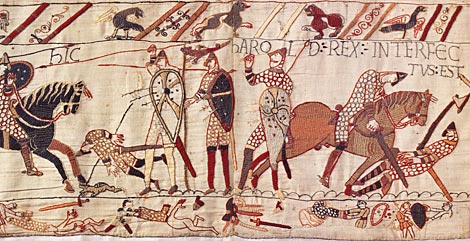

Death of Harold (centre), Bayeux Tapestry

On this date in 1066 William the Conqueror defeated Harold II in the Battle of Hastings to become King of England.

Okay, yes, it’s a stretch — and the reference is only incidental — but I’ll use any excuse to cite Frye where he is most accessible on the unique authority of literature. And it’s remarkable, isn’t it, how often we come across extraordinarily lucid passages like this one from The Educated Imagination:

We can understand though how the poet got his reputation as a kind of licensed liar. The word poet itself means liar in some languages, and the words we use in literary criticism, fable, fiction, myth, have all come to mean something we can’t believe. Some parents in Victorian times wouldn’t let their children read novels because they weren’t “true.” But not many reasonable people today would deny that the poet is entitled to change whatever he likes when he uses a theme from history or real life. The reason why was explained long ago by Aristotle. The historian makes specific and particular statements as: “The battle of Hastings was fought in 1066.” Consequently he’s judged by the truth or falsehood of what he says — either there was such a battle or there wasn’t, and if there was he’s got the date either right or wrong. But the poet, Aristotle says, never makes any real statements at all, certainly no particular or specific ones. The poet’s job is not to tell you what happened, but what happens: not what did take place, but the kind of thing that always takes place. (35)