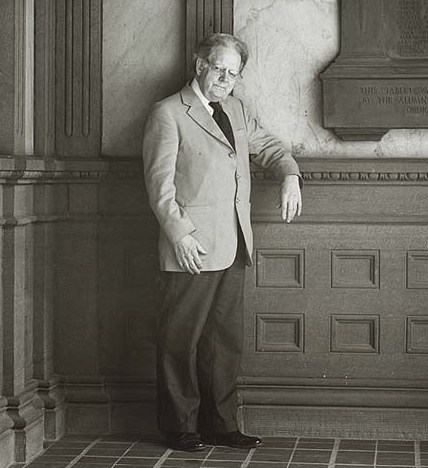

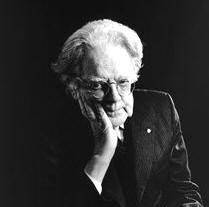

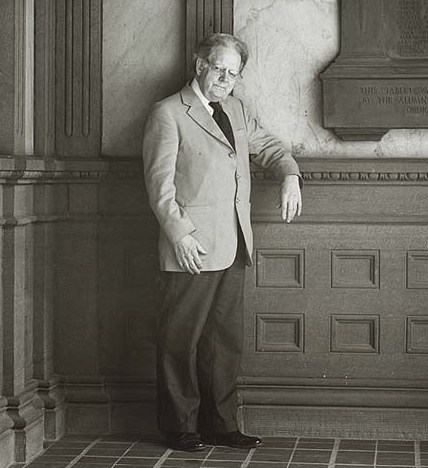

Today is Frye’s birthday, and it has been just about two weeks since we heard the news that the Dean of Arts and Sciences, Meric Gertler, and the Strategic Planning Committee had recommended the closure of the Centre for Comparative Literature which Frye founded 40 years ago. The news was a complete shock. The director of the Centre, Neil ten Kortenaar, in his letter to the dean begins with this very admission:

My initial shock at the news of the proposed disestablishment of the Centre for Comparative Literature has become absolute dismay as the meaning of this proposal has become clear to me. The news comes at a time when Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto was being thoroughly reinvigorated and we were looking forward with excitement to our future.

I can only agree with these sentiments. I was initially shocked by the recommendation and then slowly but surely began to realise the ramifications of such a decision. Ten Kortenaar cites a number of these in his letter.

But, on a much more personal level, the type of research that I do simply cannot be done elsewhere. I chose to attend the University of Toronto, and more precisely the Centre for Comparative Literature, because of its connections to Northrop Frye. When I arrived at the University, I told the faculty of the Centre that my project would focus on Frye’s influence, especially with respect to Harold Bloom. Indeed, in October, I submitted to the Centre a SSHRC proposal called, “Anxieties of Criticism, Anatomies of Influence: A Study of Northrop Frye and Harold Bloom.” In April, I found out that I had been awarded a SSHRC. Since then I have written an article with a very similar title that recently appeared in the Canadian Review for Comparative Literature. It may appear that I could have completed this research anywhere. But that is not the case, I very much needed the University of Toronto and the Centre for Comparative Literature because it provided the archives and the intellectual guidance of people like Linda Hutcheon, J. Edward Chamberlin, and Eva Kushner.

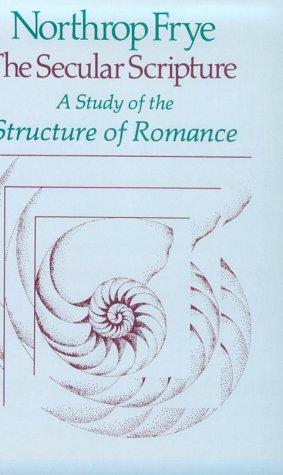

My current research continues with ideas stemming from Northrop Frye’s theories of literature, particularly romance. My dissertation considers literatures written in English, Spanish, French, and Portuguese. This dissertation simply could not happen elsewhere. The study follows Frye’s dictum that “popular literature […] is neither better nor worse than elite literature, nor is it really a different kind of literature” (CW XVIII:23); and thus, my study includes everything from George Eliot and Marcel Proust to Twilight and Harlequin romances. Only the Centre for Comparative Literature could provide a home for such research and only the Centre would encourage such research. The Centre has afforded me many opportunities to explore romance and present these ideas at international conferences. In April, I was at the American Comparative Literature Association’s meeting in New Orleans and NeMLA meeting in Montreal; in May at Congress in Montreal where I presented at the Canadian Comparative Literature Association’s meeting as well as the Canadian Association of Hispanists, in August I will be at the International Association for the Study of Popular Romance’s conference, and in September at a conference on monsters at Oxford.

I look around now at the Centre for Comparative Literature and realise that this Centre is, even in its darkest hours, a powerhouse for intellectual inquiry. Today, the Centre found itself on the front page of the Globe and Mail receiving national exposure. I think I can say that for many of my colleagues this was a huge – and much needed – surprise.

I urge readers of this blog to consider the future of Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto. We have a series of ways you can follow our story and I provide to you a series of links:

www.savecomplit.ca — Main Resource and Information Page; if you send letters to the Dean, Provost, and President, we will happily publish them here. All media stories will be included on this webpage.

www.PetitionOnline.com/complit/petition.html — Petition to Save Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto. Major figures in Comparative Literature have already signed (as have many Frye Scholars): Ian Balfour, Svetlana Boym, Rey Chow, Jonathan Culler, Jonathan Hart, Nicholas Halmi, Linda Hutcheon, Andreas Huyssen, Ania Loomba, Franco Moretti, Tilottama Rajan, Germaine Warkentin.

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Save-Comp-Lit-at-U-of-T/128346170533811 — A Facebook page with information as it becomes available.

http://twitter.com/SaveComplit — Our Twitter account which will post links to news stories.

And, of course, we will continue to update the Frye community here at The Educated Imagination.