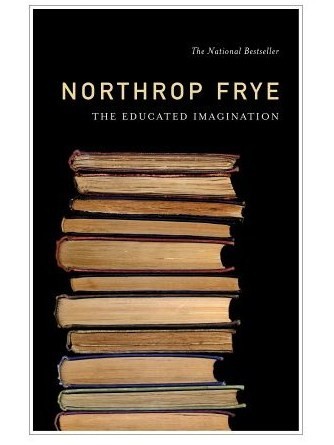

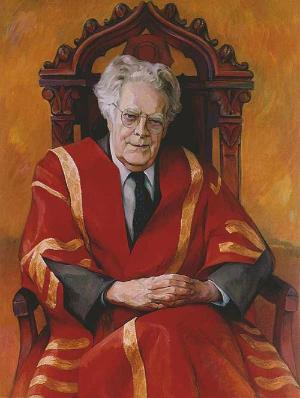

I’ve recently been shelving some of the volumes I inherited this summer following the death of my much-missed colleague and friend Edward Twining. As I stacked some of them, I remembered how when we first came to Denver, Ed and his wise and witty wife Mary-Beth took us on a drive into the Rocky Mountains. As we rose in altitude, Ed began to recollect, with all the vigor and enthusiasm he commanded so easily, the occasion of Frye’s visit to Denver about twenty years before. Unusually, I thought then—but not now—he warmed to the memory of Frye’s unassuming and apparently capacious knowledge of the region’s geology. (I was later to discover that Frye had been a longtime lunch partner of Charles Currelly, Professor of Geology at Toronto and had ghost-edited [ghost-written?] his volume of reminiscences We Brought the Ages Home.) Throughout, Ed punctuated his discussion with regular, and obviously warmly felt, exclamations like “What a generous mind! What an honest man!” There was no reference to Frye’s various institutional and professional honors, still less any asides about cultural power or academic acclaim. Although there were frequent reflections on admired passages from unexpected sources—the CBC broadcasts that became The Educated Imagination and The Great Code.

It was the professional Frye with whom I started to reacquaint myself as I continued in my shelving. My own paperback edition of The Stubborn Structure is no longer stubborn—invertebrate might be a more appropriate adjective. So a hardback copy was most welcome to me. As I started to leaf through the book, thoughts rapidly started to form. I became particularly interested in the essay on “The Instruments of Mental Production.” In the rest of this entry, I shall be largely concerned with what Frye says in this piece, but I pause for a moment to note that I think the network of connections he forged with universities across the world is worth thinking about: what is the relationship between the international Frye and the Frye of the 40s and 50s, who wrote for The Canadian Forum. How did he adjust his discourse to the different conditions of his utterances at that time?

One answer is of course that he didn’t, unlike many contemporary academics, who are conference revolutionaries and weekend consumers of Gucci. Instead, he brought to different audiences the fruits of what he discovered in Blake and Milton. In so doing, he rejected the premises that liberal or humanistic knowledge was ever instrumental, or that the language of ownership and production had much to do with what we do when we teach King Lear or Emma. He reiterated his conviction that education in “the creative arts” was intimately concerned with structured possibilities, not just with fitting bits of the curriculum together in what a faculty might be willing to accept after long processes of consultation and self-study had worn them down into demoralized exhaustion. He emphasized how much of what was most valuable in a liberal education was not negotiable in a roundtable manner, but depended on self-identification, unconscious commitments and, memorably, the articulation of inner vision into structured communication. “It is worth reminding ourselves,” he says, “that in Plato, who seems to have invented the conception, dialogue exists solely for the purpose of destroying false knowledge. As soon as any genuine knowledge (or what Plato regarded as such) is present, the dialogue turns into a punctuated monologue” (SS 4).

There is no substitute for reflection in the educated imagination, not any escaping the need to translate the results of that reflection into organized utterance. A punctuated monologue is not a dialogue, but it isn’t a withdrawal into deep silence either. Because even if your commitments or preferred forms of identification are not with those of a humanist education, you will still need to use the humanist instruments of word and image to communicate them. This is why a humanistic education is so seminal for Frye and for us.

I’ve been thinking about these things as I stacked some of Ed Twining’s books, and wondering if it wasn’t for reasons like these that Frye could have meant so much to a man who, for all his large reserves of play and erudition, would surely have perished in the present academic dispensation. Not so much because this regime emphasizes constant publication—in fact many administrators are anything but concerned about publication—but because we are now so pinioned on the treadmill of constant production that Frye identified in this essay as so deeply anti-educative. Only now the things we aim to produce are not articles and monographs but tolerance, a comfortable learning environment, the public good and God knows what else. In this, the postmodern academy is so often only a parody of what Frye talks about in “The Instruments of Mental Production.” Instead, it is a place best imaged in Book 4 of Gulliver’s Travels where, you will remember, Gulliver talks about the proneness to disease of the Yahoos. What strikes him as odd is that no one has: “Any more than a general Appellation for those Maladies, which is borrowed from the Name of the Beast, and called Hnea Yahoo or the Yahoo’s-Evil; and the Cure prescribed is a Mixture of their own Dung and Urine, forcibly put down the Yahoo’s Throat” (GT 4).

The perpetual administration of dubious remedies is what the postmodern academy craves and thrives on, not productive scholarship (identified as the source of rich ironies by Frye) and still less the possibilities of human life that he enjoins on us for our lifetime study in his final paragraph. But even the impossibilities, even what you don’t want, ultimately assumes “a poetic shape” as this passage from Swift shows.

In circumstances like these, I think Frye’s international presence in the scholarly community brings him into territory contemporary readers will recognize from Adorno’s Minima Moralia. Adorno’s response, it seems to me, is much more like Gulliver’s: recalcitrant misanthropy takes over from hope and, to a degree, vision—much of his discussion in MM proceeds like a discharge of tiny pellets into his own flesh. I’d like to say that, of course, Frye’s is the example we all should follow. But I’m not at all sure about this: what I do think is that the global context that a particular kind of inquirer moves towards seems to produce utopian and misanthropic types in the scholarly drama it hosts. I mean types to carry the meaning Frye has alerted us to: recurring figures in a specific structure.