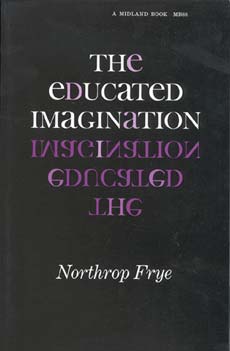

With the school year beginning, a lot of students out there will be encountering Frye for the first time, and The Educated Imagination is likely to be their first encounter. Here, therefore, is a study guide and some questions for them to consider as they read.

The spatial or schematic form of chapter 1:

Levels of Mind

1. (Theoria or dianoia) Speculative or contemplative: one’s mind is set over against nature. Separating, splitting, or analytic tendency: me vs. not me; intellect vs. emotions; art vs. science.

2. (Praxis) Social participation: motivated by desire (one wants a better world); intellect and emotions now united; necessity (work what one has to do); adapting to environment; transforming nature.

3. (Poesis) Vision and imagination: also motivated by desire but here it’s a desire to bring a social human form into existence, i.e., civilization; freedom.

Corresponding Levels of Language

1. Language of consciousness or awareness; the language of nouns and adjectives. Language of thinking.

2. Language of practical sense and skills (work, technology); language of teachers, preachers, advertisers, lawyers, scientists, journalists, etc.); language of necessity. Language of action.

3. Language that unites consciousness (level 1) with practical skill (level 2); language of imagination; literary language; language of freedom. Language of construction.

Attitudes

1. Awareness that separates one from the rest of the world

2. Practical attitude of creating a human way of life in the world.

3. Imaginative attitude or vision of world as imagined or desired.

Chapter 1, “The Motive for Metaphor” (phrase from title of a Wallace Stevens poem)

1. What are the two points—one simple and one complex—Frye makes in connection with the relevance of literature for today (pp. 16ff.)?

2. What is the motive for metaphor?

3. What does Frye mean by “a world completely absorbed and possessed by the human mind”?

4. What does Frye mean my transforming nature into “something with a human shape”? What does he mean by “the human form of nature,” which he seems to say is the same thing as “the form of human nature.”

Continue reading →