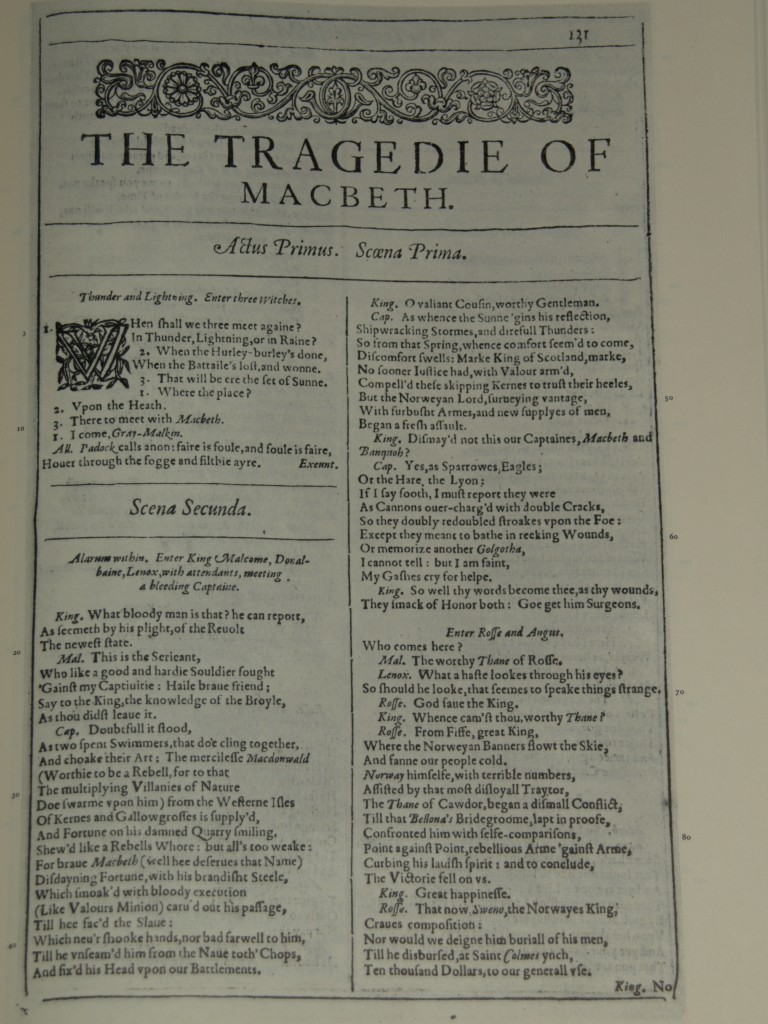

Macbeth, First Folio, 1623

Lecture 16. February 3, 1948

ELEMENTS OF TRAGEDY

Aristotle’s catharsis means that the audience is not to have pity or fear. The correct response is: the hero is a man suffering from the tragic flaw; how very like things are. The Greek idea of fate was not external; it is the way things always happen. The law of human life is not moral, but a law nevertheless.

Tragedy is a kind of implicit comedy. It is the full statement of which comedy gives only a part. The complete story of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion is a comedy. The implicit resurrection gives balance and serenity. Tragedy completes itself as comedy. The story of Christ has no ultimate tragedy. Death is a tragedy, but there is resurrection here.

In other tragedies the hero dies on stage and he revives in the mind of the audience. Tragedy is the development of the ritual of sacrifice. The typical act is the death of the central figure, the king or prince in whose death the people find life. Aristotle’s catharsis is not a moral quality. It casts out pity and fear, which are moral good and moral evil.

To say that Macbeth is a bad man is the reaction of terror, of moral evil. Sympathy with him on the grounds of fate, his wife’s influence, etc., is pity: moral sympathy with the hero. The real function of tragedy gets beyond moral reaction. The point is not whether Macbeth was good or bad. Tragedy goes beyond that. The catharsis in the audience is that the dead man on the stage is alive in them. The audience is united in the death of the hero. Modern tragedies are moral in that they stimulate sympathy or condemnation. Shaw’s St. Joan is moral. In King Lear, though, his death is a release. He attempted to find divinity in his kingship and failed. He found it in suffering humanity.

From the spectator’s point of view, Job is funny. The watcher is released from the action and his perspective, therefore, is one of comedy. Tragedy has the reversal of perspective. Tragedy is a work of art seen from the spectator’s point of view as entertainment. Hamlet asks to be written up: Othello, the same. Tragedy has a point when limited in art form and seen by an audience.

The audience’s perspective is comic because they are the watchers. The tragic hero is unaware of the humiliation of being watched. Lear is mercifully unaware of this when scampering around the stage mad. Hamlet feels that all eyes are upon him. He feels this to such a point that he takes it out on Ophelia. He kills Polonius because he is being watched. In Aeschylus’ Prometheus, he is stretched out on a rock. He speaks first so that people won’t stare at him. He says, “Behold the spectacle.”

Job sees God as an inscrutable watcher. In Chapter 7. he describes his fallen state––no sense in what happens––if there is a God who doesn’t interfere, then he is merely the watcher, and this is unbearable to Job. Verse 11: “Am I a sea or a whale that thou settest a watch over me?” Verse 8: “The eye of him that hath seen me shall see me no more; thine eyes are upon me and I am not.” A sense of loneliness, but of being watched.

Othello’s black skin means that all eyes are drawn to him. Here, it is subtler. The comforters are not making fun of Job. But sympathy is harder to put up with then ridicule. Job knows God acts — but why this way? It worries Job.

COMEDY INHERENT IN TRAGEDY

The audience is imaginatively detached from the tragedy: this isn’t happening to me. This enables the audience to get rid of pity and terror. When you are detached, you let the whole stream go before you. Comedy is inherent in tragedy because the hero is separate from the people who are watching him. Shakespeare has some grotesque, horrible comedy. The Fool and Edgar and the madness in Lear contribute to a horrible comedy. In Othello, there is the sense of a comical situation that twists the neck of tragedy. Yet, they are a part of the fact that comedy binds up the wounds of tragedy.

Job is not a tragic hero in the Shakespearean sense. The hero always has an aura of divinity, a man marked for this. Job’s point is that he is not a special figure, but an ordinary observer of the law. Lear must go through more than Job because he has to fight his way out of kingship. Hamlet won’t compromise and follows through the pattern of not submitting to the powers of darkness even when they are disguised as his own father.

The tension in Job is that of a Platonic dialogue rather than tragedy on the stage. Tragedy presents a sense of lost direction; the hero never knows why he suffers. Job finds out. In Greek tragedy there is the deus ex machina. In Jewish law, it is the deus in machina, the machine of rites and ceremonies. From the fulfillment of the law comes the highest good of man, but the progression of ceremony and rites can mechanize life.

God operates this “machinery” of the world. In Job, God withdraws the machinery from the world. It is because Job refuses to let God withdraw that something eventually happens to him.

The effect of the prologue is to detach God from the moral and natural law. He is the watcher, not the ordaining, God. Job is thrown into a desert world where the law doesn’t operate. The Jewish idea of deus in machina means “do this and you get your apple”: bribe and reward, happiness is the inevitable result of virtue, and so on, because God is the First Cause, etcetera, etcetera. Then God withdraws and the rain falls on the just and the unjust––the evil prosper and the good man gets it in the neck. Job is forced to outgrow a God that causes things. Job knows that, and therefore he won’t listen to the comforters.

We feel that God has played Job a dirty trick, and Job feels it, too. He doesn’t defy God; he curses the day he was born. Job is not given a chance to strike a pose or to look dignified; he is too busy scratching himself. Greek heroes suffer in dignity. The thing that permits dignity is the act of dying. But God spares Job’s life.

You can never work out a consoling formula about the Book of Job. Tragedy ignores moral order. The feeling exists that Job is in the Bible and therefore must be reassuring and respectable. The same idea is in A.C. Bradley’s critical work on Shakespeare: in spite of all the horrid tragedies, Shakespeare was a good guy at heart and believes in a moral force governing the world. All you have to do is to read the plays to see how completely that theory is blasted.

Here is God creating hell, and letting it happen in a way that creates the least sympathy for him. It resolves into the fact that there is no point in moral arguments at all.