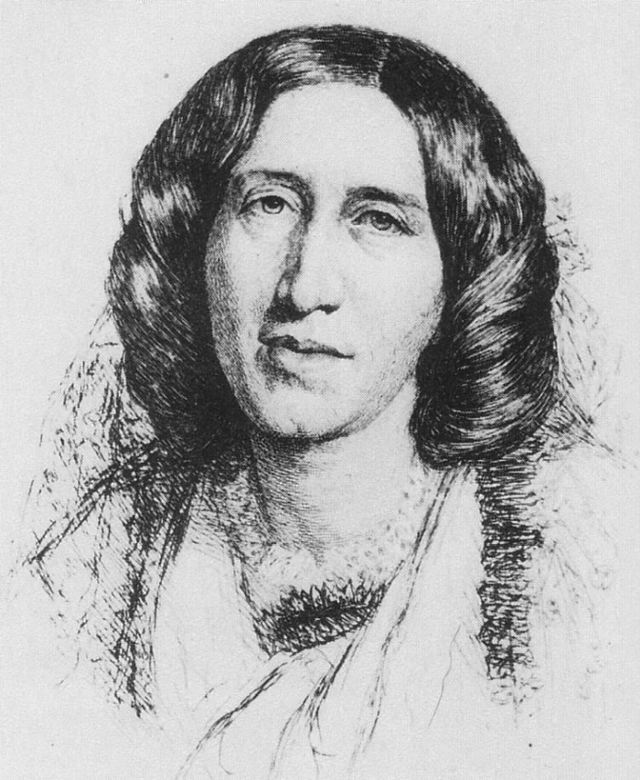

Joe Adamson notes that the “double-heroine” structure is worthy of further study whether it be (and I hope I am not over-reading here) in canonical literature or in popular literature. In his response to my post, he mentions one of my favourite novels, Daniel Deronda by George Eliot. The novel itself was added to my field exam bibliography late in the process, and I remember groaning when it happened (and also questioning why a realist novelist was to be included). However, as I started to read the novel, I quickly became entranced by it and ended up getting through it in a single day. But, after thinking about Joe’s response, I’d have to say our readings are different.

It seems to me that Daniel Deronda’s selection of Mirah isn’t that he selects the “dark Jewish heroine” as a rebellious move, but rather that the choice is, in many ways, a reinscription of Frye’s structure of romance. The great “surprise” of Daniel Deronda is the protangonist’s realization that he is Jewish and not Christian. His marrying Mirah is really, I think, quite similar to Ivanhoe – although in Eliot’s novel, what has been reversed or inverted is not structural, but religious. That is, the structure of the marriage hasn’t been disrupted nor has the definition of community – if anything, Deronda is the sort of pharmakos character (rather than hero) who must be accepted by the Jewish community.

Daniel Deronda is, because of the problems of religion and genre, fascinating, especially in light of Frye’s writings on genre. The “problem” with the novel – if there is a problem – is that it is two novels. Many critics have pointed this out; F.R. Leavis, for instance, memorably suggests that the Jewish novel should be edited out and readers left with the Christian novel named, Gwendolen Harleth. Of course, the opposite argument has been made as well. In a recent article, “Writing the Philosemitic Novel: Daniel Deronda Revisted” (Prooftexts 28, 2008), Alan T. Levenson writes: “[i]f gentile readers preferred Gwendolyn to Daniel on literary grounds, and Jewish readers preferred Daniel to Gwendolyn on political grounds, all agreed that the novel intended to champion Jewry—a perspective, which, as we shall see, has been challenged in more recent criticism” (130).

But this “double novel” with its “double heroines” also includes a hero who serves a “double” purpose (if not more). Deronda acts as the conduit between the two novels and is able to take on the role of hero of tragedy – for Gwendolen’s story is tragic – and hero of romance – Deronda’s story proper. Eliot’s “genius” is that she is able to weave these two narratives together and allow readers to “identify with characters.” Frye, in his notebooks on romance, observes that “[i]dentifying ourselves with a character we like is the first step towards genuine identity. The next identification is with the social group presented, identifying in the sense of participation” (CW XV:237). The challenge – which really marks Eliot’s “genius” – is that she presents a hero with whom many identify, but then this identification is suddenly disrupted by the realization that Deronda is Jewish. That is, we move from the archetypal hero to the “dark hero” character. How then does one’s identification with a character change when the narrative includes such a religious and radical change? Frye goes on to say that, “[t]hen we move to realizing that romance, with all its snobbery, deals with projections of ourselves, not with the divine being out of reach. Somewhere in here goes the final renunciation of social mythology and the turn toward genuine literature” (CW XV:237). I am not sure that I fully understand the idea of a “genuine literature” (it sounds strangely and uncomfortably Bloomian), but Eliot’s Daniel Deronda certainly seems to draw upon these ideas, at least in my own reading of it.

In many regards, Deronda becomes like the “double heroine,” but he embodies both heroines (and of course is the hero rather than heroines – although, like heroines, he is virginal). He is the hero of Gwendolen’s story and also of Mirah’s story. However, he only fulfills the requirements of the romantic hero in one of these stories and readers are left to come to terms with this heroism and ultimately to decide if they are satisfied with Eliot’s choices. It would, however, seem that Eliot has managed to bring, as Joe puts it, the “the two cadences or ‘creative moods’ of romance, the comic and the tragic or romantic, the social and the withdrawn, the world of ritual and the world of dream,” together in the character of Deronda.

All of this being said, I was introduced to the novel as a Comparatist who is in fact a Hispanist. English literature is a foreign literature in my research.