Responding to Russell’s post earlier today:

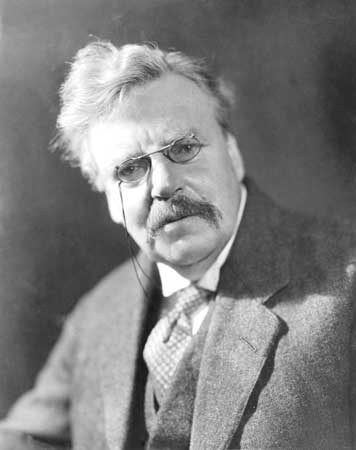

Russell, Frye didn’t write anything extended on Chesterton, so far as I know. He read at least The Victorian Age in Literature and The Everlasting Man when he was a student at Emmanuel College. Here are about three dozen passages in his writings, some of them trivial, that refer to Chesterton.

1. I must expand the conception of dandyism as, essentially, a comic literary convention entering life around the second half of the 19th c. The dandy develops out of the Cléante type of comic moral norm, detached from what is seen as a crowd of preoccupied attached obsessed people, all facing in the same direction. The dandy is essentially conservative, because the facing-one-direction people make an assumption of progress, yet his impact is that of a devil’s advocate, reversing the melodramatic maxims in which society believes. Apart from the French developments, Oscar Wilde popularized the attitude, the progenitor of which in England is really Matthew Arnold, both in his life & in his comedies. An Ideal Husband has the dandy in one of his proper roles—that of gracioso-hero. His attitude is comic-existential, puncturing the balloons of false idealism. A Woman of No Importance has a far more brilliant dandy, but Wilde, partly through an effort to be “fair” to the other side, partly through a streak of masochism, & partly through sheer laziness, completely foozled the conclusion. Anyway, the dandy attitude survives in the early (twenties) essays of Aldous Huxley, whose epigrams are mainly inverted clichés, in Yeats’ association of dandyism & heroism, in Lytton Strachey, & in the contemporary New Yorker—see its Knickerbocker figure and again the inverted melodrama clichés of its cartoons. G.K. Chesterton is an anti-dandy; Shaw uses the dandy formula of course, but never puts much of himself behind it. I think something of this might get into an essay on Samuel Butler, who isn’t a dandy, but uses one as a norm in WAF [The Way of All Flesh], & is in marked contrast to William Morris, who’s a tough little Cockney drudge, to use Carlyle’s opposite term. (Notebooks for “Anatomy of Criticism,” CW 23, 265)