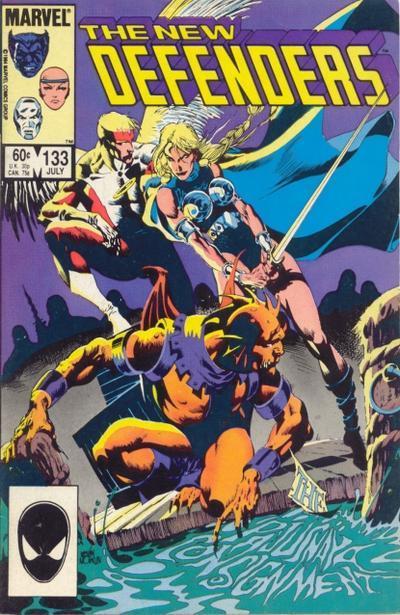

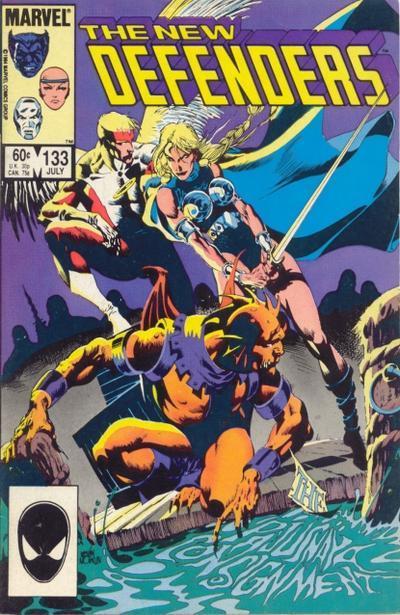

Frye appears in "The Pajusnaya Consignment" (above, July 1984) in Marvel's New Defenders series

In addition to Amis’s The Rachel Papers Frye has made his way into a number of poems, plays, novels, and discursive texts. An earlier post catalogued his appearance in contemporary poems. As for the other genres, one of the central characters of David Lodge’s Changing Places (1974) refers humorously to the perpetual motion of an elevator, “a profoundly poetic machine,” as symbolizing Frye’s theory of modes in Anatomy of Criticism (London: Seeker & Warburg, 1975; Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978), 212–13. Professor Kingfisher in Lodge’s Small World (1985), a sequel to Changing Places, is a fictionalized version of Frye. In Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water Dr. Joseph Hovaugh is modeled on Frye. Here are further examples:

• The following bit of dialogue occurs in Frederic Raphael’s play, Oxbridge Blues, from Oxbridge Blues and Other Plays for Television (London: BBC, 1984). Victor is a serious writer. Wendy is his wife:

Victor: I didn’t think you felt like discussing it.

Wendy: I don’t even know what “it” is. What is it? I know you’re ridiculously jealous of Pip and you can’t even bring yourself to accept his generosity without looking as though you’d much sooner be reading the collected works of — of — of — oh — Northrop Frye.

Victor: I would. Much. The Anatomy of Criticism, though flawed, was a seminal work in some ways. Why did you happen to choose that name?

Wendy: I wanted someone with a silly name.

Victor: I don’t find Northrop particular silly.

Wendy: Well I do. I find it very silly indeed. Not as silly as you’re being, but still very silly.

• From Gail Godwin’s The Odd Woman (New York: Knopf, 1974), 257–8:

Was Gabriel’s project quixotic? For almost two years, she had vacillated between thinking him a nearsighted fool and a farsighted genius. How could she tell? Surely there must be a way to measure it, but how? After the fact, it became a bit simpler. For instance, in the field of literature, of literary criticism, she knew Northrop Frye was a genius—even though some respectable scholars like Sonia Mark’s husband detested Northrop Frye. Frye’s ideas made sense; they rested on valuable hypotheses; they lit up the entire realm of literature for you. After you had read Frye, you thought of your favorite books as parts of a large family. You not only saw them as you had before, but you saw behind them and in front of them. It was like meeting someone, forming an opinion about this person, then being privileged to meet the person’s parents and grandparents, as well; and then being privileged to meet the person’s children, and grandchildren! Of course, someone like Max Covington would say, The person himself, alone, should be judged. What do parents have to do with it? What do his children have to do with it? They only confuse and diffuse you from the proper study of the object, which is: the object itself.

She had tried to lift her assurance about Frye—as one might gingerly try to lift an anchovy from its tin and place it, undamaged, on a plate—and transfer it toward her wavering confidence in Gabriel. Surely, during the forties and fifties when Frye was painstakingly filling his wife’s shoe boxes with notecards for Anatomy of Criticism, Mrs. Frye had had an occasional qualm. Or had she? After all, Frye had done Fearful Symmetry first. She had that to build on. She knew that her first closetful of shoeboxes had come to something. Whereas, with Gabriel, there was only the queer, eccentric little monograph, published half a lifetime ago!

Continue reading →