Here is Clayton Chrusch’s summary of the second chapter of Fearful Symmetry. (His summary of chapter one can be found here):

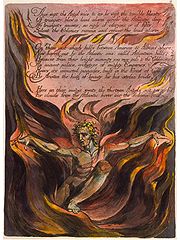

Fearful Symmetry Chapter Two: The Rising God

Man is All Imagination. God is Man & exists in us & we in him.

1. God is the fully developed human imagination.

This chapter presents Blake’s theology. His theology is based on the identity of God with humanity and in particular with the fully developed human imagination. God must be human because we cannot perceive anything greater than human. Since existence is perception, nothing superhuman can exist. Furthermore, the fact that Jesus was fully God and fully man means that God posseses no attributes which are not human.

We are God in our perceptions. No one can perceive God, but when we perceive the particular, we perceive as God. An egotistical perception sees a general reality, but a divine perception sees a particular reality. Blake calls the perception of a general reality experience, and the perception of a particular reality innocence.

What is true of perception is true of creation–when we create, we create as God. Frye writes, “all creators are contained in the Creator.” For Blake, worshipping God means honouring the creativity of human beings, and honouring most those with the most developed imaginations. The more people suppress their imaginations, the more they turn their backs on God, that is, their own divinity. But turning our backs on our divinity also means turning our backs on our humanity–it is what is great in us that makes us human, not what is small. God is the species, and humans are individuals of that species. God is the essence, and we are the identities arising from that essence. God is the body, and we are the limbs.

2. Against God as a designer

It’s wrong to look to Blake for an informed opinion of all things. There are some things that Blake was simply not interested in. He was not interested in mathematics, for instance, and though he may seem to disparage it, a sympathetic reader will realize that Blake is really attacking superstitious uses of mathematics. These include occult math, that is, numerology, and the kind of scientific reductionism that sees reality as merely an abstract mathematical design rather than the concrete mental creation that it is.

In some of Blake’s poems, Blake uses numbers and diagrams, but these are part of the imaginative unity of the poems and do not indicate “any affinity with mathematical mysticism.”

Blake could not bring himself to believe in a God that is a designer rather than a creator.

3. Against God as an impersonal and mechanical power

Blake dislikes Newton partly because of the kind of theology that Newton’s universe suggests. Such a vast universe governed by mechanical laws suggests a God that is a great impersonal and mechanical power. Such a theology would be further encouraged by the 19th century discovery of “the immense stretch of geological time, in which nothing particularly cheerful seems to have occurred.” Such a God is distasteful to Blake not only because it must be a tyrant, but because it reduces the whole universe and all of life to less than conscious activity.

Blake agrees with the followers of the Newtonian Gods that God is the essence of life. But the followers of Newtonian Gods discover the essence of life by abstracting life until they get to the simple idea of motion. This is the same lowest-common-denominator approach to discovering reality that Blake hates so much in Locke. Blake sees that, of all beings, humans are most alive and so the essence of life is found in human attributes such as intelligence, imagination, judgment, and conscious purpose. And so God must possess all these attributes.

As for evolution, a Blakean must interpret it not as a mechanical process of stimulus and response, and certainly not as intelligent design, but as an exuberant imaginative development in all possible directions.

Blake did not idealize nature and possessed no illusions about “noble savages” living in a state of nature. Nature is cruel, and anything living in a state of nature is savage. Nature achieves its highest form where both it and people are cultivated. For Blake, the central symbol of the imagination is a city, in other words, a world and a nature with a human form where the imagination “has developed and conquered rather than survived and ‘fitted.'”

4. Against an ineffable God, against an external God

So Blake rejects Gods that are superhuman designers or superhuman powers. Similarly, Blake rejects God that are superhumanly “perfect.” When Jesus says, “Be ye therefore perfect” [Matthew 5:48], he means we should fully develop our imaginations. Timid theologians think perfection means “pure” abstractions like “pure” goodness which, of course, can only be possessed by a purely abstract being, a complete non-entity that can only be described by negation: “infinite, inscrutable, incomprehensible.” Among other things, a purely good God is necessarily a nightmare of moral tyranny.

God is not superhuman in any way, rather he “does a Human Form Display/ To those who Dwell in Realms of day.”

At the beginning of Genesis, we encounter two different Gods, a more abstract one who establishes an abstract order, and a more human one who has human emotions and human inconsistency. The human one is still not what Blake means by God or Jesus means by Father, but he is much closer than the abstract one. Even a superhuman imagination or intelligence cannot be God. Whenever we try to conceive of something superhuman, we conceive of something subhuman.

Though “Blake often makes remarks implying an external spiritual agency,” for instance, when he speaks of artistic inspiration, but he means such remarks to be taken either ironically or as projection of some purpose that is actually a part of his own imagination.

Blake does not believe in a spirit distinct from the body, but does leave open the possibility that the imagination can take on a new form in a different plane of existence. Frye is cautious here about making any claims on Blake’s behalf about life after death.

5. Against any reverence for the established order

This is a difficult but important section of Fearful Symmetry, dealing with nature, the fallen and unfallen worlds, space, time, infinity, and eternity.

Because there is no divinity superior to ourselves, we do not need to accept anything as an unchanging fact of life. So we do not need to revere the established order, whether natural or social. Blake rejects natural law, for instance.

We must recognize that “nature is miserably cruel, wasteful, purposeless, chaotic, and half dead. It has no intelligence, no kindness, no love, and no innocence.” Of course humans are capable of even worse cruelty, but that is largely the result of human intelligence floundering in a subhuman world. Human beings are capable of wanting and imagining a much better world. As discussed in the previous chapter, not only is the world we desire better, but also more real. This leads us to the conclusion that the world we see is a fallen one, a bad imitation of the genuine article, a much better world. It is the work of the artist to recover this better world.

Since all reality is mental, and God is human, the fall is the simultaneous fall of the human mind, the physical world, and also a part of God. For Blake, the fall is the same event as the creation of the physical world.

The accomplishments of civilization show that human power is literally supernatural. Human beings in a state of nature are tiny vulnerable specks up against a huge, hostile cosmos, but this is a distortion of the true situation. The human creative power that can turn wild wolves into man’s best friend can transform the chaos of nature into an intelligible and responsive form–a human form. Frye writes, “As our imaginations expand the world takes on a growing humanity.”

But we should not mistake the unfallen world of innocence for a glorified children’s play ground. A human power that can transform nature is a Titanic power.

These Titans, or gigantic human bodies are, on close inspection, aggregates of many people. A country is such a larger human body, and we feel loyal to our country because we recognize that we are part of this larger body. The largest body we are part of, though, “is ultimately God, the totality of all imagination.” Blake calls this body Albion, who represents the unity of humanity. This unity was largely lost when Albion fell, which is why we experience ourselves as “separated, opaque scattered bodies.”

Blake rejects the conventional distinction between natural and revealed religion, where natural religion comes from human reason and revealed religion from God. This distinction is made because we insist on separating God from human beings. And we make this distinction because we want to invent some being (obviously not human) who is perfectly and abstractly good. Nevertheless, all religion of any value is revealed and comes from God. Still, God does not possess the purity we desire. For Blake religion, or revelation culminates in the Apocalypse, the Greek word for revelation, where all is revealed, all mystery vanishes. In that apocalyptic moment, we see clearly, we possess, not faith, but vision. Art trains us in this vision and so is the source of revelation. And the Bible, since it is “a unified vision of human life,” is therefore “the Great Code of Art.”

Locke’s approach of separating existence from perception has the effect of separating time from space. Time separated from space is clock time, “a mental nightmare like all other abstract ideas. An impalpable present vanishing between an irrevocable past and an unknown future.” Space separated from time is just as bad, a formless, indefinite extent that that can only contain an “unchanging order, symbolized by the invariable interrelations of mathematics.” When we dwell in abstraction, we live in these worlds, but these worlds have no place for the imagination which only exists in the real world of inseparable space-time, the eternal here and the eternal now.

To the imagination, space and time have a more definite shape. For Blake, the imaginative shape of time is defined by its imaginative boundaries: creation and apocalypse. Similarly space is imaginatively the body of a universal human being.

6. The four levels of the imagination

For Blake, there are four imaginative levels. The lowest is Ulro, a hell “of the isolated individual reflecting on his memories of perception and evolving generalizations and abstract ideas.” This is a world where the subject has turned in upon herself and excluded the objective world.

The next level is Generation, “a double world of subject and object, of organism and environment [….] No living thing is completely adjusted to this world except the plants, hence Blake usually speaks of it as vegetable.”

The third is the first truly imaginative world, the world that adds love and wonder to the world of subject and object and thus transforms the world into something lovely, delightful, paradisal. This is a world of lover and beloved instead of subject and object. Blake calls this world Beulah, which means married.

Beulah is truly a wonderful world, but it is not enough. In Beulah, we may see what is desirable, but we do not create it. We are still too passive. When we push through this world of lover and beloved to the world of creator and creature, then we have moved to the highest level which is Eden, symbolized not by a garden but by a fiery city.

7. Goodness only in the particular

What is good? It seems here that we cannot escape an abstract, objective answer rallying under one or both of the banners of truth and morality. But for Blake, the good, if it is to exist, can only be particular, and the particular is never exclusively objective.

The kind of divisions that are possible in abstract discourse are not possible in reality. And so “good” cannot be divided between truth and morality, nor can it be divided between truth, morality, and beauty, as it sometime is. The good is the whole, particular, indivisible experience in which truth and morality become real. An abstract goodness is no longer good.

Blake calls the experience of good, beauty. So Blake does not need any abstract aesthetic theory to describe beauty. Beauty, which is good, is pursued by imagination, “the Real Man,” and not by any part of the personality. The result of this pursuit is art, and ultimately civilization.

The development of science and morality is driven by an impersonalizing tendency. And yet science and morality are imaginative creations. This is only possible because there is a civilization, built up by the pursuit of beauty, which gives meaning and value to impersonalizing tendencies.

8. The fourfold God

Like human beings in their highest state, God, for Blake, is fourfold: “power, love, and wisdom contained within the unity of civilized imagination.” And this God is a human God, Jesus, in whose “risen body we find our being after we have outgrown” a childish dependence on a paternal God. In other words, “the final revelation of Christianity is, therefore, not that Jesus is God, but that God is Jesus,” that God is a human being with a human body and a human imagination. This being, body, and imagination are all aggregates of individual human beings, bodies, and imaginations.

There is a Creator and a Creation, and though religion will always try to give sanction to the fallen Creation, we will ultimately have to choose between them, and that choice between the Creator and the Creation is a choice between God and the devil. Choosing the Creator means choosing the “more abundant life in the larger human mind and body of God,” while choosing the Creature means “acceptance of the minimum life of nature and reason.”

This “cult of reason and nature” has always existed, but not until Blake’s time had it crystallized “into a dogmatic system with all loopholes for the imagination sealed off.” Frye here is referring to Deism, and suggests that Blake hated it not only for what it was, but what it would naturally become, which Blake calls Druidism, and which Frye hints is the Nazism and Fascism of his own time.

Fearful Symmetry was the very last of Frye’s major works that I read, and by the time I had first read it, I had re-read just about everything a few times over. I don’t know why I put off reading it for so long. I rationalized it as a youthful work (even though it was clearly not that), a mere precursor to Anatomy where the “real work” begins, and a study narrowly focused on a still somewhat obscure poet — an esoteric work, in effect. So, predictably enough, when I finally came to read it, it blew open all the doors and sent my carefully arranged mental furniture flying. It’s a book that still haunts and intimidates me, and I am generally very comfortable with Frye. Fearful Symmetry possesses all of Frye’s runic power to summon up the fearsome but benign power of the Magus/prophet: not, as he says elsewhere, the oppressive mystery that conceals, but the liberating mystery that reveals.

I am therefore very grateful that Clayton Chrusch has undertaken to provide us with a weekly summary, chapter by chapter. By the time I reach the end of each installment, I’m a little breathless with excitement. Such is the power of the book that Clayton’s lucid exposition effortlessly taps into it. I look forward to his next.

How is this the summary of chapter two? you only address his references to god, and not everything else he has to say.

Hi Jason. What do you think deserved more emphasis in my summary?