“…a blend of the tragic, comic and satiric”

Lecture 17. February 10, 1948

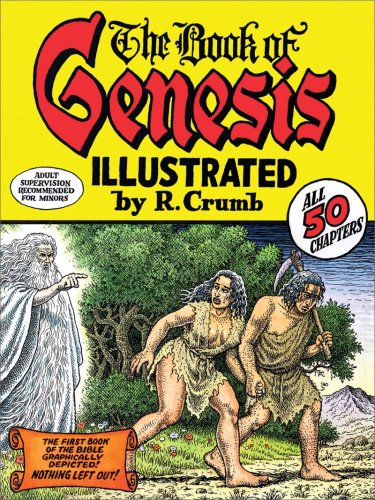

To understand Job, you must see that the book is a blend of tragic, comic and satiric. All great drama is a blend of these three. The satiric tone is a blend of the moral and the humorous. Pure humor is not satire; pure denunciation is not satire.

Satire is a detachment from evil; it brings out its wrongness and ridiculousness. You can’t find anything more detached from evil than God; therefore, there are some aspects of the sardonic in God, or the gods. This is inescapable in any serious religion. Wrath is the reaction of good when confronted with evil, and wrath is the opposite of irritation. God is incapable of irritation, which is a personal egocentric thing which desires to triumph over and score off someone. Wrath is impersonal, detached.

God speaks in the tones of the wrath of the sardonic. Yet these tones are different from Job’s friends who approach him with elaborate friendliness and politeness. They talk in vague, general terms about the goodness of good and the badness of evil.

Then their approach sharpens; the reproaches come clearer to a point of open antagonism. They are trying to hint that Job had better “‘get right” with God. They are trying to interpret their own sense of the wrath of God, of man in an evil state. But Job insists that he’s done nothing wrong. The friends become irritated; they want to score him off. Job tries to score them off, too. All agree there must be some justice somewhere. Only Job’s wife suggests something else: curse God and die. At the end, God curiously enough seems of the same opinion. Man searches for a God equal to him. God feels the same way; he wants a man equal to him.

The dialogue breaks down into a deadlock. If Job has done nothing wrong, then nothing makes sense. His friends are pious Jews thinking in terms of the Hebrew law, the best of the Pharisaic mind that Jesus condemns. They try to interpret God’s design in terms of the law. Job comes to the discovery that rain falls on the just and unjust alike; the sun shines upon evil and good alike.

Job, his three friends, and Elihu are all under the same cloud. The breakdown point is that there is no revelation of God to Man. All seems to be mystery. The collapse is tragedy and satire, not comedy.

Tragedy and satire are inseparable. There is an ironic kernel in all Shakespeare tragedies. Hamlet’s death is a tragedy, yet it takes place after a muddled attempt at revenge. Horatio must tell that Hamlet has been a damn fool. In Othello’s last speech he is trying to cheer himself up and rescue some fragment of dignity. It is not that he realized what a fool he has been, but what a fool he is. In Antony and Cleopatra, the Antony who held the stage in Julius Caesar, the demagogue, in this play is crowded right off the stage by Cleo. She has him killed off in Act IV and has the fifth act to herself. She puts on a good show, but the irony is that it is a good show. Octavius comes in at the end of her show and says, “Oh yes, I heard she was doing some research on a painless way to die.” The hanging of Cordelia, in Lear, blasts any theory that there is a moral order in tragedy.

The point of tragedy is not punishment, but that the hero fell, whether he deserved it or not. That is the irony.

The author of the Book of Job is not trying to clear God’s name, as Milton was. There is no self-defensive, aggressive tone as in Milton’s God. At the end, God speaks with what seems colossal impudence. He feels he has a right to condemn Job, in a sense, for feeling that he is righteous in his own eyes. The reader has the curious feeling that God has done something wrong, in view of the prologue.

Continue reading →