In response to Bob Denham’s post on how Frye thinks:

This is terrific, Bob. Well beyond what I could have hoped for. Here are some improvised thoughts in response:

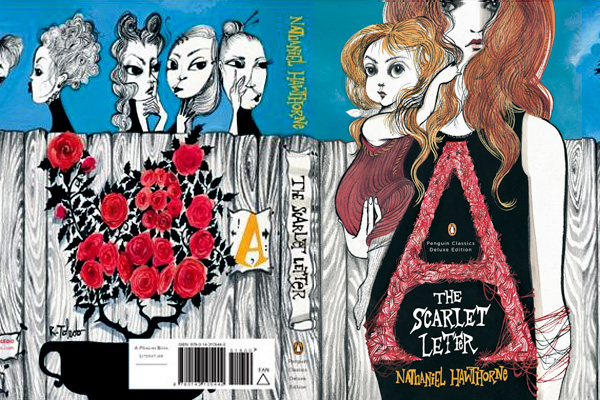

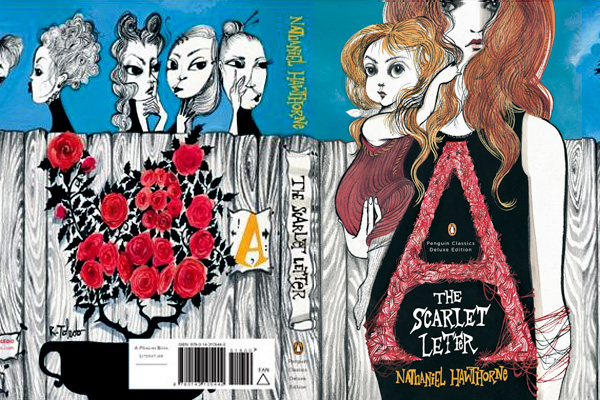

I was thinking in terms of practical criticism, in response to Michael Sinding’s question: how does an archetype in a given work, like an Ariadne’s thread, lead us into and all the way through a detailed critical reading of a text? At the time I was working on Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter: that is to say, I was teaching The Scarlet Letter–we’re now onto Melville, another overtly archetypal writer–and I was trying to use Hawthorne’s novel in my American literature class as an example of how archetypes guide our reading, indeed are of primary and central importance to the signifying power of the work.

In that novel (romance Frye would say), the opening chapter, which is simply a description of the prison door, hands the reader the keys to the two main blocks of apocalyptic and demonic archetypal imagery analogically organizing the meaning of the story. The central archetype of the novel, and of Hawthorne’s work in general, is the Eros or bride=garden archetype: it opens with the prison (and in the next chapter we get the associated image of the scaffold) and the rose-bush which is identified metaphorically with Nature (of the natura naturans variety) and sexuality, and is identified with Anne Hutchinson, and by association with Hester and with Pearl, Hester’s daughter, the latter grouping set in opposition to a patriarchal and morally repressive society that punishes sexual freedom and freedom of thought. Thus a deeply social and feminist reading of the novel is fully enabled by the archetypal reading, which inevitably leads to it, in fact, as a level of meaning sublated in the archetype. All of this and more, which I have only encapsulated here, is what the story unfolds when it is unpacked in detail just at the level of a structure of imagery, at the centre of which is, not the morally ambiguous image of the scarlet letter, but the image of the rose-bush.

The scarlet letter is a related image: the rose-bush is associated with a state of prelapsarian Nature and sexual love; the scarlet letter with the moral repression of sexuality after the fall and with the situation of woman under patriarchy as a scapegoat that carries the burden of shame and guilt for a repressed and projected sexuality. In this situation, the archetype reveals a further dimension, and the figure of Hester Prynne is a perfect example: “a dimension, ” as Frye puts in his discussion of the figure of Ruth in Words with Power “in which woman expands into a kind of proletariat, enduring, continuous, exploited humanity, awaiting emancipation in a hostile world: in short, an Israel eventually to be delivered from Egypt. ” Frye points out that “[t]he body-garden metaphor continues to be appropriate here, for nature is also exploited, fruitful, and patient.”

The critical process of such an unfolding through the archetype is dialectical, as you have shown in your post: but backwards or in reverse, since it begins with an unfolding of the archetype in which the other levels of meaning in the story are already sublated or aufhebened, if I may use such a term. That is what I meant by “follow the archetype.” Spotting it, of course, is the first step, but I am not talking at all about just “archetype spotting,” of which Frygians were, and I guess still are, accused of (and of which we had a rather hysterical outburst ourselves a while back on the blog).

I meant: follow the archetype, follow the damn thing: it will give you everything you need. Everything in the tale, even the most realistic details, are molded by the archetypal level of meaning. And the anagogic, which is where Frye’s dialectic ultimately takes us, and which you have unfolded above, is also implied in Hawthorne’s novel as what transcends or lies beyond the archetype in the story, the meta-archetypal, meta-literary level.

Archetypes are, semiotically speaking, recurring or inter-textual images “hyper-linked,” as it were, to a complex set of clustered associations. They are, I guess, what Michael Sinding would call particular types of imaginative or mythological frames that organize the way the reader makes connections and constructs the meaning of the text. The Great Doodle, then, would be the frame of frames.

I understand Clayton Chrusch’s unease with the term archetype. There are good reasons for it. But I prefer to embrace the term and reclaim its meaning: its usefulness, it seems to me, lies in the way it covers both metaphor and myth under one term, both story-shapes and structures of imagery, as outlined in essay three of the Anatomy.