Courtesy of Clayton Chrusch:

“The release of creative genius is the only social problem that matters.” Fearful Symmetry

See the full paragraph in Clayton’s comment here.

Courtesy of Clayton Chrusch:

“The release of creative genius is the only social problem that matters.” Fearful Symmetry

See the full paragraph in Clayton’s comment here.

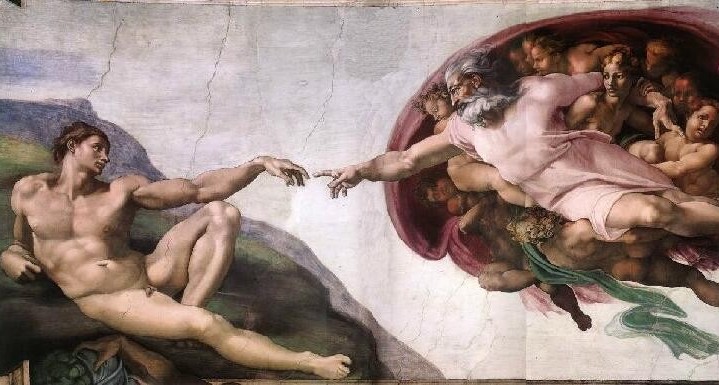

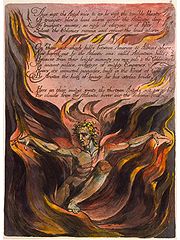

Blake’s “To Annihilate the Self-hood of Deceit,” 1804-1808

Whenever we are tempted to believe that our current economic disparities and injustices are just the way it has to be, Frye in Fearful Symmetry takes on the money economy from a prophetic perspective:

Money to Blake is the cement or cohesive principle of fallen society, and as society consists of tyrants exploiting victims, money can only exist in the two forms of riches and poverty; too much for a few and not enough for the rest. La proprieté, c’est le vol, may be a good epigram, but it is no better than Blake’s definition of money as “the life’s blood of Poor Families,” or his remark that “God made man happy & Rich, but the Subtil made the innocent, Poor.” A money economy is a continuous partial murder of the victim, as poverty keeps many imaginative needs out of reach. Money for those who have it, on the other hand, can belong only to the Selfhood, as it assumes the possibility of happiness through possession, which we have seen is impossible, and hence of being passively or externally stimulated into imagination. An equal distribution, even if practicable, would therefore not affect its status as the root of a evil. Corresponding to the consensus of mediocrities assumed by law and Lockean philosophy, money assumes a dead level of “necessities” (notice the word) as its basis. Art on this theory is high up among the nonessentials; pleasure, in society, tends to collapse very quickly into luxury and affection. (CW 14, 82)

Statue of Paine in Burnham Park, Morristown, New Jersey

Today is Tom Paine‘s birthday (1737-1809). We posted on Paine’s Common Sense earlier this month. But with events in Egypt and Tunisia still unfolding, he deserves another look in order to distinguish between revolutionary ideology and revolutionary imagination — a distinction ultimately between secondary concerns and primary ones.

From Fearful Symmetry:

For Satan is not himself a sinner but a self-righteous prig. As Blake explains: “We do not find any where that Satan is Accused of Sin; he is only accused of Unbelief & thereby drawing Man into Sin that he may accuse him.” As long as God is conceived as a bloodthirsty bully this priggishness takes the form of persecution and heresy-hunting as a service acceptable to him. But we saw that under examination Old Nobodaddy soon vanishes into a mere perpetual-motion machine of causation. And as Deism is an isolation of what is abstract and generalized in Christianity, Satan in Blake’s day has become a Deist, and has turned to subtler forms of persecution, to ridicule and shoulder-shrugging and pointing out contemptuously how little evidence there is for any kind of reality except that of natural law.

Yet Deism professed to be in part a revolutionary force. The American and French revolutions were largely Deist-inspired, and both appeared to Blake to be genuiney imaginative upheavals. He wrote poems warmly sympathizing with both, hoping that they were the beginning of a world-wide revolt that would begin his apocalypse. He met and liked Tom Paine, and respected his honesty as a thinker. Yet Paine could write in the Age of Reason: “I had some turn, and I believe some talent for poetry; but this I rather repressed than encouraged, as leading too much into the field of imagination.” The attitude to life implied by such a remark can have no permanent revolutionary vigour, for underlying it is the weary materialism which asserts that the deader a thing is the more trustworthy it is; that a rock is a solid reality and that the vital spirit of a living man is a rarefied and diaphonous ghost. It is no accident that Paine should say in the same book that God can be revealed only in mechanics, and that a mill is a microcosm of the universe. A revolution based on such ideas is not an awakening in the spirit of man: if it kills a tyrant, it can only replace him with another, as the French Revolution swung from Bourbon to Bonaparte. . . An inadequate mental attitude to liberty can think of it only as a levelling-out. Democracy of this sort is a placid ovine herd of self-satisfied mediocrities. (CW 14, 71-2)

“Whatever you think of WikiLeaks, they have not been charged with a crime, let alone indicted or convicted. Yet look what has happened to them. They have been removed from the Internet … their funds have been frozen … media figures and politicians have called for their assassination and to be labeled a terrorist organization. What is really going on here is a war over control of the Internet, and whether or not the Internet can actually serve its ultimate purpose—which is to allow citizens to band together and democratize the checks on the world’s most powerful factions,” – Glenn Greenwald.

All of this is disturbing. But the most troubling thing about it is the fact that “media figures and politicians” are actually calling for the death of Julian Assange and people associated with him because they are “terrorists.” The situation has quickly become so grotesque that the routine weighing-in of Sarah Palin (idiotically characterizing the leak as a “treasonous” act, even though Assange is Australian and operates out of Europe) is now the least of our worries. After the normalization of torture under the Bush administration, it seems that anything goes.

Rounding out our references today to Fearful Symmetry, here’s Frye reminding us about an aspect of the human condition we complacently tend to overlook:

Tyranny is seldom (in the long run, never) imposed on people from without; it is a projection of their own pusillanimity. Tyranny and mob rule are the same thing. (CW 14, 63)

Or, as Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founders whom Teabaggers like to cite as though they owned the copyright, said at the birth of the American republic: “Those who would sacrifice liberty for security deserve neither.”

The praise and international recognition that Fearful Symmetry brought Frye did not come easily. Frye told David Cayley that the book went through “five complete rewritings of which the third and fourth were half again as long as the published book” (CW 24, 924). He reported the same thing in interviews with Art Cuthbert, Valerie Schatzker, and Andrew Kaufman (ibid. 413, 595, 671). Then there was the major rewriting called for by Carlos Baker, one of the readers for Princeton University Press. Part of Baker’s report on Frye’s 658‑page manuscript can be found in Ian Singer’s introduction to the Collected Works edition of Fearful Symmetry (CW 24, xxxv). Other parts are recorded by John Ayre (Northrop Frye: A Biography (192–3), who has a full account of Baker’s judgments about the strengths and weaknesses of the book. Frye’s response to Princeton was to undertake another rewriting. Once he had completed this large task, Baker reread the report and sent the memorandum below to Datus C. Smith, Jr., the director of Princeton University Press.

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY

Inter‑Office Correspondence

Department of English

To: Datus C. Smith, Jr.

From: Carlos Baker

Subject: MS. of Frye’s Book on Blake

September 10, 1945.

I have reread this MS. with particular interest and care in order to discover just how complete the revision was. I find that he has done the job with great attention and thoroughness.

1) The length is lessened by about 20% with, I should say, a 20% gain in intensity and interest.

2) He has either eliminated or completely reworked all the allusions to other major poems than those of Blake about which I originally felt quarrelsome. What is left seems to me right and just, and his method of handling these matters at the heads of chapters seems to me preferable to the method I suggested: viz. separating them off into one section of the book by themselves.

3) He has been liberal and helpful in inserting signposts of the reader’s self‑orientation. But nota bene: if you decide to print the book, you ought still to insist on a prefatory page where the Blakean canon is listed. Or this could appear as a one‑page appendix.

4) In short the book is now definitely publishable, is the best book of Blake that I know, and I should describe it as brilliant, sensitive, witty, and eminently original. It should do much to make better known and more respected a poet who might have been more so at an earlier date but for a series of accidents of which he himself was one of the most conspicuous.

5) With carefully chosen and strategically placed reproductions of Blake’s own pictures, it should make a handsome book. Both because of the size of the Blake cult and the originality of these utterances, the book might create something of a stir, especially in Academia but also outside.

I find in the revision a crack not there before, anent Blake’s use of Rahab, the Apocalyptic Whore of Babylon. Says Frye slyly: The Joyce of Finnegans Wake might have referred to her as The Last Strumpet or The Great Whorn.

On this date in 1964 Edith Sitwell died (born 1887).

Sitwell provided an enthusiastic review of Fearful Symmetry in the Spectator (10 March 1947) where she observed: “To say it is a magnificent, extraordinary book is to praise it as it should be praised, but in doing so one gives little idea of the huge scope of the book and its fiery understanding.”

Here’s Frye in his letter of thanks to Sitwell on January 7, 1948:

Dear Miss Sitwell:

Ever since I read your review of Fearful Symmetry in the Spectator I have been wanting to write you and wondering what to say. I have finally decided that the best thing to say is thank you. (Denham, Selected Letters, 24-5)

After the jump, a much longer letter to Sitwell written on April 12th of that same year. Headnote and footnotes courtesy of Bob Denham.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rBHDEoBWja0

The sword of Edward III

On this date in 1349 Edward III led the English forces to victory over the French in the Battle of Crécy, one of many battles fought during the Hundred Years’ War through the reigns of four English kings — Edward III, Richard II, Henry IV, and Henry V — and which ultimately ended in English defeat after Joan of Arc appeared on the scene to rally the French in their cause.

Frye on Blake’s “King Edward the Third”:

“King Edward the Third” is an exercise in the idiom of Elizabethan drama, just as the songs are, if more successfully, exercises in the corresponding lyrical idiom. It is a very curious piece. Apparently, if one believes that England has always been the home of democracy and constitutional government, and France — at least until the Revolution — a hotbed of tyranny and superstition, one can also believe that the Hundred Years’ War was a blow struck solely in the interests of progress. The English are famous for transforming their economic and political ambitions into moral principles, and to the naive mercantile jingoism of the eighteenth century, which assumed that freedom of action was the same thing as material expansion, there seemed nothing absurd in thinking that the unchecked growth of England’s power involved the emancipation of the world. At any rate, Akenside, in his Ode to the Country Gentlemen of England, seems to have had a vague idea that war with France is somehow connected with the principles of Freedom, Truth and Reason as well as Glory, and refers to the Hundred Years’ War as a crusade in favor of these principles. Akenside was a Whig; Thomson and Young, who wrote a good deal to the same effect, were also Whigs, the liberals of their time, and it is not really surprising if the young Blake, looking for a historical example of the fight of freedom against tyranny, should have selected the exploits of Edward III. A good deal of the poem is simply “Rule Britannia” in blank verse. . . . (Fearful Symmetry, 179-80)

Giovanni di Paulo, Dante and Beatrice Leaving Heaven, ca. 1465

Responding to Bob Denham’s post

I like and agree with all that you say about Frye and the Bible, Bob, but feel there are a few things missing, like typology and prophecy. To say that Frye is looking at the Bible from the point of view of a literary critic is correct but seems to me to be a far too cold and detached statement–Frye as a scientific anatomist.

In Fearful Symmetry Frye is learning from Blake and teaching us that the Bible is a complete book of vision. With my philosophical and theological frinds I have enjoyed many heated and lively conversations, but we always seem to reach an impass when we come to the word “vision”. Their favorite word is “insight”, the eureka moment, and this seems to be pretty well an established occurrence in consciousness, and the title of a major work by that other great Canadian thinker, Bernard Lonergan. This “insight” is the basis for an alternative to faculty psychology, dealing with the soul and its attributes, which has now been abandoned in the wake of scholasticism. The nearest scholasticism comes to Blake’s “vision” is with the word “emanation”, as in Aquinas’ “intelligible emanations”, our participation through the act of “insight” in the light or mind of God. Understanding is what we achieve each time we have an “insight”. The historian Herbert Butterfield states that the rise of modern science outshines everything since the birth of Christianity. Modern science comes with the Enlightment and philosophers like Paul Ricoeur, Gadamer, Eric Voegelin and Leo Strauss are now trying to dismantle its stranglehold and go beyond it.

In this sense, Frye does not approach the Bible as a scientist or literary critic but, instead, as a prophet and poet. What emerges from Fearful Symmetry is Blake’s universal cry that we find at the opening of his poem Milton: “Would to God that all the Lord’s people were Prophets.” Numbers XI. ch. 29 v.

To go beyond either/or, Frye approaches the Bible both as a literary critic where he suspends value judgements but also as a prophet like Jeremiah where he uses value judgments to tear down and to build up. [See Jean O’Grady’s brilliant article “Re-valuing Value“.] The key to prophecy is typology, the Medieval approach to the Bible, displayed to us splendidly in Dante’s Divine Comedy. In “Paradiso” Canto 6, Justinian is the only speaker, and here we deal with the Law; canto 10, the Circle of the Sun, the Circle of the Sages, we deal with Wisdom; canto 17 deals with Prophecy. His great, great grandfather tells Dante must go back to earth and assume the mantle of the prophet and poet. Armed with the phases of revelation: Law, Wisdom, Prophecy, Etc., Dant must construct for us The Divine Comedy, which is nothing less than a recreation of the Bible.

Frye’s engagement with the Bible brought about a fundamental change in him as it did in Dante, and it was this change into prophet and poet that was necessary before he could present us with his lasting emanation, The Collected Works of Northrop Frye, which we must learn to read as the Bible for our time.

I’ve been mulling over Clayton’s comment about Frye’s antisupernatruralism. There are close to a hundred places in Frye’s writings where he uses the word “supernatural,” but I don’t get the sense from these references that he’s antisupernatural. Most often Frye’s use of “supernatural” does not point to some transcendent religious realm or being. For him, the supernatural is what is fantastic (ghosts, vampires, omens, portents, oracles, magic, witchcraft, and the like) or above nature––as in the heroes of myth in the Anatomy: superior to other people (superhuman) and to their environment (supernatural). The supernatural would include the “children of nature” (“the helpful fairy, the grateful dead man, the wonderful servant who has just the abilities the hero needs in a crisis,” Anatomy 196–7) that we find in folk tales and romances. For Frye the supernatural is not a term that is opposed to unbelief. It’s simply the antithesis of the natural. In his essay on Emily Dickinson he writes, “the supernatural is only the natural disclosed: the charms of the heaven in the bush are superseded by the heaven in the hand.” Sometimes Frye speaks of the supernatural as phenomena that are difficult to explain. He reports on this episode with his mother:

She has always regarded her mind as something passive, worked on by external supernatural forces, and is very unwilling to think that anything might be a creation of her own mind—besides, it flatters her spiritual pride to think of herself as a kind of Armageddon. She told me that once she was working in her kitchen when a voice said to her “Don’t touch the stove!” So she jumped back from it, and something caught her and flung her against the table. Half an hour later the voice came again, “Don’t touch the stove!” She jumped back again and this time was thrown violently on the floor. When Dad came home for dinner he found her with a black eye and a bruised shin. I have read a story by Thomas Mann in which he tells of seeing a similar thing in a spiritualistic séance [the episode involving Ellen Brand toward the end of Mann’s Magic Mountain—the section entitled “Highly Questionable” in chapter 7]: that story was the basis of the priest’s remark to the ghost in my Acta Victoriana sketch: “If you are very lucky, you may get a chance to beat up a medium or two” [“The Ghost”]. Mother has also heard noises like tapping and so on, and was tickled to get hold of a copy of a Reader’s Digest in which a writer describes having gone through exactly similar experiences [Louis E. Bisch, “Am I Losing My Mind?” Reader’s Digest, 27 (November 1935), 10–14.] The best way to deal with mother is, I think, to get her books telling of similar things that have happened to other people: she’s not crazy, but might be excused for thinking she was if she didn’t realize that such things are more common than she imagines. She was delighted with my Acta story, and I’ll try to get her that Mann thing and C.E.M. Joad’s Guide to Modern Thought, which has a chapter on those phenomena. (Frye-Kemp Correspondence, 13 August 1936).

In Fearful Symmetry Frye speaks of the supernatural as the human creative power: “All works of civilization, all the improvements and modifications of the state of nature that man has made, prove that man’s creative power is literally supernatural. It is precisely because man is superior to nature that he is so miserable in a state of nature” (41). Frye’s reaction to natural religion, with its premise of the analogia entis [anology of being], is almost always negative. Both Word and Spirit, he declares in his Late Notebooks, can be used without any sense of the supernatural attached to them.

Here is Clayton Chrusch’s detailed summary of Chapter Five of Fearful Symmetry:

The greater the work of art, the more completely it reveals the gigantic myth which is the vision of this world as God sees it, the outlines of that vision being creation, fall, redemption and apocalypse.

For a Christian, the totality of creative power is called the Word of God or Jesus. This creative power sees a vision of all time and space whose mythic shape is the same as that of the Bible: “creation, fall, redemption and apocalypse.” Frye writes, “all works of art are phases of that archetypal vision,” and the greatest art, such as the Bible, most completely reveals this vision.

Blake viewed the central myth of the Bible as a genuine vision of reality, and his work as aligned with it. This Biblical vision is an imaginative one, however, and Blake dismissed as irrelevant questions of historical veracity. Blake also rejected what he considered stupidly orthodox readings of the Bible of the kind that attempted moral justification of God’s Old Testament bloodthirstiness. Rather he saw such passages as true visions of a false god, and he saw such perverse orthodoxy as Anti-Christ. The Bible, though, is not a unique or exhaustive expression of the Word of God, rather all nations, in Blake’s view, had the same genuineness of vision, though the ancient Greeks in particular obscured and forgot theirs.

In art, the most complete vision is cyclic, and in poetry this complete form is called epic and properly covers “the entire imaginative field from creation to the Last Judgement” though, like the Bible, it is most concerned with the the world’s cyclical movement between the opposite states of falleness and redemption. Non-epic forms can be considered as particular episodes within the universal epic vision. As such, literature, at least Western literature, can be seen as more conventional than is commonly acknowledged.

Blake sees creative actions as an artist’s real life. Actions and thoughts “on the ordinary Generation plane” may have nothing to do with an artist’s creativity. This is why Wordsworth’s preface to the Lyrical Ballads is “twaddle,” while the poems themselves are clear visions, and why in general we cannot trust or limit the meaning of art to the artist’s conscious intention. The real intentions that produce art are often sub- or super-conscious.

Blake held diction to be very important though he makes few statements about it. His position begins, as it usually does, with a rejection of Locke, in particular, he rejected the notion that words are inadequate substitutes for real things. On the contrary, words make things intelligible and therefore more real. The meaning of a word, beyond generalities, is undefinable because it depends both on its context and its relation to human minds. The sounds, rhythms, and associations of a word–attributes that have little to do with its general definition–are functional in poetry and can give a word a meaning that is beyond the capacity of any dictionary to capture.

As for rhyme and meter, Blake insists that “the sound, sense and subject are to make a complete correspondence at all times” which means that fixed stanzaic patterns may be appropriate for short lyrics but rhyme is dropped in the longer works and meter and line length are varied according to the content.

We should understand poetry by unified and immediate perception. We might have to do hard intellectual work in order to unify the poem in our minds, but it is the direct experience that is the meaning of the poem. The intellectual scaffolding that helped us achieve that experience should just fall away. “For,” as Blake writes, “[a poem’s] Reality is its imaginative Form.” The wrong kind of allegory is “merely a set of moral doctrines or historical facts, ornamented to make them easier for simple minds.” The wrong way to read allegorical literature is to reduce it to such a set of abstractions. Great allegorical writing exists, and it is great not because of the quality of ideas it represents but because of the imaginative power of its vision.

We cannot hold to art as good or true because art envisions both good and bad, true and false. Religion does claim sure and reliable knowledge of truth and goodness, but there is something false about this claim. The power of religion lies not in dogma but in the visionary masterpieces that the dogma is derived from. The poet’s task is to go back to the symbols of those masterpieces and to recreate them. The meaning of these symbols (for example, the gods of ancient Greece) becomes more vague over time and the artist’s function is to clarify it.

This is what Blake does. One of his tactics is to use unfamiliar names for his characters. Though he could have called his sky father Zeus, Blake called him Urizen to head off the vagueness that comes with Zeus’s large cloud of associations.

Christianity is not more true than other religions, but its imaginative core, what Frye calls, “its vision of the humanity of God and the divinity of risen Man” is that characteristic imaginative accomplishment of Christianity that “all Christian artists have attempted to recreate.” Even secular writers like Shakespeare and Chaucer are informed by “the universal Word of God, the archetypal vision of ‘All that Exists.'” This vision provides the most profound kind of signficance to all worthwhile art and makes such art allegorical in the sense Dante used when he spoke of anagogy.

Frye writes, “It is the function of art to illuminate the human form of nature.” By this he means that art “interprets nature in human terms.” Only a human being can create a design, but that does not stop art from seeing design in the pattern of a snowflake. Blake’s tiger has a human creator that makes the tiger’s form, which is therefore a human form.