Responding to Russell Perkin’s Celebrity Critics:

Your post reminded me of the last popular critic who had a bestseller on the NY Times List, Harold Bloom, the disciple of Frye, more akin to Judas than Peter. (Frye did say he disliked disciples, as one will betray you anyways.)

The Invention of the Human and The Western Canon were huge and had great implications for literature and literary critics.

I have been reading Terry Eagleton, and he is not my cup of tea. Not only did I feel he misrepresented Frye in his Literary Theory potboiler; he also took many riffs off of Frye. Read Frye’s “Polemical Introduction” in the Anatomy and compare it to Eagleton’s introduction of Literary Theory. Eagleton has a similar outline, if not the arguments.

I feel he made his critical mark, like other critics, by knocking Frye, in a classic David versus Goliath. I still think Eagleton and critics like him turned out to be the real Philistines.

In Response to Russell Perkin’s RE: “Beyond Suspicion”:

The Fusion of Text and Reader and Guilty Pleasures:

As for the fusion of text and reader, Frye speaks of this fusion in Words with Power: to paraphrase, just by reading, we are resurrecting from the past into the present, the work, the speaking voice, in the site of the reader. The centre of the logos is in the reader, not under the text, and changes place with the Logos at the circumference which encloses both.

Existential Projection: Frye noted in The Practical Imagination that it is difficult to read from the point of view of an evil character. Put another way, our reading habits/personal ideology, will not allow us to become in Iser’s phrase, the ideal reader in a work like American Psycho, to walk in that character’s shoes so to speak. Coming from the other direction, one of my guilty pleasures is a song by Nine Inch Nails which I enjoy, but then my ideology/reading habits and superego come in to censor my id, to cancel that enjoyment. It’s a cognitive dissonance not unlike eating something you are not supposed to.

Should we just trust the imagination when we merge with the text to protect us and pull us out after our reading?

In response to Joe Adamson’s The Social Function of Literature:

The Authority of Literature and the Arts:

Short Answer: Literature shows us the world we want (comedy and quest romance) and the world we don’t want (tragedy, irony, satire).

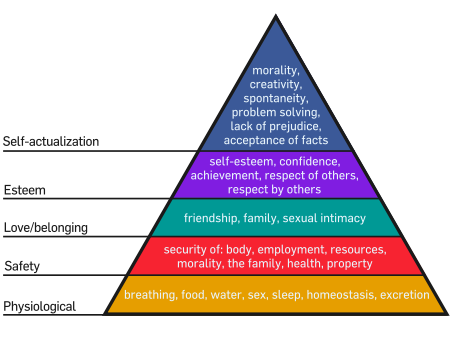

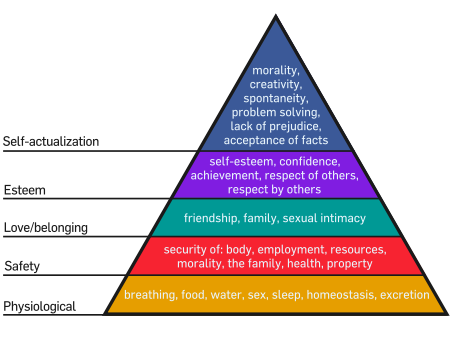

Long Answer: At the risk of sounding glib, for my younger students who could not read Words with Power or understand primary and secondary concerns, I point to Abram Maslow’s needs of life. The authority of literature is to remind us of the needs for life. Every story shows these needs either being fulfilled or denied/subordinated. Usually my students watch their favourite movie and report on the following checklist whether these needs are fulfilled or denied.

1. Physical Needs (movement, food/air/water, reproduction/family, clothing, shelter, property, technology and money).

2. Safety

3. Love/Belonging

4. Self-Esteem

5. Cognitive needs (need to know)

6. Aesthetic needs (need for beauty/art)

7. Humour/Optimism

8. Self-Actualization (power to help oneself)

9 Transcendence (power to help others).

I once had a parent angry that I screened the Eminem movie 8 Mile (13 kilometres in Canada), saying it was crap. After giving her the list, she understood what art does as a whole, even popular art.

As Frye says, his ideas are for the average 15 or 19 year old. A vision of heaven, anagogy, should be open to anyone with a imagination.

The interesting thing is that Maslow’s Needs are most often taught in high school marketing/business courses to brainwash the public.

It’s time that literature reclaimed the imagination, showing how advertising is applying literature’s disinterested vision of an ideal world.

[Eminem’s Lose Yourself after the break.]

Continue reading →