Responding a little more to Russell Perkin’s last post:

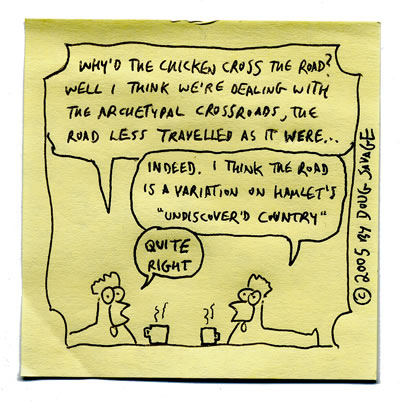

Your “superstitious” response to teaching Oedipus Rex is understandable. I recall a workshop, where a teacher (after 30 years experience) didn’t feel ready to tackle Oedipus Rex, which struck me as odd, seeing that the plot seems pretty reader friendly, as opposed to “writerly,” to use Roland Barthes’s term. But now I know how deep the play is after applying Frye to it.

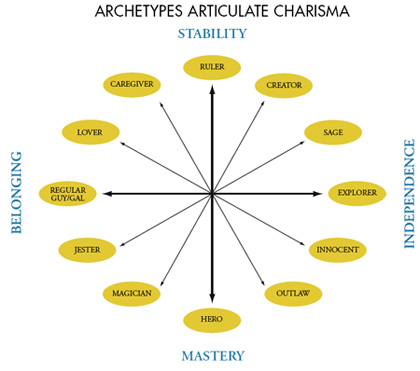

Frye’s archetypal criticism effectively places the work at the centre of the literary and social universe, where the Bible, Literature, Film, Popular Culture, Literary Criticism, Psychology, and Sociology orbit around it.

Bible:

Reuben sleeps with Israel’s concubine (Genesis 35:22).

Adam rejects the Sky Father to be with the Earth Mother.

Jesus is the opposite of Oedipus: Oedipus kills Father and possesses mother sexually. Jesus obeys Father (Father kills son) and marries mother spiritually, as He is everyone’s (The Church’s) bridegroom.

The curse and plagues and unknown suffering echoes Moses and the Pharoahs and Job.

Literature:

Countless stories of Father killing son, son killing father, incest, search for origins, prophecy: see “My Oedipus Complex” by Frank O’Connor.

Film:

Too many to count, but most popular include Killing of the Father (James Bond: The World is Not Enough, Die Another Day; Gladiator, Star Wars).

Popular Culture:

The Rap song by Immortal Technique Dance with the Devil where gang initiation results in son raping and killing mother.

Literary Criticism:

The Oedipus myth is used as a critical term/conceptual myth by Harold Bloom, in ways the writer writes (anxiety of influence) and readers read (misreading), both trying to kill off earlier influence.

Psychology:

Obviously, The Oedipus Complex. Even the 5 Stages of Grief (Oedipus goes through Shock, Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Acceptance) appear here first. And Jung’s idea of synchronicity, or meaningful coincidence, is the basis of every literary action/plot.

Sociology:

The search for the adopted parents, usually the father, is a major issue given the popularity and technology of sperm donors.

Video of Immortal Technique’s Dance with the Devil after the break.

Continue reading →