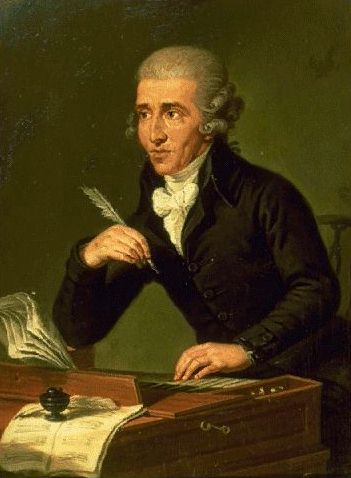

Further to Michael’s post, Frye on Haydn in Notebook 5

If I had such a thing as a favorite composer, it would be Haydn. I think it’s Haydn anyway. I’m going to write something on him someday. More and more I find myself turning to Bach & Haydn, which means more & more away from Mozart. Mozart’s a skeptic & Haydn’s a Christian. Haydn has everything. He has all of Schubert’s ease of melody sags or goes soupy the way Schubert does. He’s as witty as either Mozart or Scarlatti: I’ve just read through 37 minuets & 24 German dances, a grueling test for any composer & he says something pointed & epigrammatic practically every time. But he has more than wit: he has an amazing eloquence & range in his melodic line: he can be marvellously “singable” & yet swoop over everything form a soprano to a bass range: D major sonata in Book I with the lovely long Adagio. He may not be as profound a thinker generally as Mozart, but I think he’s a greater thinker in musical form than Mozart: he has a sense of organic unity about him & an originality of creative thought, still in musical form, Mozart hasn’t. Haydn develops a plot; Mozart works out a situation. But the plot really develops, that’s the point. He had much more influence over Beethoven than Mozart, I think, particularly in things like the Pathétique: only Beethoven is analytic & disruptive where Haydn is synthetic. He’s really almost more radiant than Beethoven for that reason. His trios are more fun to read on a piano than Mozart’s because they’re all piano & Mozart’s are balanced: Mozart’s are more expertly written, but it’s plot & situation again, & Haydn’s more fun. In things like the G major sonata, Book II, slow movement, his impersonality, gone serious, just drops you out of sight: he’s too wrapped up in pure music ever to be sad or cynical, like Mozart. He hits cold depths of ice Mozart doesn’t get down to because he doesn’t believe enough. Sometimes the coldness of pure Rococo, the winter-chill of our autumnal culture: slow movement of C major quartet, op. 59 No. 2 or something in the fifties: 55, I guess. But that doesn’t mean he’s an abstract music writer. Sometimes Bach is unplayable, either because, as in the Art of Fugue, he’s just writing absolute music, or because he’s gone beyond all reading or reproduction into pure thought, as in the C# minor of the WTC I [The Well-Tempered Clavier, book 1]. Sometimes Beethoven’s unplayable when he’s appealing to a wrench in the guts too physical for a performance to reach, as in the Coriolan or the 106. (That doesn’t necessarily mean greatness, any more than an unactable play is necessarily great because King Lear is unactable). But Haydn always has a powerful ease of reproduction: his music exists only for performance. His piano sonatas are in one idiom, his string quartets in another, etc. That’s why he’s the easiest of all composers to play: he thinks so purely in terms of the genius of reproducing instruments. Hence he’s an amateur-family musician, and could do what the Bible could almost have done (not quite: its achievement is overrated) for amateur-family English prose style. He’s probably the only great composer who could have written a national anthem. But he’s got something ultimate in his time & Mozart & Beethoven & Goethe haven’t: there’s too much Goethe in Mozart and too much Beethoven in Goethe. Something of the rebirth of imagination: the thing Blake had. Haydn was no Bach and couldn’t do the Mass or Passion job to save his soul, if it had ever been in any danger, but the Creation does give the perfect Paradise-existence of the imaginative mind: the super-pastoral note. I daresay the Seasons is the same thing: I haven’t heard or read it, but winter is as pastoral an idea as summer. He’s been so grossly underrated for the same reason that Mozart used to be: a supreme genius of comedy, patted on the back for being amusing, like Dan Chaucer and gentle Shakespeare—the Papa Haydn approach. Chaucer, being ironical, is Mozartian; Haydn’s closer to the 13th c. (Notebook 5, CW 25, 163–5)