A Summary of The Secular Scripture: the following is a revised and expanded version of the summary published in the introduction to The Secular Scripture and Other Writings on Critical Theory, 1976-991. Volume 18 of Collected Works of Northrop Frye. Edited by Joseph Adamson and Jean Wilson. University of Toronto Press © 2005.

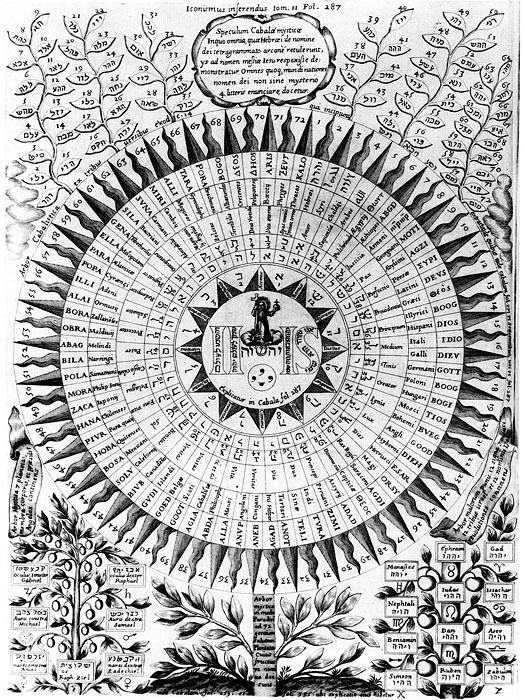

The Secular Scripture: A Study of the Structure of Romance was originally delivered in April 1975 as a series of lectures during Frye’s term as Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University. The occasion spurred Frye to develop more extensively his thoughts about romance as a literary form, a subject already central to the four essays in Anatomy of Criticism. At the end of his discussion of archetypal criticism in the second essay of that book, he observes that “archetypes are most easily studied in highly conventionalized literature: that is, for the most part, naive, primitive, and popular literature,” and he suggests “the possibility of extending the kind of comparative and morphological study now made of folk tales and ballads into the rest of literature” (104). In NB 56, one of the “Secular Scripture” notebooks, he remarks that after searching for some time for “a unified theme,” he now has “the main structure of a book [he has] been ambitious to write for at least twenty years, without understanding what it was, except in bits and pieces” (par. 157). His hope is to “make it the subject of [the lectures] at Harvard. After all, it’s fundamentally an expansion of the paper I did for the Harvard myth conference.” The latter paper, “Myth, Fiction, and Displacement” (FI, 21-38), outlines and develops a “central principle about ‘myth criticism’: that myth is a structural element in literature because literature as a whole is a ‘displaced’ mythology” (FI, 1).

The Secular Scripture explores three related areas of thought that will continue to preoccupy Frye: the dialectical polarization of imagery into desirable and abhorrent worlds; the recovery of myth in the act of literary recreation; and the struggle and complementarity between secular and sacred scriptures, between human words and the word of God.

The specific subject of The Secular Scripture is the study of sentimental romance, the literary development of the formulas found in the oral culture of the folk tale. It first appears in European literature in the Greek and Latin romances of the early common era. As a central form it surfaces again in the medieval romances and in the Elizabethan reworkings of the conventions of Greek romance, reemerging in the Gothic novels of the eighteenth century, and forming the structural basis of a great variety of nineteenth-century prose fiction, most explicitly in writers such as Walter Scott, Edgar Allan Poe, and William Morris.

In the twentieth century and beyond it appears again most unabashedly in fantasy and science fiction. Recent examples of the recurrent appeal of romance can be seen in the long-term success of the Star Wars films, the spectacular popularity of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels (and films), and the renewed interest in the cinematic version of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, as well as in the widespread appeal of mystery novels, crime fiction, and Gothic horror fiction and “thrillers,” not to mention the remarkable pervasiveness of all these forms of romance in current film and television.

Frye observes that the forms of storytelling peculiar to saga, legend, and folk tale do not differ essentially from those of the Bible and certain other texts–the “epic of the creator”–which have had a sacred circle drawn around them by religious and cultural authority. The distinction between sacred and secular scriptures, as far as Frye is concerned, is primarily one of social context. Sentimental romance–the “epic of the creature”–has been vilified for centuries by the established cultural tradition, largely because of its unsanctioned preoccupation with sex and violence, and the disapproval of such “proletarian” or popular forms holds even today. Even when they become privileged objects of study, as is currently the case in cultural and film studies, the interest is often largely confined to their hidden ideological imperatives–what they tell us to believe or do.

The term “popular culture” has a widespread currency today, and its definition is often disputed. Frye offers what appears to be a very simple definition, at least of its literary form. It is that area of verbal culture–ballads, folk tales, and folk songs, for instance–which requires for its appreciation minimal expertise and education, and is therefore available to the widest possible audience. At the same time, by virtue of its wide-ranging appeal, popular literature often points the way to future literary developments, for with the exhaustion of a literary tradition there is often a return to primitive formulas, as was the case with Greek romance and the Gothic novel. Frye does not imply any value judgment in distinguishing popular from elite culture. He insists, instead, that they are both ultimately two aspects of the same “human compulsion to create in the face of chaos.”

Continue reading →