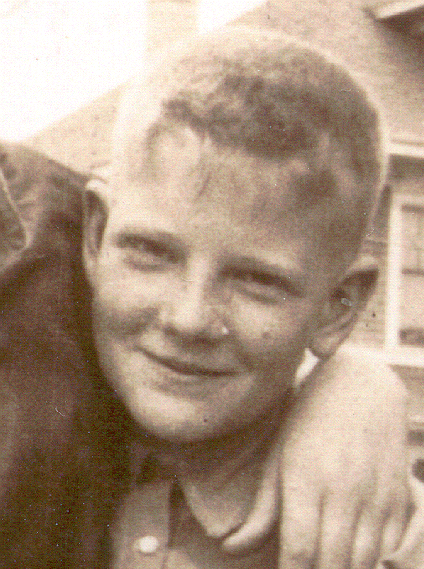

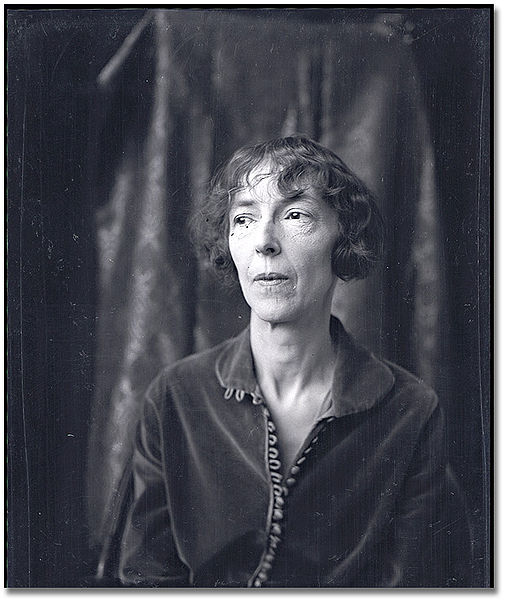

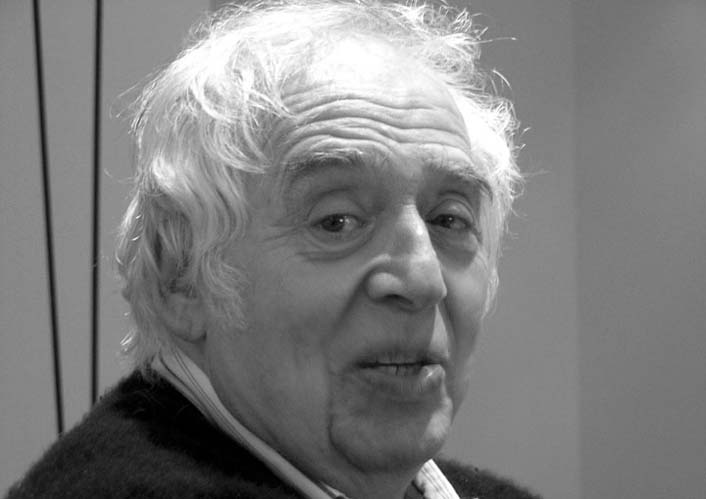

Frye and Helen: the expression on his face is sweetly suggestive of his impassioned letters to her during the 1930s

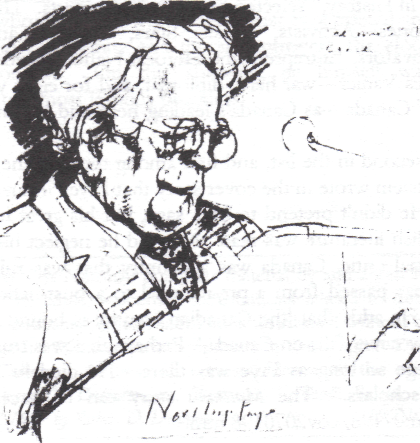

Today is Frye’s birthday (1912-1991) and an opportune moment to hear what Frye has to say about himself.

His intermittent diaries between 1942 and 1955 contain just two birthday entries.

From his 1942 diary:

Thirty today. Many good resolutions, most broken already. (CW 8, 6)

From his 1950 diary while staying at Harvard and writing his seminal “Archetypes of Literature“:

Today was my thirty-eighth birthday. Helen & I went down to the Harvard Co-operative Store (they call & pronounce it the “Harvard Coop”) & got me a summer suit & a lot of miscellaneous things, socks & tie & so on . . . On the way back I stopped at a liquor store & asked if if there were any formalities about purchasing liquor. He said the formality consisted only in the possession of cash…

It’s important for me to get along on a concentrated job as soon as possible, because travel, which is said to broaden the mind, only flattens mine. The exposure of my naturally introverted mind to a whole lot of new impressions confuses me, because I’m more at home with ideas, I’m not naturally observant, and what impressions I do get are random & badly selected. Also they’re compared with the more familiar environment back home and, as I don’t know the new environment, the comparison is all out of focus. (ibid., 406)

We get much more of this sort of autobiographical detail in his letters, written between the ages of 19 and 24, to Helen Kemp.

Postmarked 14 June 1932:

The Muse is still stubborn. I have a good idea but no technique. I have a conception for a really good poem, I am pretty sure, but what I put down is as flat and dry as the the Great Sahara. I guess I’m essentially prosaic. I can work myself up into a state of maudlin sentimentality, put down about ten lines of the most villainous doggerel imaginable, and then kick myself and tear the filthy thing up. However, I got out the book of twentieth-century American poetry from the library and that cheered me up. There are bigger fools in the world. (CW 1, 19-20)

Postmarked 25 August 1932:

What I am worried about is my own personal cowardice. I am easily disheartened by failure, badly upset by slights, retiring and sensitive — a sissy, in short. Sissies are very harmless and usually agreeable people, but they are not leaders or fighters. I would make a very graceful shadow boxer, but little more. I haven’t the grit to look the Wedding Guest in the eye. “Put on the armor of God,” said a minister unctuously to me when I told him this. Good advice, but without wishing to seem flippant, I don’t want armour, divine or otherwise — snails and mud-turtles are encased in armour — what I want is a thick skin. (ibid., 63)

11 October 1933:

You say I am necessary to your existence. Does that mean:

a) That I am 135 pounds of mashed turnip; something necessary in the way of companionship — somebody to tell one’s troubles to — somebody who will pet you and spoil you and cuddle up to you when things go wrong?

b) That I am a condiment, bringing a sharp tang and new zest to existence, reminding you of the world, the flesh and the devil, and so humanizing you?

c) That I am a stimulant, helping to correlate your activities, encouraging your talents and spanking you for your weaknesses?

d) Or, that I am a narcotic, a drug, very powerful, to be taken, as you say, in small doses, temporarily relieving you, like a headache powder, from your ethereal worries by plunging you into an orgy of physical excitement which leaves you exhausted and silenced?

e) Or that I am an insufferable bore who stays too late?

f) Or a combination of the above?

You see, being a man, I’m so densely stupid. I haven’t any sort of intuitive tact. I am your typical male — whenever you get depressed I don’t know anything except what I personally want to do — that is, take you in my arms and strike solicitous and protective attitudes. If there’s any crying to be done, I want it done on my shoulder. I want to be present and look helpful whenever you are in difficulties. (ibid., 90)

Continue reading →