httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BSZrmbgO4pY

A short piece about Eco produced in 2009

Today is Umberto Eco‘s birthday (born 1932).

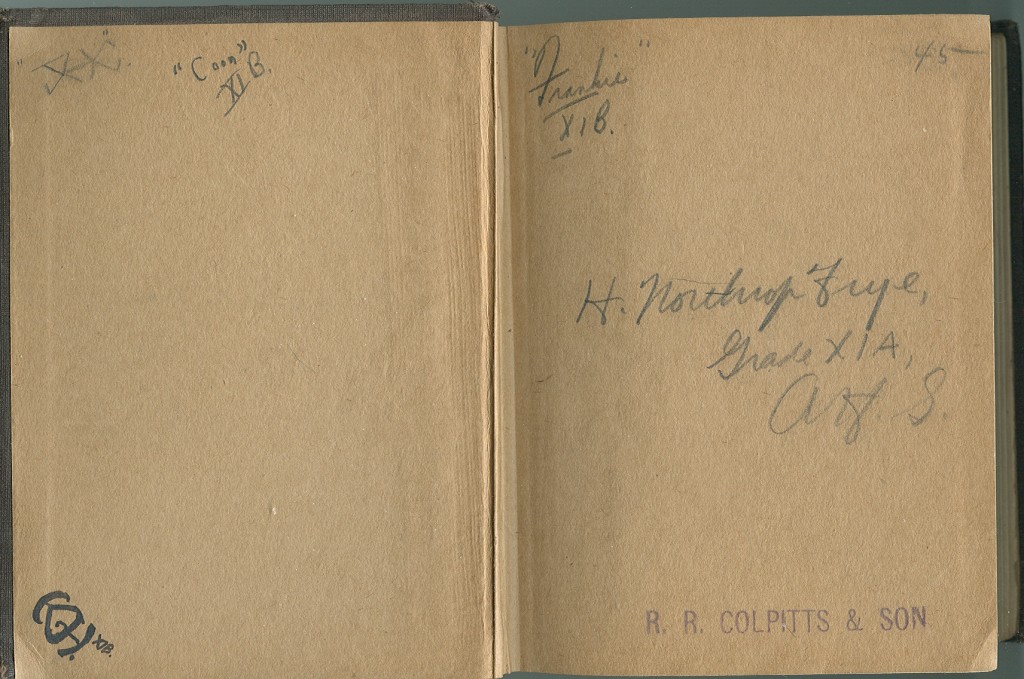

Frye in an interview with Eco in Milan:

Eco: You have spoken of romance as a polarized narrative — good and evil, black and white — a structure similar to that of chess. In The Secular Scripture, you refer briefly to the fact that the university unrest of 1968 produced “manic” situations; and you also suggested (even while attributing the idea to others) that there was a link between the polarized paradigm of war (us versus them, the enemy) and the structures of television and melodrama. If this is so, do you see the new taste for romance as the result (even the sublimation of) that generation’s point of view?

Frye: I referred earlier to the two levels of realism: the level that accepts the veneer of social authority, and the level that penetrates and goes beyond it and that is the genuine form of realism. Advertising and propaganda reinforce the veneer, the appearance, of the social, and the invention of television has made the impact so overpowering that, in America, the youngest generation, starting from at least 1965, has been pushed almost to the point of hysteria. It has not been able to grasp a sense of the reality that goes beyond the veneer: it has not produced a Marx who could offer a comprehensive understanding of how the surface was contrived, as Marx did in his analysis of capitalism. All that they could do was adapt and regurgitate the categories of television itself: the struggle between the good guys and the bad, between the forces of light and darkness. Enemies were described in paranoid terms such as “the politico-military establishment.” I don’t see how a different point of view is realistically possible for sensitive, imaginative young people, although there are, certainly, enormous dangers inherent in transforming a conflict into an apocalypse. The most promising approach is to see the struggle as a clash of ideas rather as one of individuals. (CW 24, 447-8)

Here’s John Ayre’s account of the interview in his biography of Frye:

In Milan…Frye was taken out to dinner by an admiring Bologna-based semiologist by the name of Umberto Eco representing the journal alfabeta. While Eco had consulted with his fellow editors about appropriate questions, the “interview” itself was an impromptu performance. Far from thrusting a microphone in his face, Eco took Frye out to dinner and scribbled out questions on a napkin for Frye to answer later based on the recently translated The Secular Scripture. Eco himself was just a half-year away from finishing the phenomenally successful The Name of the Rose, and his non-fictional Postscript showed interesting echoes from Frye’s book. (370)

And, finally, here’s Frye in an interview conducted for Acta Victoriana:

The distinction between popular culture and highbrow culture assumes that there are two different kinds of people, and I think that’s extremely dubious. I don’t see the virginal purity of highbrow literature trying to keep itself unsullied from the pollutions of popular culture. Umberto Eco wasn’t any less a semiotics scholar for writing a bestselling romance [The Name of the Rose]. There isn’t a qualitative distinction. It just doesn’t exist. And I think that the tendency on the part of the mass media as a whole is to abolish this distinction. (CW 24, 766)