Further to Michael’s post, Frye and Helen on Jackson in the Correspondence.

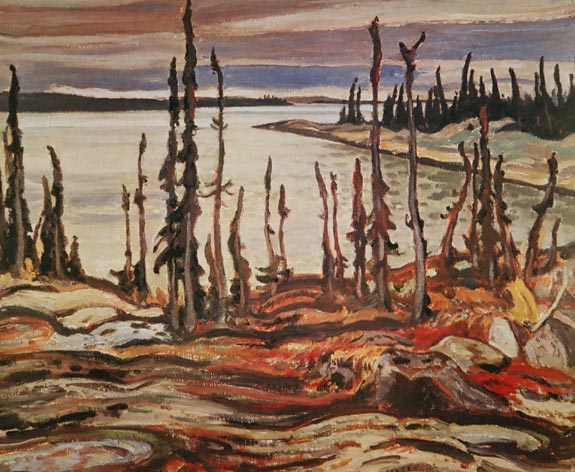

Canadian landscape painting has to deal with a sharp hard light and solid blocks of clear colour: consequently a tendency to conventionalize outlines has been inherent in it from the first. Thomson, being interested in problems of linear distance and in the breaking up of light which they suggest, dodged this tendency, but it is strong in Jackson and Emily Carr, and of course far stronger in Lawren Harris, who saved himself from dropping into a facile formula (like Rockwell Kent) by turning to out-and-out abstract painting. (CW 12, 12)

The Group of Seven felt that they were among the first to look at Canada directly, and much of their painting was based on the principle of confronting the eye with the landscape. This made a good deal of their work approach the flat and posterish, but that was a risk they were ready to take. Jackson, Lismer, and Harris all found this formula exhaustible, and have all developed away from it. Thomson and Emily Carr represent a more conscious penetration of the landscape: they seem to try to find a centre of rhythm deep within their subject and expand from there. Milne combines these techniques in a way that is apt to confuse people who look at him for the first time. (CW 12, 73)

I am, of course, deeply appreciative of the honour that Carleton University has done me. It is particularly an honour to receive this degree in the company of Mr. A.Y. Jackson, as well as a great pleasure, because Mr. Jackson is an old friend. (CW 12, 272)

Writers don’t interpret national characters; they create them. But what they create is a series of individual things, characters in novels, images in poems, landscapes in pictures. Types and distinctive qualities are second-hand conventions. If you see what you think is a typical Englishman, it’s a hundred to one that you’ve got your notion of a typical Englishman from your second-hand reading. It is only in satire that types are properly used: a typical Englishman can exist only in such figures as Low’s Colonel Blimp. If you look at Mr. Jackson’s paintings, you will see a most impressive pictorial survey of Canada: pictures of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior, pictures of the Quebec Laurentians, pictures of Great Bear Lake and the Mackenzie River. What you will not see is a typically Canadian landscape: no such place exists. In fiction too, there is nothing typically Canadian, and Canada would not be a very interesting place to live in if there were. Only the outsider to a country finds characters or patterns of behaviour that are seriously typical. Maria Chapdelaine has something of this typifying quality, but then Maria Chapdelaine is a tourist’s novel. (CW 12, 275)