Responding to Michael Sinding:

Thank you, Michael, for the recommendations in your last post. I have enjoyed reading Bérubé‘s blog, and I am planning to check out some of his books to get a better sense of his criticism. Some of the other names you mention I am much less enthusiastic about. My main objection to Said and Greenblatt, for example, is their want of intellectual integrity and honesty, which manifests itself in different ways. As my sometimes cryptic brother Al might say, it is something that makes me automatically distrust them (by the way, Al, I am still trying to figure out the point of your strange comment on Bob’s Don Harron post, and I’m not sure the smiley face helps). If Said and Greenblatt are examples of the best of the lot we are seriously in trouble. I tried to make my way through one of Greenblatt’s books once, but threw in the towel after forty pages. I felt there must be some point to what he was saying but it didn’t seem to be worth all the trouble he was taking to get there. I need to get paid for that kind of reading. Michael Happy puts it well when he alludes to the sense of entitlement that is constantly exuded in what is essentially rhetoric passing for argument: very little information and whole lot of glib and smart-sounding noise. As far as I can tell, the kind of narcissistic posturing that has been the norm over the last twenty-five years really only began to thrive with the critical theory boom: before then many of the people writing now and gaining celebrity for it would have been laughed out of the conference room. There was really a seismic shift in the intellectual standards of criticism and scholarship.

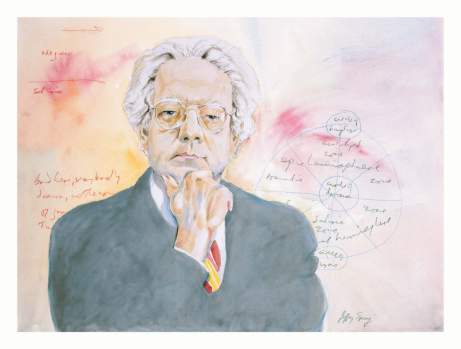

Said, as you may know, takes on Frye in his Humanism and Democratic Criticism and caricatures the Anatomy in the worst manner as the last bastion of what he calls “the humanistic system.” Frye is simply a whipping-boy, and from Said’s discussion there is little evidence that he actually ever read the Anatomy with any attention whatsoever. Ironically, his argument is the very opposite of what Frederic Jameson has to say about Frye in The Political Unconscious when he applauds his unique understanding of the literary imagination as the expression of a social vision. Instead, Said lumps Frye in with Arnold and Eliot as “disengaged humanists” who had no sense of the importance of history, social struggle or social class, or economic and political history. Frye, of course, knew volumes more about these things and their application to literary and cultural studies than Said, who is always, in the most gratuitous ways, showing off what he has read and knows (which is not as much as he pretends, as his absurd treatment of Frye makes clear). Far from ignoring the social and the historical Frye weaves them seamlessly, and in the most illuminating ways, into his insights and arguments about literature.

Here is a good example I read this morning. Now bear in mind that this–a brief paragraph among countless others of the same kind in his published writings and notebooks– was written by a critic who, according to Said, tried to insulate literature and culture from social reality and ran away from any discussion of history and class struggle:

In mimetic times there’s a social establishment in the middle of society, with an upper & lower class both dependent on it, parasitic to that extent, and hence, qua classes, essentially animal classes. The aristocracy acquires a powerful sexual smell from Romanticism once Lord Byron & the Marquis de Sade inherit the devil, along with the Gothic heroes. They get this partly from the fact that Eros has shifted from pastoral & garden metaphors to the numinous nature of forest and wilderness. The sexual symbolism of a lower class is less easily established, but there are traces of it in [Wyndham] Lewis’s Paleface images: Nazi sadism & the whipping of Jewesses in [Robert] Briffault’s Europa; the black man as a sexual symbol; the virile worker & the effete bourgeois (Lawrence’s gamekeeper); even Heathcliff). The beat & hippie people revive the childlike radical of aristocracy which makes it an Eros symbol, including the cavalier symbol hair. The “artist” too, of course, is an intermediate figure between aristocrat & beat, with the same satyrical display of balls.

This is what I would call serious cultural studies, of a quality and of a kind that Greenblatt and Said could never even dream of doing. Because they don’t know how to think about literature as a mythological, imaginative language; they are always reading at a descriptive level, or at an ironic level that is translated into a descriptive allegory. It is no accident that Said turns to Eric Auerbach and Mimesis as his model for how we should think about the relationship between literature and history. Ideological critics like Said are always thinking at a descriptive level, or at an ironic one that they immediately translate into a descriptive allegory. Frye’s rule-of-thumb, however, applies to the entire verbal universe, not a little corner of it: follow the archetype, and eventually it will give you everything you need: philosophy, history, society, race, class, gender (as the mantra goes), ideology (secondary concerns), and of course primary concerns all rolled into one.

And that’s the kind of reading I’ve got all the time in the world for. As the old song goes: H-h-h-how ya gonna keep ’em down on the farm after they’ve seen Paree?