A couple of responses to Joe’s earlier post:

Russell Perkin:

Joe, I find very little to disagree with in what you have written here. (And I especially share your enthusiasm for Mill. I teach On Liberty whenever I get the opportunity). Ultimately I think it comes down to a question of temperament: didn’t Frye somewhere describe himself as an Odyssey-critic, inclined towards romance and comedy as opposed to tragedy? I must be too inclined to pessimism!

I agree with you about not subordinating works to ideological criticism. The work, the author, not the student, and not the teacher, should be the voice that is heard in the classroom. But the nagging point that Bogdan raises for me is that, to quote her again “the hypothetical dimension of literature notwithstanding, literature does say things.” It doesn’t entirely leave behind what Frye calls “the original reference,” though of course it cannot be reduced to that either.

Adam Bradley:

Joe has hit on what I believe is the real problem with critical theory; that the logical end point of ideological criticism is a disdain for literature. How can it not be so? Identifying power structures a la Foucault or searching for Marxist class inequalities inevitably leads to an identification of the problems inherent in a text. Apply this model enough times to a text from enough ideological views and what is left? This to me is the number one argument against this type of inductive criticism. If I begin with an ideology and then use the tenets of that philosophy as a lens through which to see a text, then not only will I inevitably see whatever I’m looking for but it will also eventually become the reality of that text. If this is misogyny or anti-semitism or some other disdainful ethos, then it becomes a necessary action to dismiss that text as being “only” of that ethos. I have always wondered if this is a conscious act or simply a necessary outcome of such an approach. Regardless of the answer to that question or whether critics admit to this practice, the necessary result is that the text ends up becoming a secondary object to the soapbox that the critic puts himself on, yelling to the crowd about how terrible that text is. It reminds me of how the religious right creates demons out of everything to further the cause. By identifying everyone else as being evil then they can laud their own practices as being holy. I believe that critical theory began with good intentions but has ended up being the right wing faction of literary criticism, the bullying older brother that finds whatever he is looking for and shouts about it.

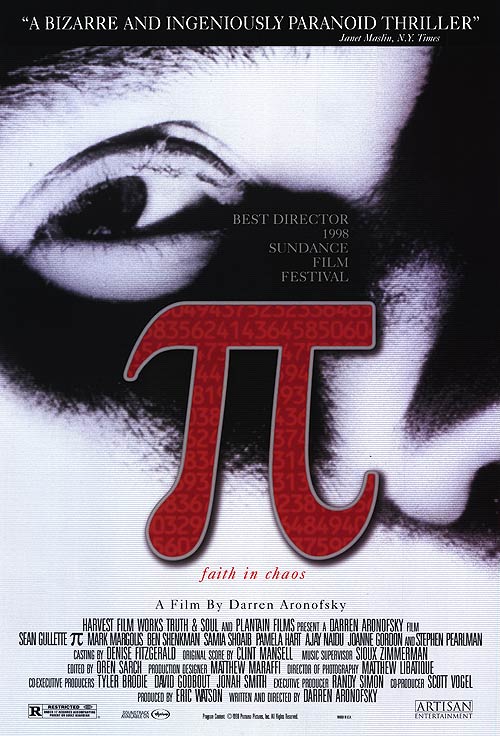

There is a speech in the movie Pi, directed by Darren Aronofsky, where the aged professor tells his genius student that if you spend all of your time looking to find a certain number or type of construct that you will begin to see it everywhere in nature, the world will bend to your lens: 56 steps up to the library, 56 petals on a sunflower, 56 seconds for the elevator to arrive. If you look at the world from a designated view, the world will present itself to you from within that view. The issue is very important to literary studies: you will find whatever you are looking for if you look hard enough. Apply this to a text and, before you know it, it is the critic who is overlaying assumptions on that text and the soul of a work of art has been lost. This ‘loss of soul’ occurs at the moment when the critic preaches to the text instead of listening to it. It is the moment that they think of the text as a right not a privilege; it is the moment that they force themselves into the pages instead of letting the pages reach out to them. It is this act that makes me wonder if literary critics actually even like literature.

These questions apply to all of us. Do you remember when you first read something that really moved you? Do you still get twisted up inside when you re-read that work that first made you want to spend your working life within the pages of books or in a classroom? I ask this of all of you: this is not simply a question for the critical theorists. Do you still like poetry or has it simply become work? Does the ideology you apply — because even Frye’s notions on some level are ideologies — allow you the room to enjoy literature? Do you still get moved? I can say that it was first Joyce and then Beckett who changed my life when I was sixteen years old. I had no idea that you were even allowed to destroy the lives of your characters as Joyce did in ‘The Dead’, or question the existence of Godot. When I read these words for the first time my world was forever changed. This is the power of words we so often forget. We criticize, we speculate and we write but do we still let ourselves fall in love with words? I can say with a certainty that the types of ideological approaches that critical theory employs will inevitably lead to a hatred of literature, but is ours any better? One of the things that I take from Frye is that by understanding the underlying structure of literature we can suspend our ideological judgments and primarily ‘love the book’. Only after we experience this wonder do we criticize. Critical Theory seems to skip this step, but it is a slippery slope and if we don’t stop and wonder at the sublimity of words then we will travel the same path. The paradox of this situation is that I believe the critic can create in the same way that the artist does, that the critic himself can inspire wonder. But before he can do this he must look on in the wonder himself and then refer to a framework from which he can explain it to others. This to me is what Frye was trying to create, the Framework that a critic can use to describe his wonder. So for people to say they have ‘no time for Frye’, which a former professor of mine told me once, seems simply absurd until you realize that the critical theory had made him lose his love. That the inevitable path critical theory forced him to take was to end up hating the thing he was supposed to revere. This contradiction is why I believe critical theory to be flawed and is why I believe the critical theorists are so forceful with their craft. I believe it is the job and the responsibility of the critic to convey the wonder of words to everyone else, and how can this be accomplished if we don’t first sit and wonder.