Re: Merv Nicholson’s “What Makes Frye Different” (1)

I agree that Frye departs from the main traditions of Christian orthodoxy in some significant ways (though how significantly depends on the way one defines those traditions, hardly something on which there is general agreement!) But I think that the idea of original sin is often present in his thought – that is, the idea that human beings are, in Newman’s words, “implicated in some terrible aboriginal calamity.”

Frye identifies the primary concerns, which are our desires for such things as food, shelter, and companionship. But it is only in the imagined world of literature that such concerns are not overwhelmed by the secondary concerns of ideology. And even literary works have their inevitable ideological dimension, as in Frye’s favourite example of Henry V.

Frye sometimes refers to human beings as “psychotic apes”! I think he agrees with Freud that civilization is fragile, doesn’t occur very often, and exists to regulate our desires, which otherwise would be boundless. If there isn’t enough to go around in terms of material goods, how much more is that true in terms of prestige and status.

Freud’s ideas, especially as expressed in Civilization and Its Discontents, seem to me based on a fairly accurate perception about the way that desire has to be controlled and regulated for civilization to exist. And Frye would seem to agree with that in his comments about human beings in society. Somewhere he comments on how the sounds of children at play are far from the pastoral innocence of sentimental imaginings. When he talks about discipline as the way to freedom (as in learning to play the piano), he sometimes sounds like Milton talking about “right reason.”

Thus while Frye rejected what he saw as the neurotic obsessions of some forms of Christianity (e.g., anxieties about drinking alcohol in the tradition in which he was raised), I see him as continuing many of the themes and concerns of Christian humanism.

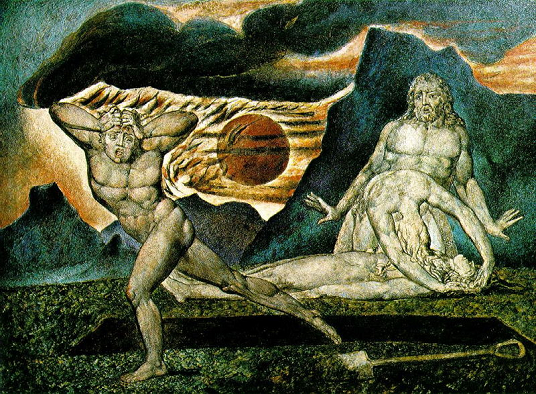

But I readily admit to an inadequate knowledge of Blake, and of the side of Frye which read what Bob Denham refers to as his “kook books,” and I’m sure a much more unorthodox, antinomian Frye exists as well as the figure I am constructing here. I suppose the real question is what one foregrounds in one’s reading of Frye’s work