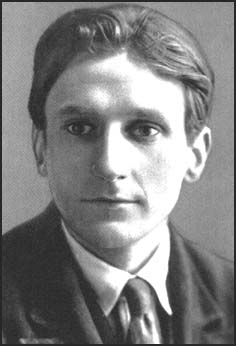

Undertones of War, the book that Helen Kemp picked up––Edmund Blunden’s autobiography of his traumatic WWI experience––has recently been reissued by the University of Chicago Press. It includes a selection of Blunden’s war poems. Readers of Ward McBurney’s terrific poem might be interested in two letters to Frye from Blunden, spurred by Frye’s having sent his Oxford tutor a copy of Fearful Symmetry. During his second year at Oxford, Frye had been urged by Blunden to postpone the writing of his Blake thesis and concentrate on the “schools” – the examinations for his degree.

c/o Times, Printing House Square, London, E.C.4.

6 Novr. 1947. With great pleasure I received the book this morning, and with perplexity––for I leave today with family for Japan and am in the same old Christmas tree condition as when once in the Elder War we were about to move . . . . I think that I will have the book kept safely for my return when I can sit down to it with the necessary library in reach and then I’ll write you a proper letter of thanks. You will know I still recall vividly yr. devotion to Blake at Oxford and I rejoice in the spectacle of such constancy of imaginative endeavour––in these days of rapid zests and desertions. We all read Miss Sitwell’s first eloquent appreciation of the Blake [Edith Sitwell, “William Blake,” Spectator 179 (10 October 1947): 466] which must have been a most welcome press cutting. I’ve been away from T.L.S. latterly but know that a review is in hand there. [“Elucidation of Blake” by an anonymous reviewer appeared in TLS, 10 January 1948: 25] Hope you are well and merry. Merton is unchanged in much, but men come & go: you will have heard that H.W. Garrod, who seems the exception, has had his portrait done by R. Moynihan for the panelled room where you attended Collections. It’s a speaking likeness, & a work of art. [Garrod, a classics scholar, was a fellow at Merton College for more than sixty years.] Every good wish, & thanks indeed. EBlunden.