Thank you for the comments, Ed. Characteristically, Thoreau had as little time for Lincoln as he had for anyone who compromised on the issue of slavery: on the day of Lincoln’s inauguration, in the company of his old friend Bronson Alcott, according to Walter Harding’s great biography, he “announced himself as ‘impatient with politicians, the state of the country, the State itself, and with statesmen generally.’ He roundly accused the Republican Party of duplicity and called Alcott to account for his favorable opinion of the new administration” (Harding 444).

Thoreau was a difficult friend, highly demanding in intellectual, moral, and spiritual terms, though he won from many, like Alcott, an intense loyalty. Not surprisingly, his “Plea for Captain for John Brown” is even more uncompromising than Emerson in the way he defends and exalts Brown.

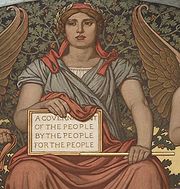

Some of Lincoln’s writings, like the Gettysburg address, do indeed, as you put it so well, Ed, “attain the level of kerygmatic intensity, spiritual proclamation.” I always try to include some of Lincoln’s writings in my American literature course as a great example of the oratorical power reached by great leaders, like Churchill, at particular historical moments.

Frye mentions Lincoln in Anatomy as an example of “the rhetoric of non-literary prose”:

The most concentrated examples of this are to be found in the pamphlet or speech that catches the rhythm of history, that seizes on a crucial event or phase of action, interprets it, articulates the emotions concerned with it, or in some means employs a verbal structure to insulate and conduct the current of history. Areopagitica, Johnson’s letter to Chesterfield, some sermons in the period between Latimer and the Commonwealth, some of Burke‘s speeches, Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, Vanzetti’s death speech, Churchill’s 1940 speeches, are a few examples that come readily to mind.

The measured cadences of these historical oracles represent a kind of strategic withdrawal from action: they marshal and review the ranks of familiar but deeply-held ideas. (327)

I also found this brief passage by Frye in The Critical Path, which seems relevant to your comments:

Certainly there is a tremendous radical force in American culture, in Whitman’s Democratic Vistas, in Thoreau’s Walden and Civil Disobedience, in Jefferson’s view of local self-determination, in Lincoln’s conception of the Civil War as a revolution against the inner spirit of slavery, which could give a very different social slant to the American myth of concern [as opposed, Frye mean, to other myths of concern in the “Old World”]. Ezra Pound, for all his crankiness, was trying to portray something of this innate radicalism in his John Adams Cantos. There is also of course a right wing that would like to make the American way of life a closed myth, but its prospects at the moment do not seem bright. (95)

God knows that Frye had no illusions about what he called the whirligig of history, but this last sentence–written forty years ago–has a sad and ironic ring to it today, at a time when even someone like Obama and the best initiatives of American democrats are so thoroughly hedged in by an loud and ignorant populism, phony Boston tea parties, and the apparently unthinking majority belief in a neo-conservative ideology that identifies freedom with the license to exploit and oppress, and to enrich oneself at the expense of everyone else, most particularly the poor and most vulnerable.

We might also call attention to Frye’s concluding paragraph to the Whidden Lectures, delivered at McMaster University on the occasion of the centenary of Confederation:

I referred earlier to Grove’s A Search for America, where the narrator keeps looking for the genuine America buried underneath the America of hustling capitalism which occupies the same place. This buried America is an ideal that emerges in Thoreau, Whitman, and the personality of Lincoln. All nations have such a buried or uncreated ideal, the lost world of the lamb and the child, and no nation has been more preoccupied with it than Canada. The painting of Tom Thomson and Emily Carr, and later of Riopelle and Borduas, is an exploring, probing painting, tearing apart the physical world to see what lies beyond or through it. Canadian literature even at its most articulate, in the poetry of Pratt, with its sense of the corruption at the heart of achievement, or of Nelligan with its sense of unfulfilled clarity, a reach exceeding the grasp, or in the puzzled and indignant novels of Grove, seems constantly to be trying to understand something that eludes it, frustrated by a sense that there is something to be found that has not been found, something to be heard that the world is too noisy to let us hear. One of the derivations proposed for the word “Canada” is a Portuguese phrase meaning “nobody here.” The etymology of the word “Utopia” is very similar, and perhaps the real Canada is an ideal with nobody in it. The Canada to which we really do owe loyalty is the Canada that we have failed to create. In a year bound to be full of discussions of our identity, I should like to suggest that our identity, like the real identity of all nations, is the one that we have failed to achieve. It is expressed in our culture, but not attained in our life, just as Blake’s new Jerusalem to be built in England’s green and pleasant land is no less a genuine ideal for not having been built there. What there is left of the Canadian nation may well be destroyed by the kind of sectarian bickering which is so much more interesting to many people than genuine human life. But, as we enter a second century contemplating a world where power and success express themselves so much in stentorian lying, hypnotized leadership, and panic-stricken suppression of freedom and criticism, the uncreated identity of Canada may be after all not so bad a heritage to take with us. (The Modern Century)

Yes, thanks for this, Bob. And even more powerful perhaps in its evocation of the pastoral myth and its relation to both America’s and Canada’s “buried or uncreated ideal, the lost world of the lamb and the child” is the passage from the Conclusion to the Literary History of Canada, where he speaks of Edward Hick’s great painting of The Peacable Kingdom.

“Here, in the background, is a treaty between the Indians the the Quaker settlers under Penn. In the foreground is a group of animals, lions, tigers, bears, oxen, illustrating the rophecy of Isaiah about the recovery of innocence in nature [11:6-9]. Like the animals of the Douanier Rousseau, they stare past us with a serenity that transcends conscousness. It is a pictorial emblem of what Grove’s narrator was trying to find under the surface of America: the reconciliation of man with man and of man with nature: the mood of Thoreau’s Walden retreat. of Emily Dickinson’s garden, of Huckleberry Finn’s raft, of the elegies of Whitman. . . . This mood is closer to the haunting vision of a serenity that is both human and natural which we habe been struggling to identify in the Canadian tradition. It we had to characterize a distinctive emphasis in that tradition, we might call it a quest fo the peacable kingdom” (CW 12: 371)