Todd Lawson is professor of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto

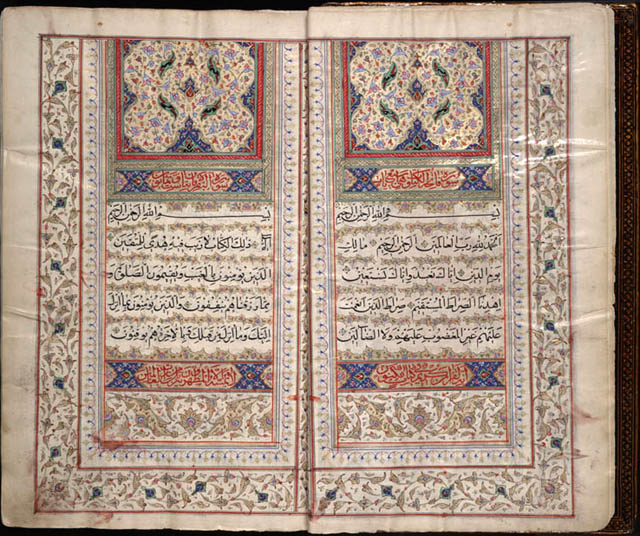

In several, scattered places in his later writings, Frye treats the Koran as a text that deserves to be read very carefully as both literature and “more than literature”. For example, in The Great Code he points out that those who see in the Koran’s version of the story of Mary and the birth of Jesus a confusion of Biblical material have simply got it wrong and are deaf to the music of typological figuration.

The third Sura of the Koran appears to be identifying Miriam and Mary; Christian commentators on the Koran naturally say this is ridiculous, but from the purely typological point of view from which the Koran is speaking, the identification makes good sense. (GC 172, italics added)

Several similar instances demonstrate Frye’s characteristic perspicacity and even unto a text as foreign in cultural presuppositions, form and content as the Koran. I am studying Frye’s relationship with the Koran through both printed and unpublished works where he either explicitly refers to the text or where his remarks on other texts are equally apposite in the case of the Koran. I am also exploring, with the able and valuable assistance of Rebekah Zwanzig (who actually also discovered this blog), the Frye archive to study his marginalia and notes on related texts, such as English translations of the Koran and of Rumi’s poetry. Results so far suggest that Frye’s faith in the “sacrament of reading” allowed him to develop a remarkably open, if critical, attitude towards the Koran, something in which he was certainly then – and may still well be – ahead of his time.

My interest in Frye’s Koran began in the early ‘80’s when I was working on a PhD thesis at McGill’s Institute of Islamic Studies. My subject was a particularly challenging unpublished manuscript of an Arabic Koran commentary. In taking a break, reading the newly published Great Code, I saw that Frye had solved one of the problems that had been eluding me. His discussion of the above-mentioned typological figuration and its persuasive power and efficacy was in fact a revelation and provided a key I had not found elsewhere. When I started teaching at U of T in 1988 I secretly held the hope that I would one day be able to meet the great man and express to him my gratitude for his unbeknownst help. Of course, I also hoped of thus being able to search further the Frygian experience of the Koran. Alas, this meeting never happened. In fact, and in the context of the present research, a rather ironic signal brought the possibility to a clear, cold end . . . it was the evening of January 23, 1991. In those days I was in the habit of listening to the radio about the Gulf War while I worked in the evening in my office at Robarts Library. The bombing of Baghdad — home and scene of the great efflorescence of Arabo-Islamic learning and culture from the 8th to the 13th centuries — had begun five or six days earlier and was commencing apace. The reports of this massive (and in retrospect perhaps phobic) attack were interrupted on the CBC to announce the passing of Northrop Frye. He had just been there, virtually across the street. Now he was gone. But, it seems, not forever.

Fifteen years later, I decided to have our conversation anyway. Having returned to the University of Toronto from McGill, and encouraged in my general research by a SSHRC award to study the Koran as an example of literary apocalypse, I decided to weave Frye’s very illuminating work into my methodology. In order to be as rigorous as possible about this, I organized two successive, year-long graduate seminars, entitled the Koranic Apocalyptic Imagination, around the above-mentioned later works of Frye, which included the Double Vision. It was as if the students recognized a long lost friend. It is amazing the way these young Islamicists became excited and encouraged by Frye’s remarks about the structure and content of the Bible because they could apply many of them to their own reading of the Koran, a text which for many of the students was certainly more than literature. And they also discovered how it was literature as well.

The current project, bringing into some kind of order the various aspects, apparent contradictions and other problems of a Frygian Koran, is meant to be background for a chapter in the eventual monograph on the Koran as apocalypse, a topic that has thus far attracted an astonishing lack of attention. Why this lack of attention? It is an interesting question, but one which I will forbear from addressing here. I look forward to hearing from scholars who may be interested in or actually working on Northrop Frye’s reading of the Koran and his understanding of Islam. I am grateful to Bob Denham for the extremely helpful postings here on Frye and the Koran and for general encouragement. And I am grateful to Michael Happy for passing along my initial note to the blog to Bob and, of course, for all of his hard work and creativity that has gone into this invaluable website.