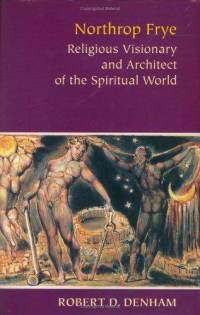

Bob Denham’s “Northrop Frye’s ‘Kook Books’ and the Esoteric Tradition,” mentioned earlier in a recent discussion here, is now available in his new book published in our library. The essay was originally published in Frye and the Word, and appears in an expanded version in Bob’s Northrop Frye: Religious Visionary and Architect of the Spiritual World. It makes for very stimulating reading. It is, among other things, a powerful demonstration of what it means to have a genuinely open mind. Frye had one, and so does Bob, who takes seriously Frye’s interest in a host of books, most of which no self-respecting critic would normally be caught dead with. The material covers an astonishing variety of subjects usually regarded as lacking any scientific or scholarly credibility – the kinds of things you’d expect to see in occult or New Age bookshops. It is almost unbelievable the number of these volumes Frye went through and annotated. Bob’s essay offers an exhaustive catalogue of Frye’s reading in this area – a list that is itself over nine pages long – and painstakingly clarifies the source and nature of Frye’s critical interest in such apparently bizarre and arcane texts. As Bob shows, Frye was not just a liberal thinker, he was an utterly free thinker in view of what he refused to dismiss as unworthy of attention simply on the basis of restrictive scholarly norms. He was compelled solely by the degree to which any of these works offered a door of perception into the mythological, imaginative, and spiritual universe. Frye, it is clear, had pretty well permanently removed the mind-forged manacles most of us wear most of the time. This is a very lively essay, and I wish we had a YouTube version of Bob reading it with that wonderful smile and warm Southern drawl of his, as he did at the Frye and the Word conference a decade ago.

I have read the essay before, including its earlier versions, but this time it resonated in a completely new way with my ongoing reading of Poe, who has been much on my mind after three weeks of engagement with him in my American literature course. Bob very acutely draws the distinction between Frye’s negative view of religious Gnosticism and its rejection of the creator and the material world as inherently evil, and his sympathetic attitude to those gnostic poets who viewed the imagination as a means of spiritual transcendence. The latter are “bees of the invisible,” as Rilke called them: masters of metaphor, visionaries in service of the anagogic and kerygmatic, they transform the pollen of the visible into the golden honey of the invisible world of spiritual reality. As Bob points out, the exemplary poets for Frye in this regard were Mallarmé, most notably, and Rilke. He may also have had in mind Poe, whose literary genius he held in high regard. Poe of course was a revered figure for Mallarmé and the Symbolists, the first to “purify the language of the tribe,” and Rilke is clearly a descendent of the same movement. Many knowledgeable readers of Poe have never really come to terms with this critical judgment, underestimating Poet’s artistry and attributing his exalted reputation in Europe to the creative misprisions that occur when translating from one language and culture to another. Fortunately, there are exceptions to the obtuseness with which American and English critics have treated Poe. The most splendid instance is the American poet and translator Richard Wilbur, whose take on Poe, though not devoid of moral reservations, is unmatched for its ability to read on an esoteric and allegorical level – that is, archetypally. Wilbur never cites Frye, and I don’t know if he was at all informed as a critic by his work, but his approach to Poe as a brilliant symbolic writer is reminiscent of Frye’s in many respects. They would have benefited greatly from reading one another.

In the Anatomy Frye calls Poe an uninhibited and “more radical abstractionist than Hawthorne” (139). Another way of putting it is that Hawthorne resisted his own “kookiness” and consequently his social and moral anxieties were at odds with his archetypal genius. Poe had no such anxieties. It was the clarity and lucidity of Poe’s cosmological vision, his unapologetic gnosticism and his trust in the power of imagery, that made him a great symbolic writer, one whose poetic vision is perhaps most fully realized not in his lyric poetry but in his tales. His writings always reveal both an exoteric and an esoteric level. There is no question about Poe’s exoteric appeal; he is an extremely popular writer even today. At the esoteric level, the level that appealed to the Symbolists, and to Wilde and Borges, the tales are all, in one way or another, about the destiny and struggle of the soul to escape the fetters of space and time and achieve transcendence in the invisible world. As did Blake, Mallarmé, and Rilke, Poe viewed art and literature as the Great Code, another Way – another way than religion – to achieve that transcendence.

Even the mystifications and hoaxing in Poe’s writings appear to be part of the hermetic tradition, as is the smearing of his reputation by accusations of charlatanism and immoral behaviour. Bob points out that Frye’s final judgment on Helena Blavatsky was a positive one, and that he ascribes her reputation as a confidence woman to the inevitable adversity of someone communicating an oracular wisdom that is out of the ordinary and difficult to make public without meeting scepticism and hostility. This is doubtless why, as Bob reminds us more than once, any references to the hermetic tradition, and all the more so to the “kooks,” Frye mostly confined to his notebooks. Be gentle as the dove, and wise as the serpent. It may have been a whiff of this interest in the occult on Frye’s part that Marshall McLuhan recruited as one piece of evidence in his paranoid fantasy that Frye was a Freemason. As Bob’s essay makes clear, there is no question about Frye’s interest in the occult and the paranormal. Frye made use of everything he could lay his hands on, but very little of what he used was a matter of belief.

I also had a chance to read another essay in Bob’s book, “Common Cause,” which offers a very perspicuous overview of Frye’s ideas on education. The common cause here is not the society that exists but the society we have failed to create. It is an exhilarating read, especially these days when so much that is most essential to education, at every level, is being swept aside in the name of technological advancement and the requirements of corporate capitalism. The primary role of education, in Frye’s view, had only one final cause, in the Aristotelian sense. The purpose of education is the creation of a society informed by a genuine social vision. Bob brings this visionary conception of education very much to the fore of Frye’s thought.

One of my favourite moments is a passage by Frye Bob quotes near the close. More and more we are hearing terms like self-directed or inquiry-based learning celebrated as the new and better way to provide for the instruction of our students, more “relevant” – a word Frye excoriated – more aligned to the alleged contemporary economic necessity of “life-long learning.” Necessity is always the apology of ideology. As Frye puts it: “An ideology normally conveys something of this kind: ‘Your social order is not always the way you would have it, but it is the best you can hope for at present, as well as the one the gods have decreed for you: Obey and work’” (WP 24). What these buzz words really come down to is an abdication of the teacher’s responsibility in the classroom, the result, of course, of the hapless response of educational administrations to the expediency of empty pockets and the consequent mushrooming of class sizes beyond any reasonable scale. What is self-directed education if not the demand that students take over their own education, in the absence of a structured classroom and a teacher they can engage with as someone with authority who is genuinely engaged and concerned with them and the subject matter? Imagine a tennis instructor throwing someone a tennis racket and ball, and saying I’ll be back in an hour when the lesson is over and you can tell me how your game is coming along. Bob quotes the following passage from Frye:

[E]verything connected with the university, with education, and with knowledge must be structured and continuous. Until this is grasped, there can be no question of “learning to think for oneself.” In education one cannot think at random. However imaginative we may be, and however hard we try to remove our censors and inhibitions, thinking is an acquired habit founded on practice. . . . We do not start to think about a subject: we enter into a body of thought and try to add to it. It is only out of a long discipline in continuous and structured thinking, whether in the university, in a profession, or in the experience of life, that any genuine wisdom can emerge. (Education, 376–7)

This is all by way of a strong recommendation to take a look at Bob’s wonderful collection of essays. There is no one reading Frye who can do what he does, and with such infallibility and graceful ease.