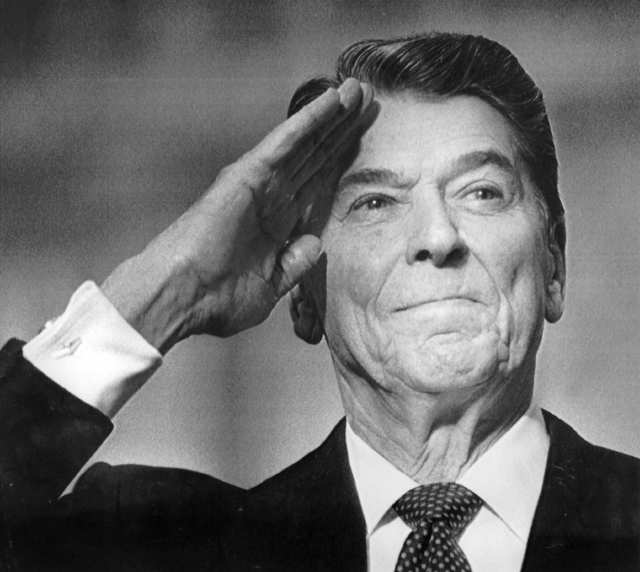

Further to Joe’s post, more Frye on Reagan:

Of course it takes some effort to become more self-observant, to acquire historical sense and perspective, to understand the limitations that have been placed on human power by God, nature, fate, or whatever. It was part of President Reagan’s appeal that he was entirely unaware of any change in consciousness, and talked in the old reassuring terms of unlimited progress. But the new response to the patterns of history seems to have made itself felt, along with a growing sense that we can no longer afford leaders who think that acid rain is something one gets by eating grapefruit. I wish I could document this change from recent developments in American culture, but I am running out of both time and knowledge. It seems clear to me, however, that American and Canadian imaginations are much closer together than they have been in the past. (CW 12, 653)

Both Governor Reagan and the local SDS issued statements, and there is a curious similarity in their statements. They both say that the people’s park was a phoney issue, and that the real cause was a conspiracy—the Governor says of hard-core student agitators, the SDS says of right-wing interests operating “probably at the national level.” Both are undoubtedly right, up to a point. There is a hard core of student agitators: one of them was grumbling in the student paper, a day or two before the lid blew off, that “not a goddam thing was happening at Berkeley,” and that something would have to start soon because Chairman Mao himself had said, in one of his great thoughts, that revolution is no child’s play. On the other side, Governor Reagan is clearly staking a very ambitious career on the support of voters who want to have these noisy young pups put in their place once and for all. Both are very pleased with the result: the Governor is visibly admiring his own image as a firm and sane administrator, and the SDS are delighted that the police have “over-reacted” so predictably and helped to “radicalize the moderates.” But the more one thinks about these two attitudes, the clearer it becomes that the militant left and the militant right are not going in opposite directions, even when they fight each other, but in the same direction. For both the Governor and the SDS, the university is ultimately an obstacle, which will have to be destroyed or transformed into something unrecognizable if their ambitions are to be fulfilled. (CW 7, 386-7)

At Berkeley, one sees clearly how the supporters of Governor Reagan and the supporters of SDS are the same kind of people. The radical talks about the thoughts of Chairman Mao, not because he is really so impressed by those thoughts but because he cannot endure the notion of thought apart from dictatorial power. The John Bircher uses slightly different formulas to mean the same thing. In the past week I have seen, and heard about, the most incredible acts of police brutality and stupidity against the students. And yet even this is not one society repressing another, but a single society that cannot escape from its own bungling. Whatever we most condemn in our society is still a part of ourselves, and we cannot disclaim responsibility for it. (ibid., 392)

The Soviet Union is trying to outgrow the Leninist dialectical rigidity, and some elements in the U.S.A. are trying to outgrow its counterpart. But it’s hard: Reagan is the great symbol of clinging to the great-power syndrome, which is why he sounds charismatic even when he’s talking the most obvious nonsense. (CW 5, 398)

BILL MOYERS: I’ve often thought that one of the secrets of Ronald Reagan’s appeal was that he was able to make Americans feel as if we were still the mighty giant of the world, still an empire, even as around the world we were having to retreat from the old presumptions that governed us for the last fifty years. Did you see any of that in the Reagan appeal?

FRYE: Oh yes, very much so. It’s the only thing that explains the Reagan charisma. In fact, I think that what has been most important about Americans since the war is that they have been saying a lot of foolish things—the Evil Empire, for example—but doing all the right ones. I think nobody but Nixon could have organized a deal with China, for example. (CW 24, 893-4)