A memoir of Blake, Frye and the 60s from Bob Rodgers. Bob is a former grad student of Frye’s who became a documentary filmmaker.

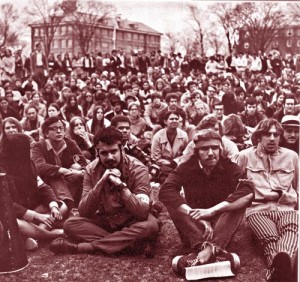

When I set out for university my motives were not entirely laudable. Movies about universities made their social life look appealing and I wanted a way out of Flin Flon anyway. Also, in the 1950s, if you managed to scrape through matriculation with a B average university was just something you did. Tuition was cheap, summer jobs plentiful and lucrative, so why not? What friends who had gone before me said was: “Don’t take Science or Engineering. They’re hard. Take Arts”.

By second year I was having a splendid time. I played basketball for the University of Manitoba Bisons and endless hands of Bridge in the student union cafeteria. I got fake ID so I could drink at the Pembina beer parlor. I went to movie previews on Academy Road every Thursday, and to curling bees and dances on weekends, and there was a whole residence of pretty girls to date so long as you got them in by eleven. In all of these things I don’t remember being much different from anyone else I knew in Arts.

With one exception. One fellow called Lennie who sat beside me in my poetry course was unlike my basketball friends and my home town friends. He was a Ukrainian from the mysterious “North End”, a section of Winnipeg beyond the CPR tracks that was as foreign to me as Bukovina. If a professor assigned a library book and you got round to looking it up it was always gone. I’d find out later Lennie had it.

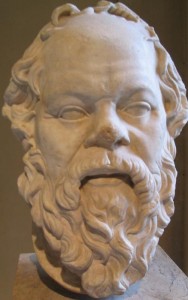

Sitting in the cafeteria one day Lennie said: “What do you make of William Blake?” I was circumspect. I remembered reading “The Tyger”, “Ah! Sunflower”, and “The Chimney Sweep” in High School, and we had all grown up singing Blake’s “Jerusalem”on occasions of patriotic fervor for the British Empire. I wasn’t ready to admit to him that I had been trying to read Blake’s epic poem, ‘Jerusalem’, and found it impenetrable. He pushed the book he’d been reading toward me and went for coffee refills. It was The Collected Works of William Blake, the Keynes edition of 1956. He knew I fancied Milton, which he didn’t. He left a page open where I read: “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.” I read the lines several times, trying to figure out what Blake was saying.

My new friend returned with coffee and sat watching as I skipped through the passages he had flagged in the Marriage of Heaven and Hell section.

Exuberance is beauty. (I liked that idea. For the same reason I preferred Anthony to Octavius.)

How do you know but evr’y bird that cuts the airy way is an immense world of delight, clos’d by your senses five? (That was the one I couldn’t get my head around at all.)

The cistern contains: the fountain overflows. (Same thing.)

The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom. (Whoa there. I was learning about excess in my extra-curricular activities, and thought it more likely they led in the opposite direction.)

What is now proved was once only imagined. (Well all right. So you don’t invent or discover anything without having imagination.)

The cut worm forgives the plough. (Is that what they meant when they said you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs? Not exactly. A worm isn’t like an egg and a plough isn’t like an omelette.)

Better murder an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires. (That was an unsettling one. Like some Nietzsche things I’d been reading it sounded dangerous.)

Continue reading →