I thought this exchange between Russell Perkin and Bob Denham in the Comments section of Bob’s post on the epiphanies was worth bringing forward for more attention.

Perkin:

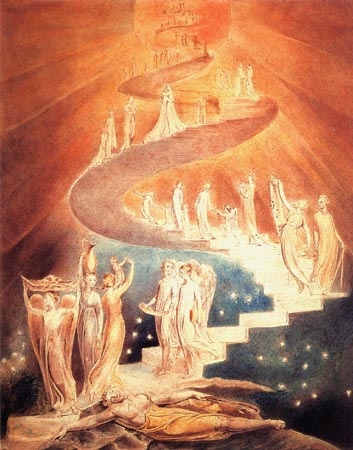

Bob, that’s really interesting stuff! Do you have anything to say about the realization about The Four Zoas that John Ayre describes Frye experiencing “while sitting in the bored husband’s seat in a women’s wear shop on Yonge St. just below Bloor” (p. 177)? Does Frye record this anywhere – Ayre doesn’t give a source. It’s not so much a spiritual vision as a realization about how he had to present Fearful Symmetry. What Ayre calls the “absurdly mundane circumstances” fascinate me. Rather like Francis Thompson seeing Jacob’s ladder pitched between “heaven and Charing Cross”?

Denham:

Russell: I’d forgotten about Ayre’s account of the Four Zoas recognition–Los displacing Orc, it seems to have been. It certainly sounds like one of those momentary flashes of insight and similar to the others. So far as I know, Frye doesn’t mention it elsewhere, but it pretty clearly should be added to the list. Perhaps he recorded something about it in his original Blake notebook, which is not extant.

It would be interesting to know that date of this epiphany. Early 1940s, I’d guess. Frye does have a similar account of Orc-Los business in his 1950 diary: “The tactic of the Blake article is shaping up a little. After I outline his archetypal imagery, which derives from the unfallen world, I go on to archetype of narrative. The archetypal narrative is the heroic quest, which is the Orc cycle. This is in Blake, but he’s not primarily interested in it, as he sees the cyclic shape of it too clearly. That’s the reason for the difficulty in trying to wedge Jungian archetypes, which are all narrative ones, into Blake. The shift over from the Orc cycle to the Los pattern of progressive & redemptive work is really the centre of the problem in [L] [Liberal] that converges on what I call the dialectic development of the conception of the hero. In Blake the cycle of narrative emanating from & returning to the unfallen world is seen so constantly as a simultaneous pattern of significance that the reader has to get this perspective before he can read: it isn’t unfolded to him passively in a narrative sequence.” (Diaries, 431).

Thanks for calling attention to the omission.

As Russell Perkin observes, Frye’s epiphanies concern realizations of solutions to a central or major obstacle in his theorizing, solutions which bring about a sudden crystallization in his thought. They are Eureka moments, mightily magnified versions of what anyone might undergo when they make a breakthrough writing an essay or a book: the sense that everything suddenly comes together, fits together. They are critical or theoretical epiphanies but without ceasing to be spiritual or religious.

I note that the Seattle epiphany about the passage from the oracular to the witty is the subject of the opening paragraphs of the 5th chapter of The Secular Scripture: that moment of reversal at which the lowest point of descent is mysteriously converted into release and ascent to a higher world. The epiphanies, it seems, almost always have to do with Frye’s “great doodle” or mandala-like structure of the mythological/literary cosmos: the sense of everything fitting together is triggered by finding the place, as it were, for an important missing piece in that particularly cryptic jigsaw puzzle. Interestingly, his Seattle epiphany concerning the transition at the southernmost point of the great doodle is, as it were, an epiphany of epiphany, a revelation of revelation–of that moment of “verbal understanding that shakes the mind free”:

As the hero or heroine enters the labyrinthine lower world, the prevailing moods are those of terror or uncritical awe. At a certain point, perhaps when the strain, as the storyteller doubtless hopes, is becoming unbearable, there may be a revolt of the mind, a recovered detachment, the typical expression of which is laughter. The ambiguity of the oracle becomes the ambiguity of wit, something addressed to a verbal understanding that shakes the mind free. This point is also marked by generic changes from the tragic and ironic to the comic and satiric. Thus in Rabelais the huge giants, the search for an oracle, and other lowerworld themes that in different contexts would be frightening or awe-inspiring, are presented as farce. Finnegans Wake in our day also submerges us in a dream world of mysterious oracles, but when we start to read the atmosphere changes, and we find ourselves surrounded by jokes and puns. Centuries earlier, the story was told of how Demeter wandered over the world in fruitless search of her lost daughter Proserpine, and sat lonely and miserable in a shepherd’s hut until the obscene jests and raillery of the servant girl Iambe and the old nurse Baubo finally persuaded her to smile. The Eleusinian mysteries which Demeter established were solemn and awful rites of initiation connected with the renewal of the fertility cycle; but Iambe and Baubo helped to ensure that there would also be comic parodies of them, like Aristophanes’ Frogs. According to Plutarch, those who descended to the gloomy cave of the oracle of Trophonius might, after three days, recover the power of laughter.

In an atmosphere of tragic irony the emphasis is on spellbinding, linked to a steady advance of paralysis or death; in an atmosphere of comedy, we break through this inevitable advance by a device related to the riddle, an explanation of a mystery. . . .

Denham again:

The Secular Scripture provided the final clue in my review of the oracle–to–wit epiphany in Northrop Frye: Religious Visionary. It’s certainly true that Frye’s epiphanies are almost always related to one or more of his diagrammatic, deductive schemes. In the Seattle epiphany the framework seems to be the axis mundi, which Frye would describe many years later in Words with Power as the mountain or ladder archetype. In a letter to Brian Coates (31 March 1971) Frye set down what might be taken as a gloss on the Seattle (oracle to wit) epiphany, where recreation emerges from a demonic descent.

“I think one should keep in mind, when dealing with modern literature, that the mythical map of the universe is much more ambiguous than it was before the Romantic period. For Dante, heaven was up there, hell down there, and consequently all myths of descent were likely to have a sinister or demonic implication. In modern times, the poles of the mythical universe are not heaven and hell, nor are the poles consistently associated with certain spatial projections. The two poles are alienation and identity. In some writers, including Blake and Shelley, the pole of alienation is associated with the sky, and the pole of identity with a submerged world like Atlantis. It is quite possible to have a demonic descent them, as the one in Heart of Darkness or the Waste Land. But it is equally possible to have a journey to the deep interior in search of identity. It is only in this latter case that the theme of rebirth is really built into the mythical structure. The theme of rebirth may of course also be expressed by the theme of eternal recurrence, as it is in Yeats and in Finnegans Wake. And of course recurrence may be looked at in two ways: as an ironic unending cycle or as an image of recreation and the making of all things new. In Finnegans Wake it is unmistakably both; Yeats warbles on the point, partly because he was trying to listen to “instructors” who didn’t know what they were talking about” (Northrop Frye: Selected Letters, 1934–1991, 124).

Perkin again:

Thanks, Bob, and Joe! The date of the women’s wear shop revelation would seem to be 1943, from the context in Ayre’s biography.