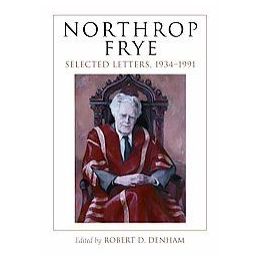

From Northrop Frye: The Selected Letters, 1934-1991, ed. Robert D. Denham (Jefferson, NC, and London: McFarland & Co., 2009)

Letter to Robert Heilman, 29 October 1951

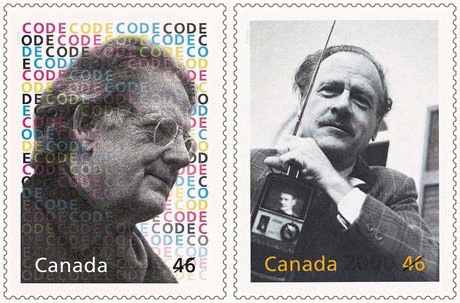

. . . I am very deeply obliged to you for being responsible for my having a wonderful summer. I have seldom enjoyed a summer so much. We topped it off with ten days in San Francisco and two weeks in New York—one at the English institute, which turned out to be a very good one. I got Marshall McLuhan down to give a paper [“The Aesthetic Moment in Landscape Poetry,” in Alan Downer, ed., English Institute Essays (New York: Columbia University Press, 1952), 168–81; rpt. in The Interior Landscape: The Literary Criticism of Marshall McLuhan 1943-1962, ed. Eugene McNamara (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1969), 91–7].

Letter to Richard Schoeck, 24 November 1965

You may know that Marshall and Ernest have asked me to do a collection of comments on myth and criticism as one of the Gemini books. I gather that their original idea was to collect contemporary essays on the subject, but I thought it might be more interesting and useful to go back into the history of the tendency. Things like Raleigh’s History, the opening of Purchas, Camden, Reynolds’ Mythomystes, Bacon’s Wisdom of the Ancients, Sandys’ Ovid, from that period; some of the “Druid” stuff from around Blake’s time; some of the material used by Shelley and Keats, and so on down to Ruskin’s Queen of the Air, but without incorporating anything much later than The Golden Bough and the turn of the century. An introductory essay would of course indicate the relevance of this to what came after Frazer. I’ve spoken about this to Marshall and he suggested that I might consult the other editors. [Frye wrote a preface for the proposed collection, but the project was for some reason aborted. His preface was published forty years later in CW 25:326–8.]

Letter to John Garabedian, 12 September 1967 [In reply to an letter by Garabedian (1 September 1967), a feature writer for the New York Post, wanting Frye to expand on a comment quoted in an article in Time magazine that hippies were inheritors of the “outlawed and furtive social ideal known as the ‘Land of Cockaigne.’” The Time article also referred to Frye as a disciple of McLuhan.]

Thank you for your letter. I am not sure that I can be of much help to you, as I did not have hippies in mind when I spoke of the Land of Cockaigne as one form of Utopia. The association was due to the Time writer, and I doubt very much that the Land of Cockaigne is really what the hippies are talking about. Neither was it correct to describe me as a disciple of McLuhan, although he is a colleague and a good personal friend.

Letter to Walter Miale, 18 February 1969

. . . Korzybsky was, because of his anti‑literary bias, a person I was bound to have reservations about, but there was still the possibility that he might be, like Marshall McLuhan today, probing and prodding in directions that might turn out to be useful.

Letter to Walter J. Ong, S.J., 28 March 1973

. . . I saw Marshall [McLuhan] the other day at a meeting on Canadian Studies, where we were discussing the question of how difficult it is for students in this bilingual country to acquire a second language when they don’t possess a first one.

Letter to William Harmon, 13 August 1974

Harmon had requested (8 July 1974) the source of Joyce’s referring to Eliot as “the Bishop of Hippo,” which Frye quotes in his book on T.S. Eliot (pp. 67–8). Frye replied that he wasn’t certain as he was quoting “orally from someone who had been working in the Joyce papers at Buffalo.” Harmon responded with a note of thanks, which prompted Frye to write again to say “Marshall McLuhan was present when this tag from Joyce was quoted, and his memory of it may be more accurate than mine.”

Letter to Richard Kostelanetz, 7 January 1976

. . . Please don’t make me an enemy of Marshall McLuhan: I am personally very fond of him, and think the campus would be a much duller place without him. I don’t always agree with him, but he doesn’t always agree with himself.

The statement of Colombo’s on page 16 strikes me as curious, but it’s your article. [John Robert Colombo had said that “McLuhan and Frye are Canada’s Aristotle and Plato. McLuhan is the scientist, and Frye the mystical theorist, with the eternal paradigms and everlasting forms” (qtd. by Kostelanetz, Three Canadian Geniuses, 131).]

Letter to Andrew Foley, 20 April 1976

. . . I think psychologists are now moving away from the Freudian metaphors about an unconsciousness buried below a conscious mind, and are thinking more in terms of the division in the brain between the hemisphere controlling a linear and verbal activity and the one that is more spatially oriented. It seems to me that the most important aspect of McLuhan is his role in the development of this conception.

Letter to Fr. Walter Ong, December 1977

. . . I saw something of your student Patrick Hogan this year, but he left early. I don’t know whether he was disappointed in what we did or didn’t do for him. He was very keen, and one of his proposals was that he and Marshall and I should form a seminar to discuss Finnegans Wake, which hardly fitted my working schedule or, I should imagine, Marshall’s.

Letter to Barrington Nevitt, 20 September 1988

This is in connection with your letter about your proposed book on Marshall McLuhan. I am sorry if I am unhelpful on this subject, but I doubt that I have anything very distinctive to say on the subject. What I could say I said at the teacher’s awards meeting you referred to [Distinguished Teacher Awards, December 1987], but unfortunately I had no text for that talk. I think I remember saying that Marshall was an extraordinary improviser in conversation, that he could take fire instantly from a chance remark, and that I have never known anyone to equal him on that score. I also feel, whether I said it or not, that he was celebrated for the wrong reasons in the sixties, and then neglected for the wrong reasons later, so that a reassessment of his work and its value is badly needed. I think what I chiefly learned from him, as an influence on me, was the role of discontinuity in communication, which he was one of the first people to understand the significance of. Beyond that, I am afraid I am not much use.