I’ve been mulling over Clayton’s comment about Frye’s antisupernatruralism. There are close to a hundred places in Frye’s writings where he uses the word “supernatural,” but I don’t get the sense from these references that he’s antisupernatural. Most often Frye’s use of “supernatural” does not point to some transcendent religious realm or being. For him, the supernatural is what is fantastic (ghosts, vampires, omens, portents, oracles, magic, witchcraft, and the like) or above nature––as in the heroes of myth in the Anatomy: superior to other people (superhuman) and to their environment (supernatural). The supernatural would include the “children of nature” (“the helpful fairy, the grateful dead man, the wonderful servant who has just the abilities the hero needs in a crisis,” Anatomy 196–7) that we find in folk tales and romances. For Frye the supernatural is not a term that is opposed to unbelief. It’s simply the antithesis of the natural. In his essay on Emily Dickinson he writes, “the supernatural is only the natural disclosed: the charms of the heaven in the bush are superseded by the heaven in the hand.” Sometimes Frye speaks of the supernatural as phenomena that are difficult to explain. He reports on this episode with his mother:

She has always regarded her mind as something passive, worked on by external supernatural forces, and is very unwilling to think that anything might be a creation of her own mind—besides, it flatters her spiritual pride to think of herself as a kind of Armageddon. She told me that once she was working in her kitchen when a voice said to her “Don’t touch the stove!” So she jumped back from it, and something caught her and flung her against the table. Half an hour later the voice came again, “Don’t touch the stove!” She jumped back again and this time was thrown violently on the floor. When Dad came home for dinner he found her with a black eye and a bruised shin. I have read a story by Thomas Mann in which he tells of seeing a similar thing in a spiritualistic séance [the episode involving Ellen Brand toward the end of Mann’s Magic Mountain—the section entitled “Highly Questionable” in chapter 7]: that story was the basis of the priest’s remark to the ghost in my Acta Victoriana sketch: “If you are very lucky, you may get a chance to beat up a medium or two” [“The Ghost”]. Mother has also heard noises like tapping and so on, and was tickled to get hold of a copy of a Reader’s Digest in which a writer describes having gone through exactly similar experiences [Louis E. Bisch, “Am I Losing My Mind?” Reader’s Digest, 27 (November 1935), 10–14.] The best way to deal with mother is, I think, to get her books telling of similar things that have happened to other people: she’s not crazy, but might be excused for thinking she was if she didn’t realize that such things are more common than she imagines. She was delighted with my Acta story, and I’ll try to get her that Mann thing and C.E.M. Joad’s Guide to Modern Thought, which has a chapter on those phenomena. (Frye-Kemp Correspondence, 13 August 1936).

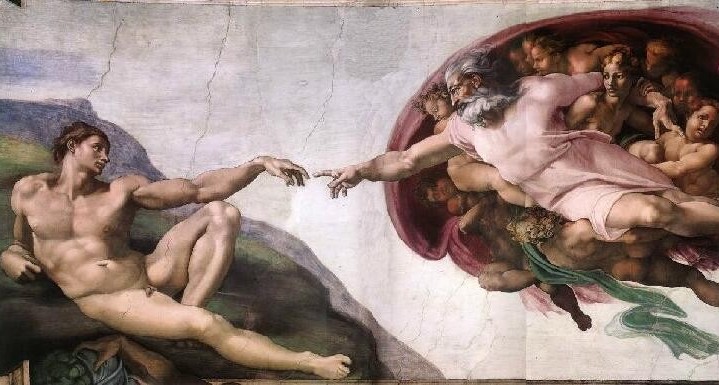

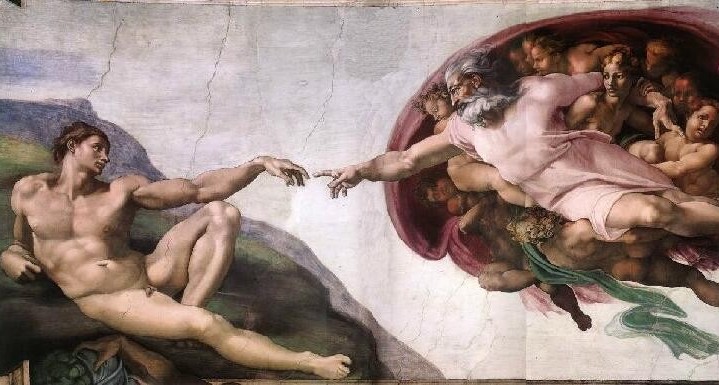

In Fearful Symmetry Frye speaks of the supernatural as the human creative power: “All works of civilization, all the improvements and modifications of the state of nature that man has made, prove that man’s creative power is literally supernatural. It is precisely because man is superior to nature that he is so miserable in a state of nature” (41). Frye’s reaction to natural religion, with its premise of the analogia entis [anology of being], is almost always negative. Both Word and Spirit, he declares in his Late Notebooks, can be used without any sense of the supernatural attached to them.

Continue reading →