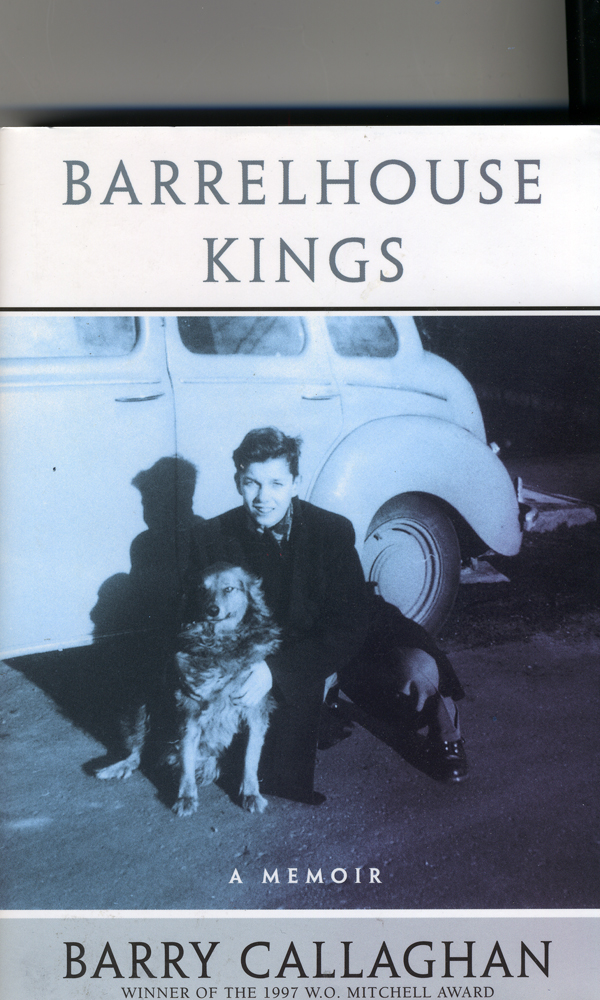

Lest this blog get too serious, here’s a little episode from Barry Callaghan, Barrelhouse Kings (Toronto: MacArthur and Co., 1998), pp. 551–7. [The ellipses are Callaghan’s.] A briefer account of the Frye/Gale episode is recorded in an interview with Callaghan by Roger B. Mason in Books in Canada 22, no. 5 (July 1993).

The supper to launch A Wild Old Man on the Road –– a story about two writers, a meditation on the nature of celebrity, youth and age, fathers and sons, betrayal and love— was given at George Guernon’s Le Bistingo by General Publishing, his new house headed by my old friend and first publisher, Nelson Doucet. There were some seventy people there . . . the one writer in the country that Morley [Barry’s father] truly admired and felt affection for — Alice Munro — and the premier, David Peterson, and Zachary flew in from Saratoga, and Peter Gzowski and Greg Gatenby, Robert Fulford and Northrop Frye all had a chair. In charge of chairs, I had mischievously put the actress Gale Garnett beside Frye on a banquette. The great scholar, whose public manner was often “shy reluctance” (masking an enthusiasm for the scatological), eyed her ample cleavage. People kept interrupting with “Good evening, Doctor Frye” and “Very pleased, Doctor Frye,” until Gale—a forthright literate woman of gumption, beauty and wit, a trouper in the finest sense (schooled as a girl by John Huston, a star in Hair, a companion to Pierre Trudeau, a journalist for The Village Voice, novelist and a mature actress in fine movies, including Mr. and Mrs. Bridge), said, “Doesn’t anyone ever talk to you like a human being?”

“Not often,” Frye said.

“I’ve a cure for that,” she said, taking two red sponge balls out of her purse. She squeezed one, it opened, and she clamped it on his nose. She damped the other on her own nose and the two sat side-by-side beaming, clowns on a banquette.

A film producer from Amsterdam cried, “Norrie, how are you?” Frye stood up and clasped his hands, saying, “Fine, fine.” Gale handed out a half-dozen clown’s noses and soon Greg Gatenby and Francesca Valente, director of the Istituto Italiano, and Premier Peterson were posing with Frye for snapshots, all clowning, happily wearing red noses.

Frye, sporting a red nose, was strange, but Frye partying among us was more than strange. In graduate school, I had avoided him; I’d thought I smelled the manse on him, the Presbyterian manse.

Then, in the early sixties, when Edmund Wilson wrote that many of Morley’s “compatriots seemed incapable of believing that a writer whose work may be mentioned without absurdity in association with Chekhov’s and Turgenev’s can possibly be functioning in Toronto”— the last to come forward and affirm Wilson’s judgment, as far as Morley was concerned, was Northrop Frye. In his roman a clef, A Fine and Private Place, he savaged Frye, in the figure of Dr. Morton Hyland.

A few years had passed and I published The Hogg Poems. To my astonishment, Frye wrote me enthusiastically about the work and when my second book of poems, As Close as We Came, appeared in 1982, he offered a fine prose response for use on the book jacket. When we met, he told me how much he admired The Black Queen Stories and then said, “How is Morley, he’s been having quite a burst, fucking wonderful?” I nearly fell out of my tree. But when I told Morley that I had been with Frye, he surprised me, too, saying, “How’s he holding up, his wife has Alzheimer’s, it must be awfully hard on him, all the things he has to say, and no mind or memory in her to hear it. Awfully lonely.”

On a Sunday at noon, Claire and I hosted a brunch at 69 Sullivan: Alberto Moravia, Northrop Frye, Morley, the French writer Alain Elkann, Greg Gatenby and Francesca Valente. This was the first time Morley and Frye had found themselves together since the publication of A Fine and Private Place. It was astonishing. Frye was shy but not in retreat, self-deprecating but only so that he could be in quiet command of his space. Morley — who could be feisty — as he talked, kept sweeping his arm toward Frye, like a courtier, as if he wanted to make sure that Moravia, a fellow novelist, would take the unassuming critic seriously, and when it came time to sit down, Morley actually drew Frye’s chair back, gallantly, as if he were the host (of course, one has always to be suspicious of gallantry: is it an admission of superiority or a gesture of disdain, or the blend of both?). It was hilarious and touching and grew more so as the three great men began to quietly explain the world to each other, offering little insights, playful and provocative observations— three heavyweights flicking ideas like nimble featherweights, tap tap, jab jab, until Morley got around to Sophia Loren and — as Morley explained that the mystery of her beautiful face was that everything in it was wrong — Frye made a loud sensual umming sound. “The eyes are too far apart, the nose is too big, the mouth too big,” Morley said, “yet she is beautiful, she is her own perfection,” and Moravia, who had a perky light in his old eyes, said, “Si, Si, so much for Botticelli. . . .” and they laughed loudly as if they had just exchanged an insight on behalf of a beauty that was sensual in all its surprising irregularities, irregularities that had their own harmony . . . and Morley started in on one of his favorite notions: “I’ve been watching all those nature films on television, down deep in the Amazon, all that insect and animal stuff . . . and I’ve been fascinated to see the way a bug can’t be anything other than the bug he was meant to be, living only to realize the beauty of its own form, the form — whatever it is — emerging out of itself, completing itself, whether it’s a butterfly or Sophia Loren.”

“And this is why,” Moravia said, “Michelangelo’s last Pietá is so great, it is like watching a butterfly emerge out of the stone,” and Frye said, “But this is all I ever meant by archetypes. There are forms, they are in us, they emerge . . . we become who we are.”

“And with all our everyday exercise of the will,” Morley said, “we become who we were meant to be, freely.”

“Of course,” Frye said.

“Well, now. . .” and they paused for dessert.

Within a year, Frye’s wife died.

On several occasions, Claire and I were invited to Branko Gorjup’s and Francesca Valente’s flat to have supper with the lonely old scholar. I picked him up at his house, the rooms all in darkness as he got into his coat or looked for an umbrella. It seemed he was going to live out his life as a solitary man. But then he astonished everyone. He got married, and was quoted in the papers as saying that he’d known Elizabeth since college days when they had dated, but then they had each married, and so it was not until both their spouses were dead that they could get together again, to marry. He had taken her to a hotel in the small town of St. Mary’s where they had had their last college date and he had proposed.

When I saw him next I said, “You old coot.”

He smiled shyly, tucking his head into his shoulder as he often did and said quietly, “Fucking right.”

It was clear: as a wise-acre student I couldn’t have been more wrong: my man from the manse had a quiet liking for four-letter words—and women.

Branko and Francesca held a small post-wedding supper for the couple. What, I wondered, could Claire and I give to elderly newlyweds. I asked Morley. “A truss,” he said, and went off giggling into his kitchen. “Helpful,” I cried, “always helpful, that’s what I like about you.”

He came back carrying a cup of watery instant coffee and said, “Give him what Jack McClelland gave me on my 80th birthday.”

“What’s that?”

“A year’s subscription to Playboy.”

“Jesus, you’re kidding.” “How could I kid about that?”

In an antique store I found an inlaid and laminated wood kaleidoscope. “For the visionary critic,” I said triumphantly, and then couldn’t believe my good luck as I picked up a scale-model toy refrigerator from the fifties . . . the motor on the back being a roll of scotch tape, and inside, the eggs were tiny erasers, the steak filets were tiny red marking stickers . . .

Before supper, the gifts were opened. Frye allowed himself a cursory look through the kaleidoscope and reached for the refrigerator. He opened the little door. His face lit up as he spilled the contents into his lap. He took the motor off, put it back. He rubbed an egg-eraser on his wrist as Elizabeth peered through the kaleidoscope, crying, “Oh, look at this. Look.”

“Haw,” he said, pressing a little red sticker to the nail of his forefinger. “Looks like sirloin to me.” We toasted the couple with champagne and Branko called us to table. Frye, on the sofa, did not move, engrossed in trying to get all the pieces back into the refrigerator. In the entrance to the dining room we stood watching him. He knew we were watching him, waiting. Francesca, in this gap of silence, said, “We should make another very important toast.” She explained that the University of Bologna, the oldest university in Europe, about to celebrate nine hundred years, was going to mark that celebration in the spring by giving an honorary degree to Frye. “This is something very special,” she said, lifting her glass. Frye lifted his head, smiled, and all the eraser eggs fell out of the refrigerator into his lap.

Frye went to Bologna with his new wife. I had coffee and biscuits with them there the day after he received his honorary degree. He and his bride were very happy and he chattered to her the whole time. They went off like honey-mooners to Venice. Within the year, she, too, was stricken with Alzheimer’s.

We were asked to rise for a toast at Le Bistingo — Frye and Gale were wearing the red noses again — and we raised a glass to Morley: “To the wild old man,” Nelson Doucet, his new publisher, said, “who is still on the road.” (When Morley had finished the manuscript for this novel, I found myself conducting a three-way bidding war for the book: Lester & Orpen Dennys, General Publishing and Macmillan, who were trying to buy him back. Morley signed for almost five times more advance money than he had received in Canada before, and I loved the idea that such bidding was rooted in a matter of drinks and biscuits in the Park Plaza Hotel.) Alice Munro took off a long silk scarf and looped it loosely around Morley’s neck and kissed him firmly on the cheek. Commissioned by Doucet, my son Michael had painted the book-jacket’s image of a wild old man on a pink sweatshirt. Morley gave the sweatshirt to Munro who put it on to applause. It was a playful folderol scene . . . Frye wearing his red clown’s nose, Morley wreathed in a long ladies scarf, Munro, breast emblazoned by a wild old man going down the road, and Morley, holding his cane like a hockey player holds a stick when he’s about to cross-check another skater into the boards, stood up as a young writer cried, “What do you make of all this, Morley?” “Nothing.”

“Come on, you never make nothing out of anything.” “There are many, many many eyes,” he said, “like all the eyes on Egyptian tombs and many many people in this world and a thousand ways of looking at things, at life, and everyone should look at life and try and see it for themselves, as their own.” He was about to sit down but then he kept on, liking what he had to say, and so did I because I’d heard him say it before: “A man who has no view, who sees no relationships or no value to relationships, that means he has no way of identifying the fact that he’s ever been in this world. He didn’t make anything out of it. What a terrible thing, to have been dumped on your rusty-dusty in this world for seventy or eighty years and then to come out of this world and somebody sitting outside the Pearly Gates says, ‘My boy, what do you make of this, the world?’ and you say, ‘Nothing.’

“So what do you make of this?” “I told you, nothing.”

To great laughter, he gestured toward Munro and recited like a schoolboy:

May weep, but never see,

The night of memories and of sighs

I consecrate to thee.

His mother would have been proud.

At the evening’s end, Frye — shuffling up to Morley’s side at the front door of the bistro — holding his red nose in his left hand and smirking, slipped his arm under mine, saying, “Great girl that Gale.”