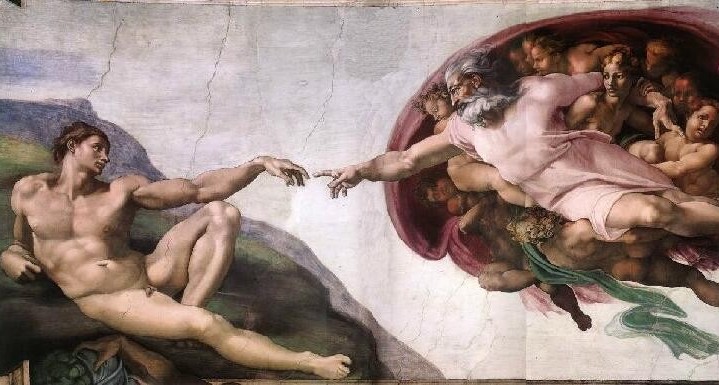

Frye in 1957, the year he published Anatomy of Criticism

Abbate, Gay. “Frye’s Legacy: Scholarship, Loyalty, Humanity: Lighting a Path for Those Who Follow.” University of Toronto Bulletin 4 February 1991: 6–7.

Abley, Mark. “One of Canada’s Foremost Intellectuals Dead at 78.” Whig‑Standard (24 January 1991): 3.

“Anatomising Literature” The Guardian [London and Manchester] (25 January 1991): 39.

Atwood, Margaret. Canadian Literature 129 (Summer 1991): 242–3.

________. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 4–5. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 7.

________. “The Great Communicator.” Globe and Mail (24 January 1991): C1; rpt. in Journal of Canadian Poetry 6 (1991): 1–3.

________. [Tribute]. Brick 40 (1991): 3.

Barber, David. “The Formidable Scholar.” The Whig-Standard Magazine (2 February 1991): 5. [Based on an interview with A.C. Hamilton.]

Barnes, Bart. “Canadian Literary Critic Northrop Frye Dies at 78.” Washington Post (24 January) 1991: D6.

Barilli, Renato. “Frye, corsi e ricorsi della letteratura.” Corriere della Sera (27 January 1991).

Bemrose, John. “The Great Decoder: Northrop Frye Explored Culture’s Myths.” Maclean’s 104 (4 February 1991): 51–2.

Bevington, David. “Northrop Frye.” American Philosophical Society, Proceedings 137, no.1 (March 1993): 125.

Bissell, Claude T. The Independent [London] (26 January 1991): 12. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 10.

________. “Northrop Frye Remembered.” University of Toronto Magazine 18 (Spring 1991): 10.

________. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 8–9.

Brown, Gord. “Norrie’s Wisdom Lives on in His Writings and Students.” the newspaper [University of Toronto] (30 January 1991): 5.

Buckley, Jerome. “Northrop Frye Remembered by His Students.” Journal of Canadian Poetry 6 (1991): 4.

C., G. “Northrop Frye, dalla Bibbia alla civiltà della parola.” La Stampa (25 January 1991).

C., R. “É morto Frye l’innovatore.” La Nazione (25 January 1991).

Chamberlain, Ted. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 9–10. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 11.

Christian Century 108 (20–27 March 1991): 321.

Cook, Eleanor. “Northrop Frye as Colleague.” Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 18.

Cooley, Dennis. “The Educated Imaginer: Northrop Frye (1912–1991). Border Crossings 2 (April 1991): 78.

Cosway, John. “Changes.” The Sunday Sun [Toronto] (27 January 1991): 109.

“Critic Northrop Frye Dead at 78.” Toronto Star (23 January 1991): 28.

Dahlin, Karina. “ U of T Remembers Its Greatest Humanist.” University of Toronto Bulletin (4 February 1991): 1–2.

Denham, Robert D. “Northrop Frye: 1912–1991.” Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly 24 (Spring 1991): 158–9.

Downey, Donn. “Literary Scholar Regarded as Great Cultural Figure.” Globe and Mail (24 January 1991): D6.

Fabiny, Tibor. “Érdekeltség és szabadság” [“Concern and Freedom”]. Nagyvilág (December 1991).

Fisher, Douglas. “A Frydolator Remembers.” Toronto Sun (25 January 1991): 11.

________. “Frye was Right about Quebec.” The Sunday Sun [Toronto] (27 January 1991): C3.

Fletcher, Angus. “In Memoriam. Northrop Frye (1912–1991).” New Vico Studies 9 (1991): 153–4.

Flint, Peter. “Northrop Frye, 78, Literary Critic, Theorist and Educator, Is Dead.” New York Times (25 January 1991): B14.

Foley, Joan. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 6. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 8.

Forst, Graham. “Remembering Norrie, Critic and Teacher.” Vancouver Sun (26 January 1991): D24.

“Frye, Herman Northrop.” Current Biography 52, no. 3 (March 1991): 60.

“Frye’s Genius Recalled in Tributes.” Toronto Star (24 January 1991): D1.

Fulford, Robert. “Frye’s Soaring Cathedral of Thought.” Globe and Mail (26 January 1991): C16.

Garrido-Gallardo, Miguel Angel. “Northrop Frye (1912–1991).” Revista de Literatura 53 (January–June 1991): 175–7.

Globe and Mail (25 January 1991): D8.

Guarini, Ruggero. “Una vita per due gemelle, bellezza e verità. . . .” Il Messaggero (25 January 1991).

Hamilton, A. C. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 10–11. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 11.

________. “Northrop Frye: 1912–1991.” Quill & Quire 57 (March 1991); rpt. in Journal of Canadian Poetry 6 (1991): 5–7.

Harron, Don. “A Memory of Frye.” Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 19.

Hartley, Brian. “Life in the Resurrection: Remembering Northrop Frye.” Herald (March, 1991).

Hoffman, John. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 2. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 4.

Jensen, Bo Green. “Kritikeren, Northrop Frye, 78 †r.” Weekendavisen [Denmark] (1 February 1991).

Johnston, Alexandra F. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 14–15. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 15.

________. “In Memoriam: Chancellor Northrop Frye.” Victoria College Council, Minutes of the Meeting of 11 February 1991. Typescript. 3 pp.

J[ohnson], P[hil]. “A Tribute to Northrop Frye.” Pietisten 6 (April 1991): 5.

Juneau, Pierre. “The Power of Frye’s Words.” The Financial Post (28 January 1991): 8.

________. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 13–14. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 14.

Kenner, Hugh. “Northrop Frye, R I P.” National Review 43 (25 February 1991): 19.

Kushner, Eva. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 12–13. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 13.

Laux, Cameron. The Independent [London] (30 January 1991): 13.

Lee, Alvin. “Northrop Frye: 1912–1991.” The McMaster Courier (12 February 1991): 5.

________. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 11–12. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 12.

Lee, Hope. “Tribute to Northrop Frye.” Presented on the CBC Sunday Morning Program, 27 January 1991. Typescript, 1 p.

“Literary Critic Dies.” Richmond Times-Dispatch (24 January 1991): B2.

“Literary Critic Rode Subway Daily to Work.” Niagara Falls Review (24 January 1991): 7.

Lombardo, Agostino, Baldo Meo, and Piero Boitani. “Il Pagione [A Tribute to Frye].” Broadcast on Italian Radio—RAI, 19 February 1991, at 4:30 p.m.

McBurney, Ward. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 6–7. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 89–9.

McGibbon, Pauline. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 4. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 6.

McIntyre, John P. “Northrop Frye (1912–91).” America 165, no. 1 (6 July 1991): 14–15.

Marchand, Philip. “Frye Really Believed that Literature Could Save Society.” Toronto Star (24 January 1991): D1.

________. “Premier, Friends Pay Tribute to Northrop Frye.” Toronto Star (30 January 1991): E1, E6.

Meo, Baldo. “Northrop Frye e i nuovi furori della critica letteraria.” l’Unita 25 (January 1991): 19.

Miller, Daniel. “Northrop Frye Remembered by U of T.” the newspaper [University of Toronto] (30 January 1991): 10.

Moriz, Andre. “Northrop Frye Tribute Service Draws 800.” The Varsity [University of Toronto] (31 January 1991): 12.

“La morte in Canada di Frye: critica e società.” Il Gazzettino [Venice] (25 January 1991).

“É morto Northrop Frye teorico della letteratura.” Corriere della Sera (25 January 1991).

“É morto il critico Northrop Frye.” Il Giornale (25 January 1991).

“É morto il critico Northrop Frye.” Il Tempo (25 January 1991).

“É morto a Toronto Northrop Frye risalì al ‘profondo’ dell’opera letteraria.” Gazzetta del Sud (25 January 1991).

“Morto critico litterario canadese Northrop Frye.” ANSA News Agency, Rome (24 January 1991).

Mulhallen, Karen. “In Memoriam, Northrop Frye, 1912–1991, R.I.P.” Descant 21–22 (Winter–Spring 1990–91): 7.

Newsweek (4 February 1991): 76.

“Northrop Frye.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch (24 January 1991): 4C.

“Northrop Frye.” The Daily Telegraph (25 January 1991): 19.

O’Malley, Martin. “The Ordinary Side of an Extraordinary Man.” United Church Observer (March 1991): 16.

Nolan, Nicole, and Hilary Williams. “Memorial for Frye.” The Strand [Victoria University] (30 January 1991): 1.

“Northrop Frye.” Times [London] (26 January 1991): 12.

“Northrop Frye 1912–1991.” Toronto Star (1 November 1992): 70.

“Northrop Frye.” Toronto Star (24 January 1991): A26. [Editorial].

Outram, Richard. “In Memory of Northrop Frye.” Globe and Mail (16 February 1991): C16; rpt. in Northrop Frye Newsletter 3, no 2 (Spring 1991): 36.

Pentland, Howard. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 15–17. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 17.

Placido, Beniamino. “É morto Northrop Frye.” La Repubblica (25 January 1991).

Polizoes, Elias. “Northrop Frye’s Legacy Pivotal.” Varsity [University of Toronto] (25 January 1991): 12

Prichard, Robert. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 2–3. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 4.

Rae, Bob. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 3–4. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 5.

Reaney, James. “Northrop Frye: He Educated Our Imagination.” Toronto Star (24 January 1991): A27.

“Remembering Frye.” Globe and Mail (26 January 1991): C10.

Saddlemyer, Ann. University of Toronto Quarterly 61, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 7–8. Appears also in Vic Report 19 (Spring 1991): 9.

Sewell, Gregory. “Literary Critic Northrop Frye Dead.” Varsity [University of Toronto] (25 January 1991): 1.

Stefani, Claudio. “Il molto reverendo Frye.” Il Resto del Carlino (25 January 1991).

Stone, George Winchester. “Herman Northrop Frye (14 July 1912–23 January 1991).” PMLA 106, no. 3 (May 1991): 564, 566.

Stuewe, Paul. “Northrop Frye, 1912–1991.” Books in Canada 20, no. 2 (March 1991): 9.

Teskey, Gordon. “Eulogy of Northrop Frye.” Annual Dinner of the Milton Society, San Francisco, 28 December 1992. Typescript. 4 pp.

Theall, Donald F. “In Memoriam.” Science Fiction Studies 18, no. 2 (July 1991): 288–90.

Thompson, Clive. “Frye First and Foremost a Great Teacher.” The Strand (30 January 1991): 5.

Time (4 February 1991): 61.

Toronto Star (26 January 1991): D7.

Tredell, Nicholas. “Northrop Frye.” PN Review 17 (May–June 1991): 8.

Vega, María José. “La Literatura como Orden: En la muerte de Northrop Frye.” Revista de Extremadura (Segunda época) 9 (September–December 1992): 71–4.

Warkentin, Germaine. “The Loss of Northrop Frye.” http://lists.village.virginia.edu/lists_archive/Humanist/v04/0923.html

Weinbrot, Howard. “On Northrop Frye in Minneapolis, 1990. A Memorial.” Johnsonian News Letter 50 (September & December 1991): 39–5.