In response to “Thoreau, Frye, and Same-Sex Desire“:

There’s this from Frye’s 1949 diary:

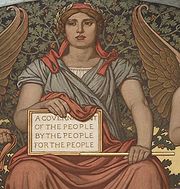

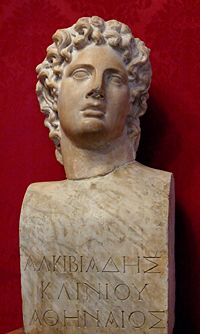

University lecturing is not teaching but a form of intellectualized preaching. You can go into all the world and preach the gospel, but if you try to teach any more than about twelve disciples you’ve had it. Teaching relates two individuals through Socratic love, which has to be homosexual. I can’t really teach a woman, because, being a woman, the things organic to her learning process are female, and shut me out. All I could do would be to identify myself with her animus, which puts me, as I’ve discovered and elsewhere remarked, in a hell of a spot. To teach a boy is to form his character, which means partly to unite him to the males of the tribe. It also involves the sort of love which sees with complete clarity what the boy’s character is: you can’t, that is, teach a frivolous person in the way you would teach a preternaturally solemn one. I’m not a teacher according to this line of thought; and I wonder if it’s possible without some physical interest in men, or sublimation of it. Even Jesus had a beloved disciple, as Marlowe pointed out. I can trace no such interest in myself.

The Marlowe reference: “That St John the Evangelist was bed-fellow to Christ and leaned always in his bosom; and that he used him as the sinners of Sodoma” (Richard Baines, “A Note Concerning the Opinion of One Christopher Marlowe, Concerning His Damnable Judgment of Religion and the Scorn of God’s Word,” Christopher Marlowe, Complete Poems and Plays [London: Dent, 1976], 513). The so-called “Baines’s Note” is a series of opinions on religion, said to have been Marlowe’s but apparently penned by Baines in an effort to bring Marlowe before the Court of the Star Chamber.

And these two passages from the Late Notebooks:

Tillich on the miserable reality of the concrete churches: when I went to church in Montreal with Lorna that jackass disrupted the whole feeling of the service by braying about homosexuals. Before the service, I met a woman I’d never seen before who pecked out of me in two minutes the fact that I had no earned doctorate. Malice, like other pacts with the devil, certainly gives one preternatural perceptions, up to a point.

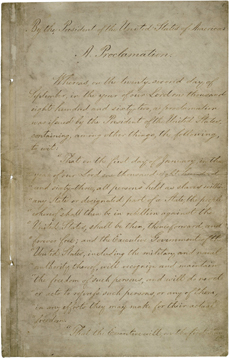

Eros Regained starts with the homosexual refined Jesus lying on the bosom of a male beloved disciple, trying to get away from his mother but still so hung up sexually that he insisted his father was not his father and that his mother was a virgin, rescuing a bride symbolically but saying “don’t touch me” as his last words to a woman. [The notion of the homosexual or androgynous Jesus is repeated here and there in Frye’s writings––scores of times.]