(Thanks to the Daily Dish)

Monthly Archives: November 2010

TGIF: Newswipe’s Fox Wipeout

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2aEk864YrKw

The BBC’s Charlie Brooker draws and quarters the more familiar demagogues of cable news.

Video of the Day: “The Coming Collapse of the Middle Class”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=akVL7QY0S8A

Elizabeth Warren — special adviser to President Obama on the development of the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau — is probably one of the most capable and decent people to serve in government in a very long time. She defies expectations when it comes to the pre-programmed yackety-yak of garden variety Washington power brokers. It is a startlingly refreshing experience to hear her address economic issues honestly and with a degree of respect and concern for the public interest that the public always deserves but almost never gets.

Above is a lecture she gave at UC Berkeley that predates by a year the collapse of financial markets in the fall of 2008.

(Thanks to Hugh McLeod for the tip.)

This Week in Climate Change: Water Vapor and Climate

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LAtD9aZYXAs

Eugene Ionesco

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FGOFBLHiVXU

An interview with Ionesco (French with English subtitles)

Today is playwright Eugene Ionesco‘s birthday (1909-1994).

Frye in The Educated Imagination:

I said earlier that there’s nothing new in literature that isn’t the old reshaped. The latest thing in drama is the theatre of the absurd, a completely wacky form of writing where anything goes and there are no rational rules. In one of these plays, Ionesco’s La Chauve Cantatrice (“The Bald Soprano” in English), a Mr. and Mrs. Martin are talking. They think they must have seen each other before, and discover that they travelled in the same train that morning, that they have the same name and address, sleep in the same bedroom, and both have a two-year-old daughter name Alice. Eventually Mr. Martin decides that he must be talking to his long lost wife Elizabeth. This scene is built on two of the solidest conventions in literature. One is the ironic situation in which two people are intimately related and yet know nothing about each other; the other is the ancient and often very corny device that critics call the “recognition scene,” where the long lost son and heir turns up from Australia in the last act. What makes the Ionesco scene funny is the fact that it’s a parody or take-off of these familiar conventions. The allusiveness of literature is part of its symbolic quality, its capacity to absorb everything from natural or human life into its own imaginative body. (40-1)

Carrie Nation

Carrie Nation: She’s wielding a hatchet for a reason

Today is the birthday of intemperate temperance advocate Carrie Nation (1846-1911).

Here is Frye on what turned out to be the tail end of the temperance movement in an editorial, “So Many Lost Weekends,” published in the March 1947 issue of The Canadian Forum. (A twofer: Frye gets in a good dig at “monopoly capitalism” along the way.)

The latest gathering of the Ontario Temperance Federation, which coincided with the lifting of the liquor ration, included an abortive proposal to form a temperance party. It is with genuine concern that one sees the public utterances of Protestant churches increasingly identified with the impression that their churches regard the “liquor traffic” as of far greater importance than any theological doctrine, any other social question, or any other moral weakness. We say weakness, for the refusal to make any moral distinction between drinking and drunkenness constitutes a grave social problem; but unfortunately the effect of losing all sense of proportion about it is to make it seem almost trivial. And it can hardly be denied either that many clergymen have completely lost their sense of proportion about drinking, and have transformed a real issue into a superstitious taboo which is injurious to religion (it has, for example, alienated a large number from the churches whose support could have been had for the asking), which has no intelligible relationship to politics, and which is steadily losing all connection with doing good.

Many temperance advocates are only church politicians, but many are men with long and honourable careers in the support of liberal and socialist causes — a fact which is reflected in a certain realism with which they associate the drinking problem with profits and private enterprise. One is all the more surprised, therefore, to find them falling into the common reformers’ error of mistaking the effect for the cause. People take to drink because of psychological maladjustments or economic insecurity. The former any serious religion would regard as falling with the province of the “cure of souls”; the latter is an evil which nothing but an intelligently planned socialist movement can really cure. Socialists ask for the support of the Christian churches on the ground that the present system of monopoly capitalism is immoral as well as inefficient; and to divert all of one’s reforming energies from the central problem of insecurity to one of its by-products is, as drunkenness is, like pulling a leaf from a tree and expecting the tree to wither away. (CW 4, 246-7)

Joan of Arc

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MqMBHWmTcC8

The first part of a restored version of a previously lost 1927 film, La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc

On this date in 1429 Joan of Arc unsuccessfully besieged La Charité.

Frye on prophesy in The Great Code:

In the post-Biblical period both Christianity and Rabbinical Judaism seem to have accepted the principle that the age of prophecy had ceased, and to have accepted it with a good deal of relief. Medieval Europe had a High King and a High Priest, an Emperor and a Pope, but the distinctively prophetic third force was not recognized. The exceptions prove the rule. The career of Savonarola is again one of martyrdom, and the same is true of Joan of Arc, who illustrates the inability of a hierarchical society to distinguish a Deborah from a Witch of Endor. (CW 19, 148)

James Pollock: “Northrop Frye at Bowles Lunch”

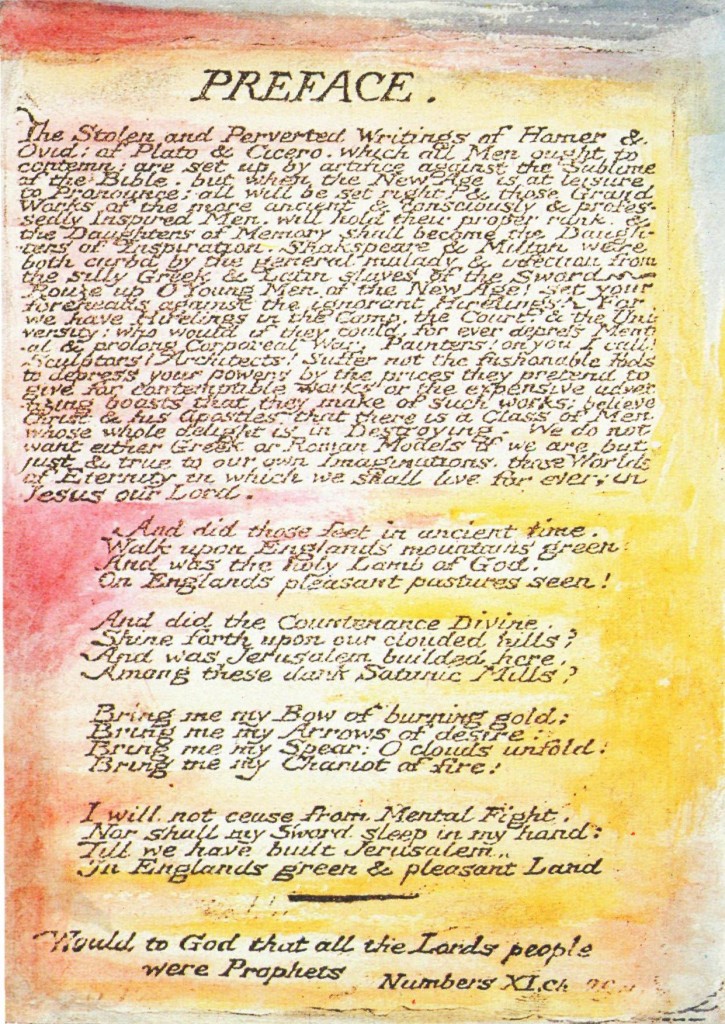

The Preface to Blake’s Milton

James Pollock’s new poem about the young Norrie in the latest issue of Agni here.

“I have had sudden visions.”

Bloor Street, Toronto, 1934

3 a.m. in the all-night diner, dizzy

with Benzedrine and lack of sleep, old books

and papers scattered across the table.

With his pen, his Dickensian spectacles,

his pounding, driving Bourgeois intellect,

he charges into a poem by William Blake

with two facts and a thesis, cuts Milton

open on the table like a murdered corpse

and spins it like a teetotum until

he’s put each sentence through its purgatory

and made the poet bless him with a sign:

thus (though perhaps one can picture this

only from a point outside of time)

he sees the shattered universe around him

explode in reverse, and make the flying

shards of its blue Rose window whole again.

Thespis

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZYEu8l6Q5RI

The opening of Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound (ca. 455 BCE), performed in the original Greek

On this date in 534 BCE Thespis of Acaria became the first actor to portray a character onstage.

Frye in “The Language of Poetry” refers James Frazer’s The Golden Bough to the primitive and popular element of ritual in drama:

The work of the Classical scholars who have followed Frazer’s lead has produced a general theory of the spectacular or ritual content of Greek drama. But if the ritual pattern is in the plays, the critic need not take sides in the quite separate historical controversy over the ritual origin of Greek drama. It is on the other hand a matter of simple observation that the action of Iphigenia in Tauris, for example, is concerned with human sacrifice. Ritual, as the content of action, and more particularly of dramatic action, is something continuously latent in the order of words, and is quite independent of direct influence. Rituals of human sacrifice were not common in Victorian England, but the instant Victorian drama becomes primitive and popular, as it does in The Mikado, back comes all Frazer’s apparatus, the king’s son, the mock sacrifice, the analogy with the Sacea, and the rest of it. It comes back because it is still the primitive and popular way of holding an audience’s attention, and the experienced dramatist knows it. (CW 21, 220)