Mervyn Nicholson, in the first of what promises to be a series, considers what makes Frye different. In this installment: Desire.

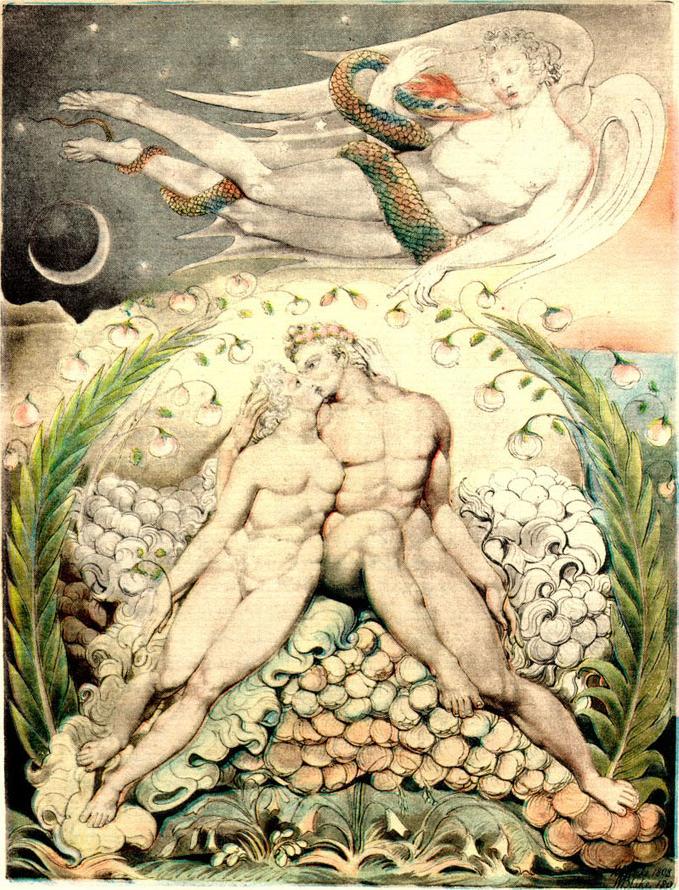

Frye is unusual as a literary-cultural critic-theorist in many, many ways. But one way that I find fascinating is Frye’s attitude toward human desire. Frye was a champion of human desire, as was his mentor, William Blake.

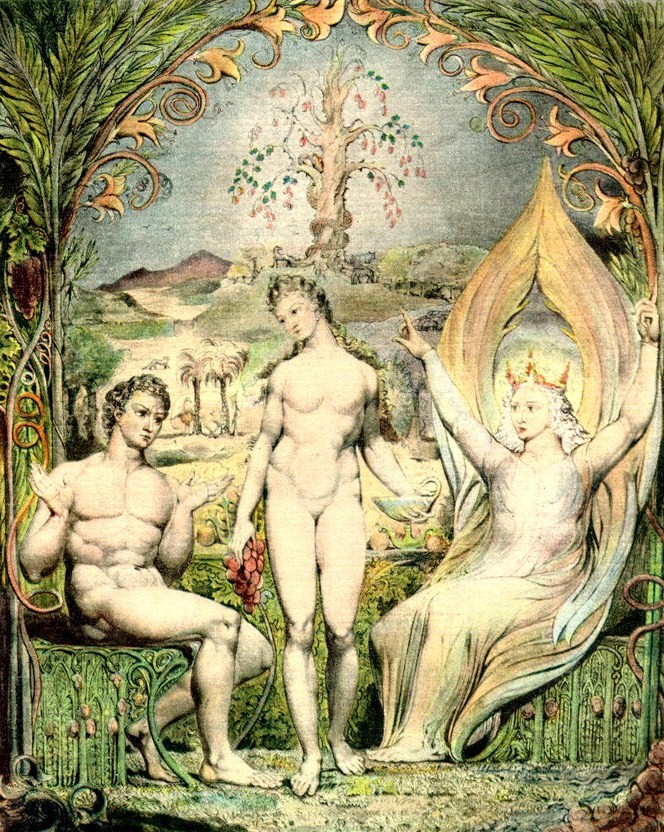

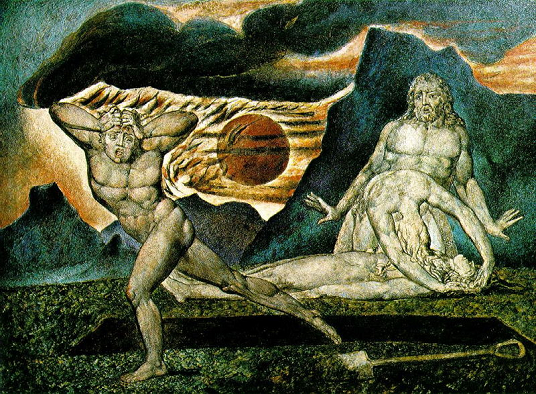

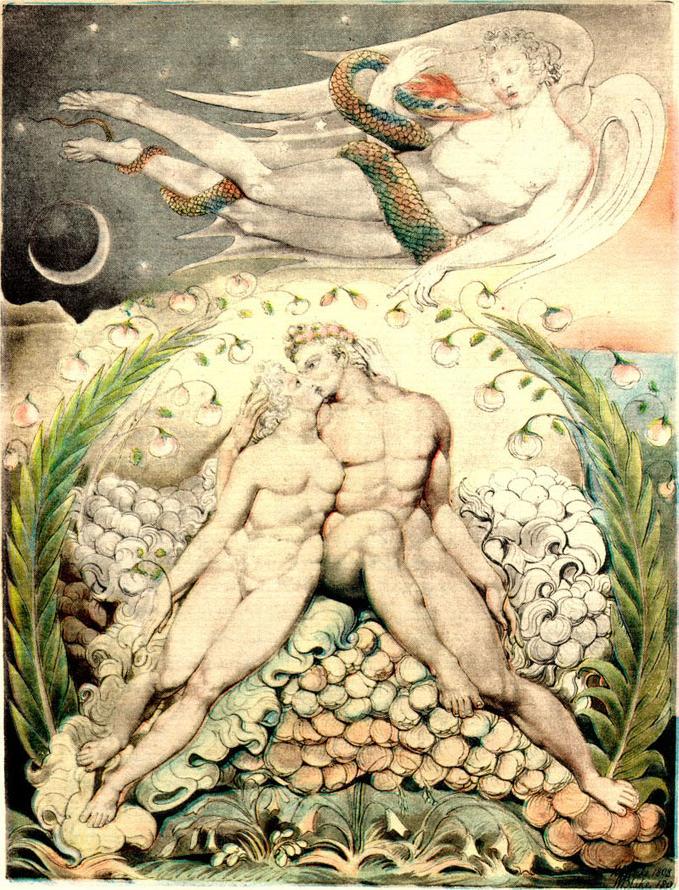

But in this Frye, like Blake, is opposed to practically the entire history of culture, a history of hostility to desire. For Christianity, human desire is corrupted by the Fall, and can not be trusted. What is needed is obedience to authority; by contrast, human desire is in fundamental conflict with the requirements of obedience. The problem began with Adam and Eve who disobeyed, followed desire, and thus brought death into the world along with everything else that is bad, from mosquitoes to forest fires.

Christianity is not alone in distrusting and even disowning human desire. Philosophy has rarely had much respect for desire, which it typically puts somewhere in the basement of human faculties, right next to if not actually in the trash barrel, along with illusion, opinion, prejudice, and other detritus of consciousness. Post-structuralism in its core form of deconstruction maintains the same hostility to desire. Deconstruction as theorized by Jacques Derrida and practiced for example by Paul de Man, has for its keynote a conviction that desire equates with the unreal. An entire attitude is summed up in the dictum of Paul de Man: “Metaphor is error because it feigns to believe in its own referential meaning.” Metaphor and metaphoric thought is indistinguishable from deception, above all self-deception. Political economy—economics—has stressed the dangers of human desire, from at least Thomas Malthus’s Essay on Population on. The standard economics text begins with the premise that “economics is the science of scarcity”: there isn’t enough to go around. In the conflict between what we want and what we can have, necessity always wins. People must keep desire in check, or disaster will result.

Freud, despite his liberal views, is consistent with traditional attitudes. The entire psychoanalytic tradition is deeply mistrustful of desire. What you want but cannot have, you then create imaginary satisfactions for. For example, we fear to die, so we “make up” an afterlife, an imaginary compensation. This view of desire, as the origin of illusion, is fundamental to Freud, who lays it out with particular clarity in The Future of an Illusion. The test of an illusion is whether it is a wish fulfilment. “What is characteristic of illusions is that they are derived from human wishes,” Freud explains. “Thus we call a belief an illusion when a wish-fulfilment is a prominent factor in its motivation . . . the illusion itself sets no store by verification.” Dreams are of course illusory satisfactions, as Freud argues in The Interpretation of Dreams: dreams are all wish-fulfilments. But wish-fulfilments are by definition illusory satisfactions. This is also a theme of the revisionist psychoanalysis of Jacques Lacan, as well as of Melanie Klein and the “object relations” school of psychology. Make-believe compensates for loss and alleviates frustration. But it is still make-believe, and make-believe causes problems. Similarly, Freud insisted that fantasies, conscious and unconscious, cause neurosis—fantasies so endemic in fallible human nature that they begin in infancy. In Freud’s view, infants fantasize pretty weird things because they want weird things, and that weird wanting affects them for the rest of their lives.—our lives, in fact

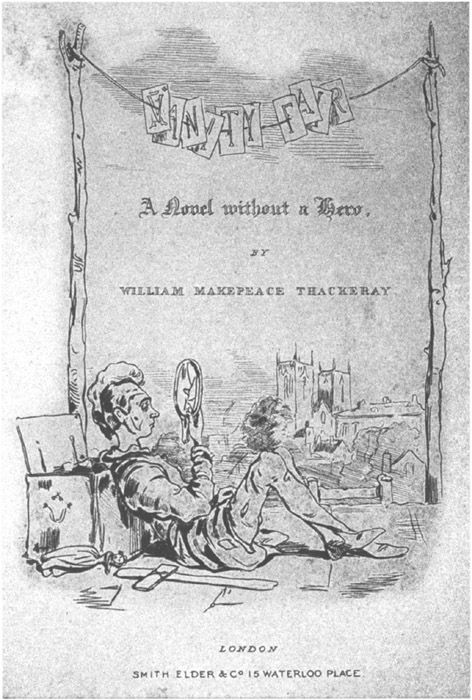

Frye is so different from this tradition! he insists throughout his writing and throughout his career that human desire is good, that it is a guide, that the distinction between what we want and what we do not want — as Frye himself argues in The Educated Imagination — is the basic axis of existence and of civilization itself. Literature is a product of human desire, as is all of civilization. By showing us what we want and what we do not want, literature functions as a guide to ourselves and a means of evaluating the society we have created and that we also have the power to change. For Frye, desire is who we really are.