You may register with the upcoming Frye Festival in Moncton, New Brunswick here.

Monthly Archives: February 2010

More Frye and the Bible

Blake’s Plato

Reponding to Nicholas Graham’s post

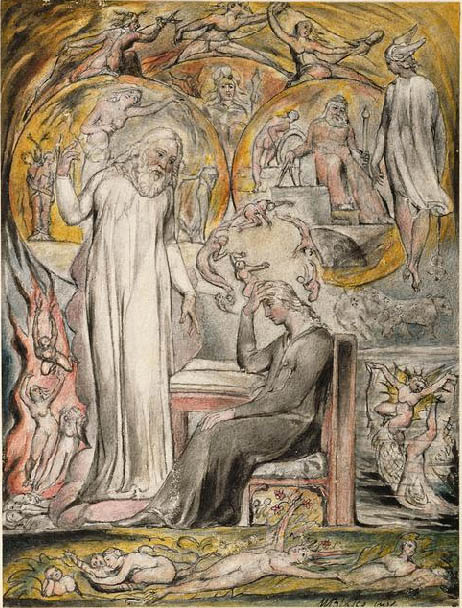

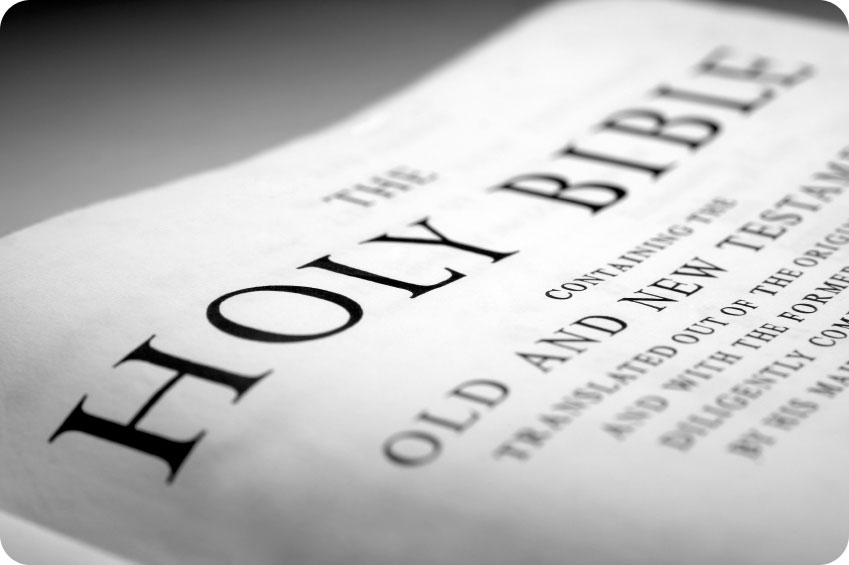

I certainly agree that Frye’s reading of the Bible is guided by typology and that there is a certain prophetic power in his biblical criticism. I was by no means trying to give a full account of Frye’s reading of the Bible. My remarks were in the context of the earlier posts about the meaning of the phrase “literary criticism of the Bible.” All I was trying to suggest was that Frye’s approach relies on two fundamental literary principles, myth and metaphor or narrative and image––the mythos and dianoia that Frye devoted so much space to in Anatomy of Criticism. Typology and prophecy, as I understand those terms, are terms from biblical, rather than literary, criticism. I agree also that “vision” is also absolutely central to Frye’s enterprise, and I wrote a fairly long chapter in my book on Frye and religion (89–125) trying to make a case for its centrality and relating it to terms such as “insight,” “enlightenment,” “epiphany,” “recognition” and (the central visionary faculty) “the imagination.” But again “vision” is a term that does not spring from the vocabulary of literary criticism, though it is perhaps obliquely connected to Aristotle’s opsis. No one would want to reduce Frye’s reading of the Bible to myth and metaphor. But they are literary principles, and so no one would want to ignore them either. As I understand Frye, “vision” and “prophecy” belong to what I called the Bible’s centrifugal, kerygmatic thrust.

Nicholas Graham: Frye and the Bible

Giovanni di Paulo, Dante and Beatrice Leaving Heaven, ca. 1465

Responding to Bob Denham’s post

I like and agree with all that you say about Frye and the Bible, Bob, but feel there are a few things missing, like typology and prophecy. To say that Frye is looking at the Bible from the point of view of a literary critic is correct but seems to me to be a far too cold and detached statement–Frye as a scientific anatomist.

In Fearful Symmetry Frye is learning from Blake and teaching us that the Bible is a complete book of vision. With my philosophical and theological frinds I have enjoyed many heated and lively conversations, but we always seem to reach an impass when we come to the word “vision”. Their favorite word is “insight”, the eureka moment, and this seems to be pretty well an established occurrence in consciousness, and the title of a major work by that other great Canadian thinker, Bernard Lonergan. This “insight” is the basis for an alternative to faculty psychology, dealing with the soul and its attributes, which has now been abandoned in the wake of scholasticism. The nearest scholasticism comes to Blake’s “vision” is with the word “emanation”, as in Aquinas’ “intelligible emanations”, our participation through the act of “insight” in the light or mind of God. Understanding is what we achieve each time we have an “insight”. The historian Herbert Butterfield states that the rise of modern science outshines everything since the birth of Christianity. Modern science comes with the Enlightment and philosophers like Paul Ricoeur, Gadamer, Eric Voegelin and Leo Strauss are now trying to dismantle its stranglehold and go beyond it.

In this sense, Frye does not approach the Bible as a scientist or literary critic but, instead, as a prophet and poet. What emerges from Fearful Symmetry is Blake’s universal cry that we find at the opening of his poem Milton: “Would to God that all the Lord’s people were Prophets.” Numbers XI. ch. 29 v.

To go beyond either/or, Frye approaches the Bible both as a literary critic where he suspends value judgements but also as a prophet like Jeremiah where he uses value judgments to tear down and to build up. [See Jean O’Grady’s brilliant article “Re-valuing Value“.] The key to prophecy is typology, the Medieval approach to the Bible, displayed to us splendidly in Dante’s Divine Comedy. In “Paradiso” Canto 6, Justinian is the only speaker, and here we deal with the Law; canto 10, the Circle of the Sun, the Circle of the Sages, we deal with Wisdom; canto 17 deals with Prophecy. His great, great grandfather tells Dante must go back to earth and assume the mantle of the prophet and poet. Armed with the phases of revelation: Law, Wisdom, Prophecy, Etc., Dant must construct for us The Divine Comedy, which is nothing less than a recreation of the Bible.

Frye’s engagement with the Bible brought about a fundamental change in him as it did in Dante, and it was this change into prophet and poet that was necessary before he could present us with his lasting emanation, The Collected Works of Northrop Frye, which we must learn to read as the Bible for our time.

Quote of the Day

Frye and the Bible

Responding to comments by Russell Perkin and Michael Happy

It seems to me that Frye is looking at the Bible from the point of view of a literary critic. He begins with the assumption that, unlike other sacred books, the Bible is a unity. He is interested in the pursuing this unity as it manifests itself in the Bible’s myths and metaphors. The former he examines in terms of the movement from Creation to Apocalypse, with all of the lesser up and down U–shapes in between. The latter he examines largely in terms of recurring images. He of course brackets out any number of other features that a literary critic might legitimately want to investigate, especially those having to do with literary texture. His concern is with structure. That’s the centripetal thrust of The Great Code, Words with Power, and his Bible lectures. According to the class notes from his Religious Knowledge course, he called this the synthetic approach. The centrifugal thrust, largely absent from his Bible lectures, has to do with the kerygmatic myths to live by. That is, as a sacred book, the Bible is more than literary. Frye worries a great deal about what to call this, finally settling on “kerygma.”

One can approach a written text, sacred or otherwise, from any number of perspectives––biographical, historical, formal, sociological, cultural, religious, and so on. When I was in school in the 1960s biblical scholars such as Gerhard von Rad and Martin Noth were engaged in a type of interpretation called redaction criticism, which began to pay attention to large units of the Bible, such as the first six books, as creative, literary forms in their own right. Since that time there has been an explosion of literary approaches to the Bible, and there is a large industry today devoted to the poetics of biblical narrative and imagery. The degree of interest among Biblical scholars in such approaches is revealed by a glance at the annual programs of the American Academy of Religion and the Society for Biblical Literature. The dialogue works both ways: we have literary critics interested in the narrative and metaphorical features of the Bible, and we have biblical critics interested in the Bible’s literary features. Not long ago I was glancing at study of that most intractable book, the Book of Revelation, by Leonard Thompson, a well known biblical scholar. Thompson realizes that he can’t crack the code of Revelation without speaking about its genre, its narrative structure, and its metaphoric unity, all of which are literary matters. Which is pretty close to Frye’s approach.

One of my favorite examples of Frye’s mythical–metaphorical approach is his commentary on the Priestly and Jahwist creation accounts in chapters 5 and 6 of Words with Power. Whether the correct label for this “a literary criticism of the Bible,” I dunno. I guess I’d say it’s a reading of the Bible from the perspective of a literary critic who is interested in texts as wholes and in the structure of their narratives and imagery. Or is all of this too obvious to need remarking?

I suppose one doesn’t have to be a literary critic to pay attention to features of a text that are literary, but if you’re trained to consider the centrality of such things as metaphor in any text, you’re more likely to see things that those untrained do not. Spend ten minutes, for example, leafing through any collection of hymns. You’ll discover that God is a mighty fortress, Christ is a master workman, Christ is a star of the East, Christ is a dying lamb, the earth is a story teller, the Holy Spirit is a dove or a divine fire or a wind, Christ is a solid rock and similar figures from the mineral world (such as Rock of Ages), God’s mercy is a bright beam, Christians are soldiers (and also from that hymn, we are the body of Christ), the hour of prayer is sweet, the heart is a dwelling place, Christ is the light of light, Jesus is a shepherd; and of course all the royal metaphors imported from the Old Testament of the “Christ is king” or “Christ is ruler” variety and the associated metaphors of crowns, diadems, and thrones. Some hymns give us rather difficult instructions, such as “fold to thy heart thy brother” or “lift up your hearts,” the folding of a brother and the lifting of a heart seeming to be rather difficult things to do literally. Sometimes we get dual metaphors, as in the hymn “O Holy City,” where we’re told that “Christ the Lamb doth reign,” a figure that combines a pastoral and sacrificial image with a royal or regal one: Christ is a lamb: the lamb is a king. In “O Master of the Waking World,” we’re told that Christ has all the nations in his heart, an extraordinary metaphor that rather strains our powers of comprehension. In another hymn we’re called on to deliver our land from “error’s chain.” Why “chain”? Well, the hymnist needs a word to rhyme with “plain” and “slain,” but we nevertheless sense the direction in which the figure takes us: the heathen nations (the hymnist mentions India and Africa, along with, of all places, Greenland) are imprisoned (that is, chained) by error. Even in “My Country, ’tis of Thee” freedom is said to be a holy light, and as one of the imperatives is for it to ring from the mountain side, freedom also seems to be a bell. In “It Singeth Low in Every Heart” we’re told that the dead “throng the silence of our breasts,” indicating that in our breasts, where everything is silent, we have a host of dead souls or maybe just dead people hanging out, an image that is something of a problem for the literal minded. In “Praise to the Lord, the Almighty,” we were told in the first stanza that “God is health” and in the second stanza that God is a bird. As we’re sheltered under the wings of God, this appears to be a mother bird, a hen perhaps. The hymnist doesn’t say that God is like a mother hen, but that he is one. In one of the choral responses we implore the Lord to makes us a sanctuary, which means a sacred place or a place of refuge.

My guess is that form critics and redaction critics and canonical critics and reader–response critics are less likely to be attuned to such metaphors than a critic interested in figurative language.

Saturday Night Bach

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wyOf_L4cNHc

Glenn Gould, Piano Concerto No. 7 in G Minor

Quote of the Day

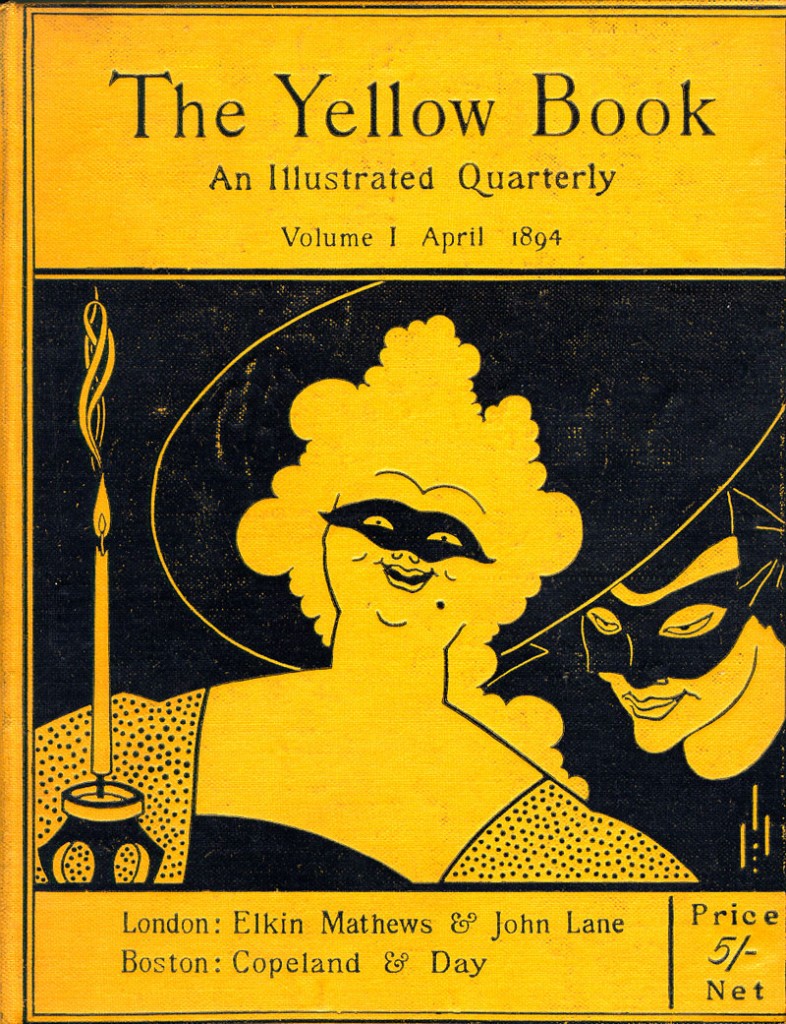

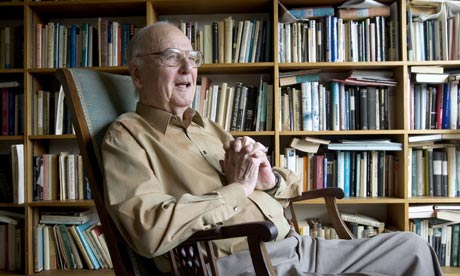

“There was a period, when I was a young lecturer, when there were literary critics with immense reputations. I’m thinking of people like Northrop Frye, for example, who ruled the world with Anatomy of Criticism. It’s never cited or quoted anywhere now.”

Sir Frank Kermode, Interview with John Derbyshire, New Statesman, 5 February 2010

TGIF: Newswipe

More from the great Charlie Brooker: “Nobody knows anything.”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dm4GiyyVKQQ

Criticism in Society

Imre Salusinszky in his new role as columnist for The Australian

Imre Salusinszky’s Criticism in Society stands above all other similar collections of interviews with contemporary critics. Here is a footnote to Russell’s post, adapted from something I wrote in the introduction to the Collected Works Anatomy.

In Imre Salusinszky’s Criticism in Society, an exemplary collection of interviews with Frye, Derrida, and seven others in the pantheon of the literary establishment (Harold Bloom, Geoffrey Hartman, Frank Kermode, Edward Said, Barbara Johnson, Frank Lentricchia, and J. Hillis Miller), it is clear that Frye remained an informing critical presence in the late 1980s in the consciousness of most of these critics. (Outside of Derrida, Barbara Johnson is the only interviewee who does not refer to Frye.) The interviews begin with Derrida and Frye, and those that follow often play off against the two grand masters. Each critic read the previous interviews and thus had the opportunity to comment on what had come before. [Note that most of these interviews can be read at the above link to the text.] This, along with the comments each critic (save Derrida) is asked to give about Wallace Stevens’s “Not Ideas about the Thing but the Thing Itself,” gives a coherence to the collection. [An animated video of Steven’s reading the poem is included after the jump.] The first interviewee, following the conversations with Derrida and Frye, is Harold Bloom, whose influence of Frye is substantial and longstanding.

Harold Bloom read Fearful Symmetry shortly after it was published, and he reports that it “ravished my heart away. I thought it was the best book I’d ever read about anything. I must have read it a hundred times between 1947 and 1950, probably intuitively memorized it, and will never escape the effect of it.” Bloom adds that he “wouldn’t want to go read it now because I’m sure I would disagree with all of it “Criticism in Society 62). In his foreword to the Anatomy, Bloom remarks that Frye’s view of poetic influence was, as mentioned earlier, a matter of “temperament and circumstances.” This is a reference to correspondence the two had in 1969 about Bloom’s theory of “the anxiety of influence.” Bloom had written Frye: “I can understand why you do not see Poetic Influence as an anxiety or melancholy, as I do, because of what you call the myth of concern” (letter of 18 January 1969). Frye replied: “If you mean influence in the more literal sense of transmission of thought and imagery and the like from earlier poet to later one, I should think that was simply something that happens, and might be a source either of anxiety or of release from it, depending on circumstances and temperament. But of course it is true that the great poet’s maturity brings with it a growing sense of isolation, of the kind one feels in Yeats’ Last Poems, Stevens’ The Rock, and perhaps even Blake’s Job series” (letter of 23 January 1969). Bloom then replied, “I don’t, as you say, mean influence in any literal sense, since I agree that it simply happens, and temperament alone governs whether it causes anxiety or not. I think that I am studying what your other remark indicates, the deepening isolation of the strong poet’s maturity, particularly as one feels it in the later stages, in Paradise Regained & Samson, in Wordsworth from 1805 on, in Jerusalem, as well as in late Stevens and Yeats” (letter of 27 January 1969). These remarks suggest that Frye did not at all reject Bloom’s theory of the anxiety of influence because influence was a matter of “circumstances and temperament”: they agree that anxiety has something to do with the mature poet’s isolation. Bloom is, therefore, very selective in his Foreword to the Anatomy about what Frye had conveyed to him in their correspondence.

In A Map of Misreading Bloom remarks that Frye’s myths of freedom and concern are a Low Church version of Eliot’s Anglo-Catholic myth of Tradition and the Individual Talent, but that such an understanding of the relation of the individual to tradition is a fiction. “The fiction,” Bloom says, “is a noble idealization, and as a lie against time will go the way of every noble idealization. Such positive thinking served many purposes during the sixties, when continuities, of any kind, badly required to be summoned, even if they did not come to our call. Wherever we are bound, our dialectical development now seems invested in the interplay of repetition and discontinuity, and needs a very different sense of what our stance is in regard to literary tradition” (A Map of Misreading 30). This remark contains more than a hint of the anxiety of influence. But regardless of whether one agrees with Bloom’s projection about what our development “seems” to involve, it is mistaken to suggest that Frye has failed to observe the “interplay between repetition and discontinuity.” In words that could stand as a motto for theories of misprision, he says that “the recreating of the literary tradition often has to proceed . . . through a process of absorption followed by misunderstanding” (The Secular Scripture 163). Even if Frye’s ultimate allegiances are to a continuous intellectual and imaginative universe, to order rather than chaos, to romance rather than irony, he cannot be accused of having turned his back upon the discontinuities in either literature or life. Nor should we let Bloom’s remark deceive us into thinking that in the 1960s Frye began suddenly to summon continuities as a bulwark against the changing social order. The central principles in Frye’s universe remained constant over the years.

The history of Bloom’s relationship to Frye is one of attraction and repulsion. Bloom can say, on the one hand

To compare lesser things with greater, my relation to Frye’s criticism is Pater’s relation to Ruskin’s criticism, or Shelley’s relation to Wordsworth’s poetry: the authentic precursor, no matter how one tries to veil it or conceal it both from oneself and from others. Frye is surely the major critic in the English language. Now that I am mature, and willing to face my indebtedness, Northrop Frye does seem to me . . . a kind of Miltonic figure. He is certainly the largest and most crucial literary critic in the English language since the divine Walter [Pater] and the divine Oscar [Wilde]: he really is that good. I have tried to find an alternative father in Mr Burke, who is a charming fellow, but I don’t come from Burke: I come out of Frye. (Criticism in Society 62)

On the other hand, Bloom never abandoned his quarrel with his critical father. In the Salusinszky interview, he reaffirms the statement he made about Frye’s “myth of concern” being a Low Church version of Eliot, though he says he would “phrase it a little more genteelly now, out of respect for Mr. Frye” (ibid., 63). Moreover, Frye was never agonistic enough for Bloom (“Frye may be the first great critic in English literature whose pugnacity is diverted to other purposes”), and Frye’s view of the common reader and of democratizing the critical process always grated against Bloom’s elitist sensibility:

Mr Frye has, thank heavens, nothing in common with the Marxists, pseudo-Marxists, neo-Marxists, und so weiter, but like them he has idealized the whole question of what might be called––to use his own trope for it––the extension of the franchise in the realm of literature and literary study. Idealization is very moving: it is also very false. It allows profound self-deceptions, at both the individual and the societal level. Literature does not make us better, it does not make us worse; the study of it does not make us better, it does not make us worse. It only confirms what we are already, and it cannot authentically touch us at all unless we begin by being very greatly gifted. (ibid., 58)

Criticism and Society

While looking for a quotation in David Lodge’s 1990 book After Bakhtin, I rediscovered his review of Imre Salusinszky’s Criticism in Society, which is reprinted as the last essay in After Bakhtin. Criticism and Society is a collection of interviews with Northrop Frye, Jacques Derrida, and a group of influential critics at American universities, recorded by Salusinszky in the mid-1980s, at the moment when deconstruction was beginning to give way to schools of criticism more concerned with ideology and social identity. Some readers of this blog will know Imre Salusinszky’s work on Frye; he left academe some time ago to work for the newspaper The Australian and is now a well-known political and cultural commentator in Australia.

Criticism in Society came out the year that I defended my PhD, and I remember that it was read avidly by everyone with an interest in literary theory. I’m sure most readers were like myself in not fully taking in the prominent position that Frye was given in the book: we were mostly too interested in what the stars of Yale, Columbia, and Duke had to say. Lodge sums up Salusinszky’s premise in his own words as follows: “since literary criticism was virtually monopolized by the universities, it has become of all-absorbing interest to its practitioners and a matter of indifference or incomprehension to society at large.”

Lodge’s review is particularly resonant at the moment, as the humanities in the university seem to be returning to the same austerity conditions that prevailed during the 1980s. He observes that among the critics interviewed, “only Frye and Derrida . . . mention the problem of obtaining public funds for the humanities. If Mr Salusinszky had interviewed a batch of British academic critics at the same time he would have heard about little else.”

Lodge quotes Frank Lentricchia defending socially engaged criticism from an attack by Harold Bloom, then observes:

But there is a certain factitiousness about the counter-attack, betrayed by the familiar ‘Harold’. Nearly all the interviewers refer to each other, even when expressing strong disagreement, by first names – Harold, Geoffrey, Jacques, etc. (though not ‘Northrop’ – in this as in other respects, Frye is the odd man out. I wonder if anyone dares to call him Northrop). This style of naming again reminds one of the world of sport, where top athletes who compete fiercely against each other on the football field or tennis court share a kind of professional camaraderie at other times, a mutual respect based on their sense of belonging to a professional élite.

I wonder, however, whether criticism or theory has such an absorbing interest even for aspiring practitioners today? Are there nine critics today whose words in interview would be eagerly perused – and if not, is that a good or a bad thing? Has the pendulum swung back to interest in the creative writer? Perhaps we would rather read interviews with – to pick a few names randomly – Zadie Smith, Salman Rushdie, Nino Ricci, Martin Amis, or Lorrie Moore.