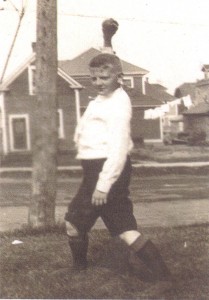

Frye clutching a baseball in front of the family's Pine Street home, Moncton, N.B. ca. 1922.

Further to Russell Perkin’s earlier post:

As for Frye‑reading sports fans, I spent the first couple of decades of my life doing nothing but playing basketball, and a love of that game, along with tennis and handball, still runs deep.

I suspect Frye was not much given to sports because competition was too much rooted in the competitive instinct, though he does report that his first memories have to do with World War I and the game of shooting Germans. Anticipating Stephen Dedalus, he also says that early on he was given to “staying out of games because of danger of breaking glasses.” And then there is the violent aspect of competitive sports. Jack Megill, a character in Frye’s unfinished novel, describes “a scrubby little soccer game where the football was about the only one on the field that wasn’t kicked.” In a cryptic little “proverb from hell” on the topic of violence, he writes, “Sadism in sports: gladiators to hockey.”

Is part of it something in the Canadian psyche? Frye told one of his U.S. classes “that students conditioned from infancy to be part of a world power are bound to be very different in their attitude from students conditioned from infancy to watching the game from the sidelines and seeing more of the game perhaps than the participants.”

But if there’s a game at the center (“centre” for you maple‑leafers) of Frye’s world, it’s got to be chess, which is largely an archetype of the Eros vision, but there are games in each of the quadrants of his HEAP scheme: “the game of athletic contest (the epic game) has its tonic in Adonis, the game of fate (cards) in Hermes, the game of chance (dice, divination) in Prometheus, & the game of strategy (chess & board games) in Eros.” This comes from The “Third Book” Notebooks, where the game of chess is very much on Frye’s mind. Otherwise, from here and there in the corpus, this sampler:

COMPENSATORY REACTION

The writing kids produced a very pleasant story by Catharine Card, who is a really sweet girl. Darcy Green tells me that her shyness actually is neurotic & she’s been under psychiatric treatment. It’s a women’s magazine formula, but very nicely done. Gloria Thompson did a parody of My Last Duchess. I find having all that beauty & charm & health & youth in my office a bit overpowering: I find, not unnaturally, that I want to show off. I never worked that out of my system because, not being athletic, I couldn’t show off in the approved ways during the mating season. (Diaries, 28 February 1950)

SHAKESPEARE FOR FOOTBALLERS

I’ve been reading a long & tiresome book by somebody in New York University—Holzknecht—on what he calls the “backgrounds” of Shakespeare’s plays [Karl Julius Holzknecht, The Backgrounds of Shakespeare’s Plays]. It’s a useful compilation of Shakesperean scholarship, but he has no critical ability whatever—for some reason there seems to be a quite sharp cleavage between scholarship & criticism in the study of Shakespeare. The mark of the earnest & unimaginative teacher is over it: he rides the “healthy & normal” stuff to death, &, as his introduction makes clear, is writing for a lumbering hawbuck of an undergraduate who’d much rather play football. So his chapter on Shakespeare’s English, which is otherwise quite good, hasn’t a syllable about the important & extensive subject of Shakespeare’s bawdy. (Diaries, 1 August 1950)

SLEEPY FOOTBALLERS

My two-hour graduate group was completely bad: I’d prepared nothing for it, & just filled in repeating myself [the course was “The Methods and Techniques of Allegory”]. It would have been all right if they’d wakened up & asked a few questions, but they were as sleepy as a bunch of frosh after a seven o’clock football game, and did nothing. (Diaries, 11 January 1952)

COOPERSTOWN

This morning we started out again across a highway that wound through the valleys of the Catskills, though there was one point where we could have seen five states, according to the sign, if there hadn’t been a heavy mist. The country is full of tourist resorts for foreign-born people, and have curious things, like swimming pools beside the road. Around noon we hit Cooperstown, the home of the baseball. . . . We approached the baseball museum and peeked through the window, but the admission was 80 cents and none of us could have distinguished Babe Ruth’s balls from his bat at seven paces, so we thought the hell with it. (Diaries, 15 April 1952)

CARPET BALL

The United Church Carpet Ball League worshipped with us. That’s a game for older men, an interesting-looking group of lower-middle class types. Evidently they bowl or something on a carpet—anyway it’s not a reading group, to judge from their president, who acted as clerk & struggled with Isaiah. (Diaries, 1 March 1953)

SUNDAY SPORTS

I plumped for May Birchard for alderman again, but she still didn’t make it, though she was close. The Sunday sport issue went pro [a plebiscite on whether to legalize Sunday sports, an issue that was on the ballot with the Toronto municipal elections]. Those in favour of permitting sports events on Sunday won by a small margin. For NF’s unsigned, greatly to my surprise. Both Protestants & the Cardinal had gone against it, two of the three papers who had been for it had ratted midway (the third, the Star, was against it anyway) and not a candidate except Lamport had dared to open his mouth in favor if it. It indicates that “public opinion” that everyone is afraid of is largely a matter of lobbying and organized minorities.

[Frye editorialized on this for the Canadian Forum, 29 February 1950]:

A plebiscite on the legalizing of Sunday sports was the most controversial and highly publicized issue in the recent municipal elections in Toronto, and the results have a significance not confined to that city. The Protestant churches seemed to take the issue as a test case of their social influence, and brought all the pressure they could to persuade their flocks to vote “no.” Cardinal McGuigan also came out on the “no” side. Two Toronto papers which seemed inclined to support the question promptly went “no” too (the third one, the Star, remained firm in its conviction that the Toronto Sunday should never be profaned by anything more secular than the Toronto Star Weekly). Hardly a single candidate for office, except one controller who had more or less stuck his neck out on the subject, dared to say that he was anything but unalterably opposed to Sunday sport. In addition, the wording of the proposal was so loaded as to make it, if not impossible, at least illogical, for many voters to vote for it and in accordance with their consciences as well. Nothing remained but to roll up a thumping “no” majority. The vote went the other way. The “yes” majority was not large, but considering the circumstances it amounted to a decisive rejection of clerical advice on the part of the electorate.

This result tends to confirm the general correctness of Professor Hart’s thesis in relation to Windsor, where the Sunday sport question went “yes” by a two-to-one vote. A modern industrial town tends to become increasingly secularized and to find its social and moral sanctions in, say, the labour hall rather than in the churches. But this is not the whole story. Toronto municipal voters are largely a middle-class tax-paying group, and it is extremely unlikely that all or even the great majority of “yes” voters were entirely outside all Christian communions. If the vote means anything, it surely means something like this: people are increasingly unable to believe in the disinterestedness of the churches, or in their ability to distinguish a moral issue from one that merely appears to threaten their social and economic position. That the churches are spending far too much of their energies in an inglorious rearguard action against the incidental vices of society; that they cannot distinguish cause from effect in social evil; that they have not only tended to retreat into the propertied middle class, but are no longer coming to grips with the real needs even of that class. This is clearly the attitude, or something like the attitude, implied in the Toronto vote. It may be utterly wrong; but an institution committed to humility and self-examination cannot afford to underestimate or disregard the good faith of its critics.]

ST. THOMAS : ART : : FRYE : BASKETBALL PLAYOFFS

At Princeton I bought four books to keep me up to date with the mid-50s: Maritain’s, Malraux’s Voices of Silence, Auerbach’s Mimesis, and Curtius on medieval literature and Latin. At that time Curtius was the only one I could read with any real profit: Mimesis was all very well but I was working out an anti-mimetic theory of literature; Malraux said a few excellent things but was full of bullshit; Maritain, as I said, kept busting his skull against this preposterous “Art and Scholasticism” thesis, insisting that critical theory just had to come out of St. Thomas, who cared as much about the arts as I do about basketball league playoffs. (Late Notebooks, 1:244)

WHAT’S WRONG WITH THIS PICTURE?

The phrase “mass culture” conveys emotional overtones of passivity: it suggests someone eating peanuts at a baseball game, and thereby contrasting himself to someone eating canapés at the opening of a sculpture exhibition. The trouble with this picture is that the former is probably part of a better educated audience, in the sense that he is likely to know more about baseball than his counterpart knows about sculpture. Hence his attitude to his chosen area of culture may well be the more active of the two. (The Modern Century, 20)