinking of him as only “our contemporary,” as Jan Kott put it in his 1964 book _Shakespeare Our Contemporary_, a book I read avidly as an undergraduate.

Frye says that we have no idea what Shakespeare’s political or religious views were, and that his plays merely take elements of the social life of the time and use them as material for the creation of his theatrical world. And yet, at the same time, with the sureness of touch that made him such a superlative teacher, Frye selects various examples from the plays to illustrate to his students, and readers, how different Shakespeare’s world was from ours. In suggesting that _Macbeth_ was written with James I in mind, he comments that “Shakespeare seems to have had the instincts of a born courtier,” and he refers to the way that _Sir Thomas More_ was seen as politically subversive, while a revival of _Richard II_ sought to promote the cause of the Essex rebellion. In other words, Frye hints at the kinds of connections which dominate the criticism of Stephen Greenblatt and other new historicists. And why not? The _Richard II_ anecdote is a tantalizing fact.

The truth is that we want to know what Shakespeare was like, and whether he was a Catholic sympathizer or not, and even what he looked like. (Today in the Globe and Mail there is an article about how Emilia Lanier has been offered as the latest anti-Stratfordian pretender to the claim of authorship of the works of the Bard). The popular fascination with the pictures purporting to be of Shakespeare – with which you have effectively illustrated the blog on two occasions – is another sign of our interest in Shakespeare the man. It’s an interesting parallel that a litle while ago there was a controversy about a portrait supposedly of Jane Austen, of whom there are only certainly the sketches by her sister Cassandra.

My point is simply that it seems to me legitimate to wonder what Shakespeare is doing with his historically resonant references to Catholicism or to the deposing of monarchs, even though we can never know for certain. And even Frye, in spite of his avowed interest in the plays as theatrical art and his assertion that we know almost nothing about Shakespeare, is moved to the conjecture that Shakespeare had the instincts of a born courtier. That’s an interesting supposition, and one that could no doubt be developed at length, perhaps even in a way that might illuminate some aspects of the plays.

Hi, Russell. I admit that I take a hard line on the distinction between literature and ideology because it seems to be at the heart of Frye’s thinking, and it is for me at least one of the most compelling aspects of his criticism as a whole. It’s not that literature doesn’t reference ideology — and certainly not that writers lack ideological convictions of their own — but rather that literature exceeds ideology by way of imaginative archetypes that express universal human concerns. I am pretty sure this is what Frye means when he talks about literature’s “autonomy” and “authority”; an authority, again, that unlike ideology does not compel but invites. It certainly accounts for literature’s ability to communicate across cultures and through history: its ideological reference is incidental rather than fundamental.

You’re right that Frye says we must keep the “historical Shakespeare in mind,” but that is to prevent us from kidnapping him “into our own cultural orbit.” Having avoided that pitfall, we are freer to appreciate the cross-cultural and trans-historical considerations that literature provides. It is why Frye at various times says that literature is both “the language of love” and “the charter of our freedom.”

Maybe I can illustrate this by referring to my own convictions about Shakespeare the man rather than Shakespeare the writer. I am confident, for example, that Shakespeare (on what seems to be the best available evidence) came from a recusant Catholic background. I could elaborate on the reasons for this, but in the end it wouldn’t make much difference because ultimately the plays are independent of any proofs that may be offered either way. Appreciating the historical Catholic references in the plays may add resonance to our experience of them, but our total imaginative experience of the plays is not defined by ideological allusions, whatever their source might be. If it were otherwise, then Shakespeare would be a “Catholic” writer rather than an artist acclaimed throughout the non-Catholic world.

You’re right that we all have an unquenchable curiosity about “the man Shakespeare,” but that is because we retain some notion that the “biography” might yield some key to what the literature “really means.” But literature “means” according to its literary reference — which is imaginative — and not to anything external to it. Frye’s point, as I understand it, is that we should not read literature ideologically but that we should read ideology literarily because all language is metaphorical, and all metaphor is an imaginative construct expressive of human concern. Ideology is, as he makes clear in Words with Power, a secondary derivation of primary concern, and, because it is secondary, it is not essential to our experience or understanding of literature as literature.

Thanks, Michael. Just a quick follow-up question, in the half-time of the Cardinals-Saints game: do you agree that Shakespeare had the instincts of a born courtier?

Laughing! Yes, Russell, I guess I do. The evidence seems to be his ability to render the manner to which he was not born. Does that make a difference? If Shakespeare was from a recusant Catholic family (his father withdrawing from public life not because of finances but faith), then his ability to negotiate the perilous politics he encountered in London while still a young man from the provinces is truly remarkable. But doesn’t that mean that his integrity as an artist, even in such a poisonous environment, very quickly took precedence over his suspect status as a Catholic?