The Educated Imagination was the first book by Frye I read, and it’s therefore always a touchstone for me. You never forget your first love. Meanwhile, Fearful Symmetry remains Frye’s most mind-blowing text, The Great Code his most challenging, and Words With Power his most expansive for practical critical purposes. But like many Frygians, I’m guessing, I regularly return to Anatomy of Criticism, and, it seems, almost involuntarily. Every once in awhile I find myself preoccupied by something from it that I seem to recall out of the blue. Thanks to an email exchange with Peter Yan and the cumulative effect of posts over the last week or so, I have been pondering an issue Frye briefly raises in Anatomy that gets relatively little attention (the exception perhaps being Bob Denham’s Northrop Frye and Critical Method): “demonic modulation.”

With demonic modulation Frye makes a much needed distinction between “the moral” and “the desirable”:

The moral and the desirable have many important and significant connections, but still morality, which comes to terms with experience and necessity, is one thing, and desire, which tries to escape from necessity, is quite another. Thus literature is as a rule less inflexible than morality, and it owes much of its status as a liberal art to that fact. The qualities that religion and morality call ribald, obscene, subversive, lewd and blasphemous have an essential place in literature but often they can achieve expression only through ingenious techniques of displacement. (AC 156)

How does demonic modulation manage this? By way of “the deliberate reversal of the customary moral associations of archetypes.” For example, in literature, whatever the current status of received moral standards,

a free and equal society may be symbolized by a band of robbers, pirates, or gypsies; or true love may be symbolized by the triumph of an adulterous liaison over marriage, as in most triangle comedy; by a homosexual passion (if it is true love that is celebrated in Virgil’s second eclogue) or an incestuous one, as in many Romantics. (AC 156-7)

A.C. Hamilton in Northrop Frye: Anatomy of his Criticism describes Anatomy, published in 1957, as very much a book of its time — so Frye’s reference to various forms of forbidden love as “modulations” must have been eyebrow-raising for many conventionally-minded readers. Frye does not call it that here, but what he is clearly talking about is literature’s unique ability to express primary concerns beyond the pervasive gravitational pull of secondary ones.

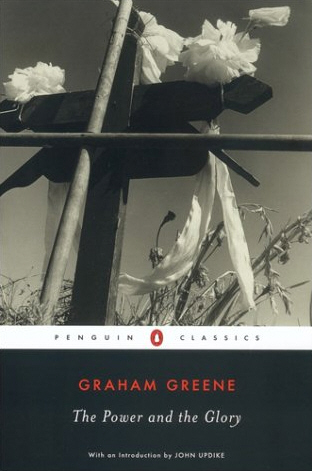

I’m pretty sure I can remember the first time I ever became aware of this in my own reading experience: Graham Green’s The Power and the Glory, which was an assigned text back when I was in the 11th grade. I remember struggling with the contradiction between Greene’s “whiskey priest”‘s all too human frailty and his compelling nature as a human being I felt I could love and identify with, despite his obvious failings. I’m also pretty sure that even though I wondered about it at the time, I was nevertheless grateful to accept that it was so. Literature was showing me something I otherwise couldn’t account for with any certainty; and within a year I read The Educated Imagination for the first time which articulated what I in some sense already knew but simply could not yet say.

Literature references ideology but does not promote it. Literature gives expression to primary concerns, most especially when they are contrary to the ideologies that readily suppress them. Desire may on occasion be moral, but the moral can never contain desire — and in the struggle between the moral as a secondary concern and desire as a primary one, desire always prevails. That, paraphrasing Wilde’s Lady Bracknell, is what fiction means.

I think the idea that primary concerns are more important than secondary concerns is itself a moral principle. I don’t like the idea of jettisoning the word “morality” just because the word is abused by ideologues. I would rather proceed by reclaiming and rehabilitating abused words. Morality just means good action. Are we also going to reject the word “good” or are we going to use it to mean what it actually means in quiet (or loud, if necessary) defiance of the murderers of language. Avoiding abused words leads to all kinds of conceptual contortions, and I believe it is one of the leading causes of stupidity. My attitude is that they are my words too, and I will use them to mean what they actually mean–I will fulfill their telos.

Morality is a word that represents a fact, the fact of some or every particular good act. To say that it represents a representation of a fact is the beginning of an infinite deferral of meaning. Words eventually have to mean something, and what they mean is reality, and reality is found not in representations but in direct experience of the particular. I realize I am getting over my head here philosophically, and I think I have a better way of explaining this which I hope to post soon.

Clayton, the reason that “primary concerns are more important than secondary concerns” is *not*, as you claim, “itself a moral principle” because it is *demonstrably* not so! Secondary concerns involve compelled belief and behavior enforced at the social level; primary concerns do not. Secondary concerns often involve little more than going along to get along; primary concerns involve choice — usually made alone and against a tremendous amount of inertial resistance represented by often crude and cruel social conventions. (Remember the days not so long ago when homosexuality was widely regarded as either “deviant” or simply a “lifestyle choice”?) It’s not that there shouldn’t be secondary concerns, but that they ought to be secondary, which they almost never are: hence Frye’s distinction. As he says in WP, we must allow primary concerns to become primary at this late stage in our civilized development, “or else.”

I appreciate your response Michael, but I think I need more explanation. I don’t understand how what you say is indeed the case and also demonstrably so. It was only last year that Rowan Williams called homosexuality a lifestyle choice, and he’s supposedly a liberal. Anyone who looks at Williams’s own justifications for his actions can see that they serve the needs of the power of the institution that he runs. In other words, they are not based on what is good or bad but on what is ideologically acceptable. The one thing you can say about ideology is that it is amoral, that its interests are orthogonal to morality. That ideology kidnaps the word morality in order to convince people that black is white and white is black does not make it an authority on morality. Morality is actual good and bad. Ideology is what people say is good and bad so that they can have power, power to do stuff that is not important or that is wrong.

You say that it’s not that there shouldn’t be secondary concerns. I’m reading Thoreau at the moment and of course he’s very good on this subject. He shows how we all give in more and more to the demands of secondary concerns simply because we cannot distinguish them from the primary ones. Of course there shouldn’t be secondary concerns, or at least we should be doing the hard work and making the hard choices that Frye sets for us and that Thoreau describes so well, of making the primary concerns truly primary.

The measure that Rowan Williams is indeed wrong is primary concern. Literature, unlike other verbal structures, places primary concern first — hence the possibility of “demonic modulation”: pirates, robbers, gypsies as representative of free and egalitarian societies; the love that dare not speak its name bolting out of the closet and speaking up! The only reason there is conflict on these issues is that we put secondary concern first and subordinate primary concern to it. In fact, the general subordination of literature to ideological considerations — which are thought to be more real, compelling, or (sigh) “relevant” (see Joe’s post on Target Knowledge) — is symptomatic of how far wrong literary criticism has gone since Frye.

Is the problem that we are identifying primary concern with desire? I may want to be a pirate, but that isn’t a primary concern, though it may indicate some primary concerns. Literature is wonderful in that it can give a form to desire, even those desires that are considered immoral, even those desires that actually are immoral. It does seem to me that desire and primary concern approach each other only through a process of clarifying desire, and that literature can perform a moral function by helping along that process.

The primary concerns/desires I am talking about are freedom of movement, sex/love, food, property. According to WP, they are associated respectively with the following “variations”: the Mountain, the Garden, the Cave, and the Furnace.

You may desire to be a pirate, but that’s not a primary concern. However, pirates may be rendered metaphorically (via the extra-moral principle of “demonic modulation”) to represent a free society, which *is* an expression of primary concern.

I’m writing on the fly on my busiest teaching day, Clayton, so I’m sorry for the brevity of my responses.

I think you’re right that literature performs a moral function by helping along the process of clarifying desires by way of primary concerns. If you (that is, anyone) thought that being a pirate were going to fulfill your primary concern for freedom, then it’s clear that you’ve got an awful lot to learn about pirates — and about the range of literary relations to them. As Wilde nicely observes, the realism of life detracts from it as a subject of art. He also said, of course, that there are no moral or immoral books; books are either well written or badly written. This is undeniably a man who deeply appreciated the aesthetics of morality — or, rather, how the moral may be approached through the apprehension of beauty. And, as Frye puts it in WP, the more spiritual that apprehension becomes, the more beauty will be understood to be the fulfillment of primary concern (for everyone, everywhere, without notable exception), and the more ugliness will be recognized as the denial of it. A starving child is not ugly. It is, rather, ugly that any child be allowed to starve anywhere, anytime, under any circumstances.

If that sounds self-evident, then consider this: the loony right in the US, led by the execrable Rush Limbaugh, is all over Obama for “responding too quickly” to the crisis in Haiti. The racism here of course is overt by this point. But it also follows that these are the kinds of people who are content that unspeakable suffering go on in places like Haiti as long as it advances the narrowest, least constructive imaginable political agenda. And it’s not like this is a rarity in everyday human life.

Ideology always seems to be hiding at its centre an angry and hungry volcano god demanding human sacrifice. Literature is our one sure stay against that.