Following Joe’s critique of Alter, I too went back to Alter’s essay “Northrop Frye between Archetype and Typology.” I’ll begin with the conclusion to Joe’s post, where he writes that “Alter simply wants nothing to do with the imaginative element, with metaphor or myth in the Bible, or if it must be admitted, since it is everywhere, only as a kind of rhetorical ornamentation that is easily hedged in by a crabbed and mean-spirited descriptivism.” I agree that Alter wants to distance himself from Frye’s way of reading the Bible – for reasons that I will get to later – but I find in his work a powerful response to the imaginative element in the Bible. It’s just that for Alter this element exhibits itself in difference rather than identity, and in particulars rather than typological categories. Alter ends his essay by saying that “The revelatory power of the literary imagination manifests itself in the intricate weave of details of each individual text.” Going back to Joe’s conclusion, I would also dispute the adjectives “crabbed and mean-spirited”; Alter reads the Bible as a work of great literature, a revelation of what it means to be human, and an exploration of the way that human lives are embedded in history. I regard Alter as a major humanist critic, not someone I would put on the same level as Frye, but certainly a literary scholar and critic whom I find in many ways exemplary.

To reiterate a point I made in an earlier post, when teaching the Bible and literature I set up a dialectic between the approaches of Alter and Frye. For me, both are necessary. In looking at Milton, or aspects of Shakespeare, Frye’s visionary-typological approach is a powerful way of seeing what these poets have done imaginatively with the Bible. On the other hand, in discussing the novel, which in the English tradition at least is profoundly grounded in the Bible, Alter’s commentaries on the Hebrew Bible are an invaluable resource, as of course they are in considering the literary qualities of the Hebrew Bible itself. Not only do the two critics have divergent ways of reading, but for pedagogical purposes it is useful that one of them writes out of a Christian tradition and the other from a Jewish tradition.

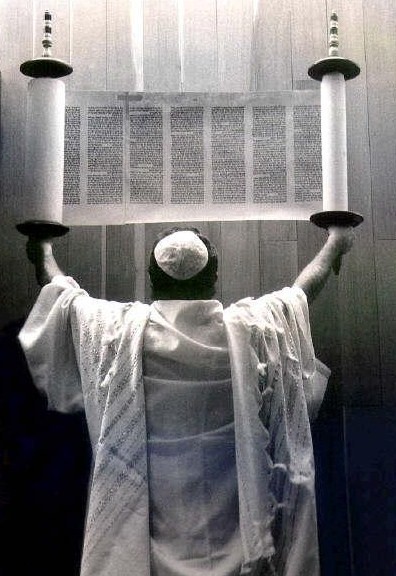

I have a vivid memory of Alter’s paper at the Frye and the Word conference: for me it had the kind of lucid authority that makes you feel you are in the presence of an exceptional scholar. (You can see him lecturing for yourself here.) That conference took place as I was getting ready to teach my course on the Bible and Literature for the first time, and I was therefore especially attentive when Alan Mendelsohn, in his introduction to Alter’s lecture, praised Alter’s translation of the book of Genesis for opening up dramatically new perspectives on that text. In teaching the course, I have found Mendelsohn’s recommendation to be exactly right: Alter’s commentary reveals countless complexities and subtleties in the text of the Hebrew Bible, which with his knowledge of the European literary tradition he is often able to relate to later literary developments. (He has since translated the two books of Samuel, the whole of the Torah, and the Psalms.) I was even inspired by reading these commentaries to start learning Hebrew, in spite of the fact that I am not very adept with foreign languages. Thus through the long hot summer of 2006, I spent several hours a week sitting down with a handful of undergraduates less than half my age, under the guidance of Wendell Eisener, a religious studies professor at Saint Mary’s who most kindly let me sit in on his class. I would not claim to be a Hebrew scholar as a result, but I learned enough to start to see how the language works and to be able to use reference tools.

Joe points out some of Alter’s negative language towards Frye, and I think that this language indicates a certain degree of anxiety. At least twice, Alter uses the word “beguiling” to characterize Frye’s method of reading the Bible. This word now has the primary meaning of “charming,” or “diverting attention in a pleasant way,” but it also retains the sense embodied in the root guile of “deluding, entangling with guile.” Alter is clearly aware of, and wary of, the seductive power of Frye’s way of reading the Bible, which he notes is not merely a practice of worldly criticism but something that includes “a certain homiletic touch.” And Alter does acknowledge that the mythological way of reading exemplified by The Great Code is an appropriate description of the way that many poets in the Christian tradition have read the Bible.