“Well, the dialectic of belief and vision is the path I have to go down now.” ––Late Notebooks, 1:73

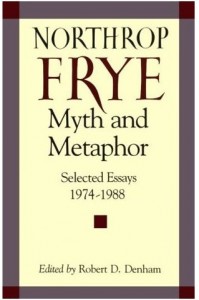

Joe Adamson’s reference earlier today to “The Dialectic of Vision and Belief” reminded me of some notes I made for my students several years back. Page references are to the essay as reprinted in Myth and Metaphor, 93–107. The students were undergraduates, so here and there I provided a bit of background on Hegel, Derrida, McLuhan, et al.

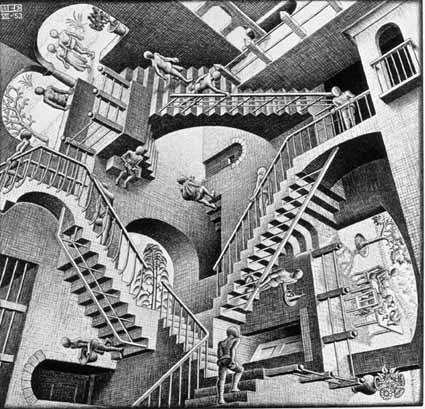

1. Frye calls his title “somewhat forbidding.” We might consider first what dialectic means. The word comes from the Greek dialektos, meaning dialogue or debate. In Plato, dialectic is the science or discipline of drawing rigorous distinctions. In the Middle Ages dialectic was treated in partnership with logic as being one of the trivium in the medieval education system, the other two being grammar and rhetoric. The word dialogue also comes from the Greek root, and this seems to be the sense in which Frye is using the word. Plato wrote his earlier works in dialogue form, using what we now call the Socratic method, which is a way of doing philosophy through discussion between two or more parties. Hegel was the preeminent modern philosopher for Frye (he makes an appearance in this essay on p. 98), and there might be a touch of the Hegelian sense of dialectic in Frye’s title. For Hegel, dialectic refers to the process of overcoming the contradiction between thesis and antithesis by means of a synthesis. So in this essay Frye perhaps means to suggest that something might emerge from the opposition between “belief” and “vision.”

The dialectical method involves the notion that movement, or process, or progress is the result of the conflict of opposites. Traditionally, this dimension of Hegel’s thought has been analyzed in terms of the categories of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Although Hegel tended to avoid these terms, they are helpful in understanding his concept of the dialectic. The thesis, then, might be an idea or a historical movement. Such an idea or movement contains within itself incompleteness that gives rise to opposition, or an antithesis, a conflicting idea or movement. As a result of the conflict a third point of view arises, a synthesis, which overcomes the conflict by reconciling at a higher level the truth contained in both the thesis and antithesis. This synthesis becomes a new thesis that generates another antithesis, giving rise to a new synthesis, and in such a fashion the process of intellectual or historical development is continually generated. Hegel thought that Absolute Spirit itself (which is to say, the sum total of reality) develops in this dialectical fashion toward an ultimate end or goal. For Hegel, therefore, reality is understood as the Absolute unfolding dialectically in a process of self-development. As the Absolute undergoes this development, it manifests itself both in nature and in human history. Nature is Absolute Thought or Being objectifying itself in material form. Finite minds and human history are the process of the Absolute manifesting itself in that which is most kin to itself, namely, spirit or consciousness. In The Phenomenology of Mind Hegel traced the stages of this manifestation from the simplest level of consciousness, through self-consciousness, to the advent of reason.