1942:

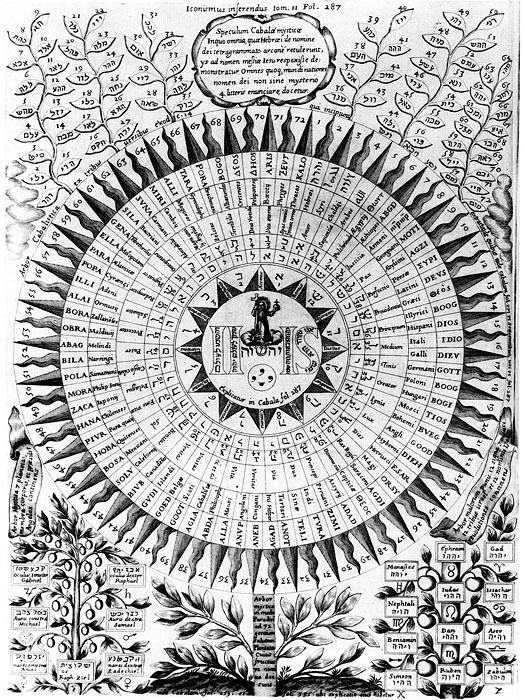

[130] Well, today was the Retreat. I got through it somehow, dividing it into “The Search for Wisdom” (morning) and “The Search for the Word” (afternoon). I said everything is learned by the scientific method and absorbed in the personality as an art, a knack or flair. The former is knowledge, the latter wisdom & the goal of an “arts” course. Knowledge of itself is lumber or a machine: a liberal education implies the elimination of pedantry & vulgarity & the achievement of a fully integrated personality. Students come to college because they want to grow. Mental growth is a fact like physical growth. But the possessor of a liberal education is not his own end, nor do his class affiliations or social responsibilities exhaust his duties, for there are no douanes in culture. Hence wisdom is the entry into a universal order and a world of spiritual values. The discussion was good but the staff talked too much. I stressed “scientia,” knowledge, as against “love of wisdom,” philosophy, which defines defines the human attitude towards the knowledge. Love today is interest, the difference between the good & mediocre student of equal intelligence. In the afternoon I went on with “The Search for the Word”: wisdom reveals spiritual values but does not save more than a few Stoics of exceptional strength who have the very rare quality of heroic wisdom from an evil physical world. Besides, the personal is superior to the impersonal. Hence wisdom becomes less an abstract noun & more a concrete entity of mind, or person: a saviour, furthermore, a God also man. Hence wisdom which arrives at the Logos has expanded into revelation or vision. The kids couldn’t get that, of course, and fought whether you could know if God exists or not. However, I really think the Retreat was less hideously futile than usual.