Thank you for the comments, Ed. Characteristically, Thoreau had as little time for Lincoln as he had for anyone who compromised on the issue of slavery: on the day of Lincoln’s inauguration, in the company of his old friend Bronson Alcott, according to Walter Harding’s great biography, he “announced himself as ‘impatient with politicians, the state of the country, the State itself, and with statesmen generally.’ He roundly accused the Republican Party of duplicity and called Alcott to account for his favorable opinion of the new administration” (Harding 444).

Thoreau was a difficult friend, highly demanding in intellectual, moral, and spiritual terms, though he won from many, like Alcott, an intense loyalty. Not surprisingly, his “Plea for Captain for John Brown” is even more uncompromising than Emerson in the way he defends and exalts Brown.

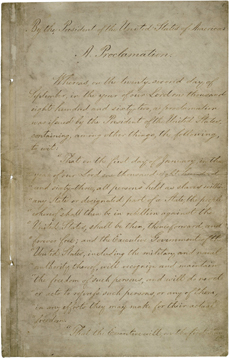

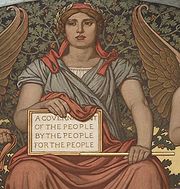

Some of Lincoln’s writings, like the Gettysburg address, do indeed, as you put it so well, Ed, “attain the level of kerygmatic intensity, spiritual proclamation.” I always try to include some of Lincoln’s writings in my American literature course as a great example of the oratorical power reached by great leaders, like Churchill, at particular historical moments.

Frye mentions Lincoln in Anatomy as an example of “the rhetoric of non-literary prose”:

The most concentrated examples of this are to be found in the pamphlet or speech that catches the rhythm of history, that seizes on a crucial event or phase of action, interprets it, articulates the emotions concerned with it, or in some means employs a verbal structure to insulate and conduct the current of history. Areopagitica, Johnson’s letter to Chesterfield, some sermons in the period between Latimer and the Commonwealth, some of Burke‘s speeches, Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, Vanzetti’s death speech, Churchill’s 1940 speeches, are a few examples that come readily to mind.

The measured cadences of these historical oracles represent a kind of strategic withdrawal from action: they marshal and review the ranks of familiar but deeply-held ideas. (327)

I also found this brief passage by Frye in The Critical Path, which seems relevant to your comments:

Certainly there is a tremendous radical force in American culture, in Whitman’s Democratic Vistas, in Thoreau’s Walden and Civil Disobedience, in Jefferson’s view of local self-determination, in Lincoln’s conception of the Civil War as a revolution against the inner spirit of slavery, which could give a very different social slant to the American myth of concern [as opposed, Frye mean, to other myths of concern in the “Old World”]. Ezra Pound, for all his crankiness, was trying to portray something of this innate radicalism in his John Adams Cantos. There is also of course a right wing that would like to make the American way of life a closed myth, but its prospects at the moment do not seem bright. (95)

God knows that Frye had no illusions about what he called the whirligig of history, but this last sentence–written forty years ago–has a sad and ironic ring to it today, at a time when even someone like Obama and the best initiatives of American democrats are so thoroughly hedged in by an loud and ignorant populism, phony Boston tea parties, and the apparently unthinking majority belief in a neo-conservative ideology that identifies freedom with the license to exploit and oppress, and to enrich oneself at the expense of everyone else, most particularly the poor and most vulnerable.