Here is my letter to the editor yesterday regarding the Centre for Comparative Literature

Dear Editor,

I have not seen the Gertler report with its recommendation to close the Centre for Comparative Literature at the U of T and to fold it (what would be left of it) into a School that would also include the five departments of Italian, German, East Asian Studies, Slavic languages and Spanish and Portuguese. As a university scholar/teacher and a university administrator, I saw firsthand what precedes and follows such decisions.

Because each individual language and literature department is a linguistic minority in an English-language university, its very existence depends on unusual professional commitment and hard work. It also depends on its ability to convince budget officers that when you fold the cultural milieu of a language and literature department into a broader English-speaking mix, you destroy the identity of the original, and much of its reason for being. The professors no longer use the identifying language in most of their daily work, the staff have to function mainly in English, and the language context in which students are meant to become proficient ceases to exist.

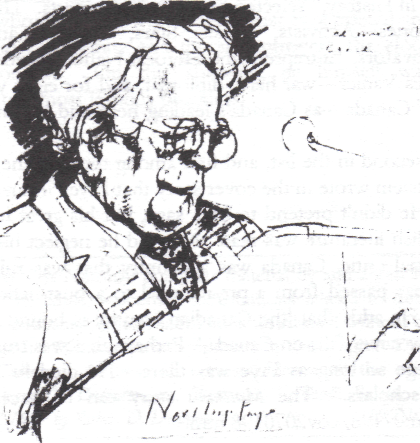

The paramount strength of the graduate programs in the Centre for Comparative Literature has been its ability to attract, for work at an advanced level, able students from around the world who have had deep exposure while undergraduates to more than one language and literature in at least two of the kind of department that would disappear into the proposed new School. There is a close symbiotic relation between the U of T Centre and the separate language and literature departments at the U of T and the other universities from which the students come. As the Northrop Frye Professor of Literary Theory in the Centre in 1991-2, I saw this fact in every class discussion: the accuracy and incisiveness of what a young scholar says about a literary text is convincing only when the text is being read in its original language. It is an important part of Frye’s legacy that he knew this and that he championed the need for just the kind of intellectual and imaginative work that the U of T Centre has been doing for 41 years.

Sincerely

Alvin A. Lee

Professor of English Emeritus and President Emeritus, McMaster University

General Editor, The Collected Works of Northrop Frye, 30 vols (University of Toronto Press)